Diplomatic Bluebook 2023

Chapter 3

Japan's Foreign Policy to Promote National and Global Interests

2 Japan-U.S. Security Arrangements

(1) Overview of Japan-U.S. Security Relationship

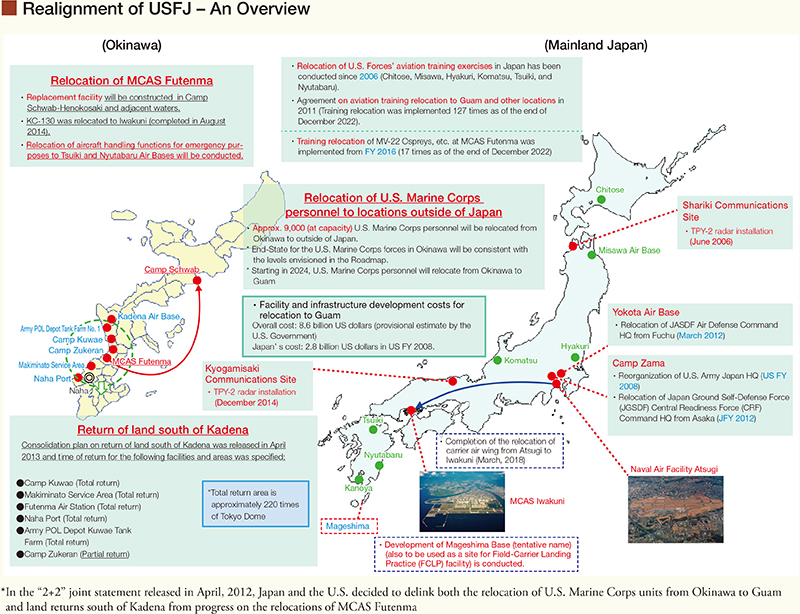

Under the security environment surrounding Japan, which is becoming increasingly severe at an ever more rapid pace, it is indispensable to strengthen the Japan-U.S. Security Arrangements and to enhance the deterrence and response capabilities of the Japan-U.S. Alliance not only for the peace and security of Japan, but also for the peace and stability of the Indo-Pacific region. Japan and the U.S. are further enhancing their deterrence and response capabilities under the Guidelines for Japan-U.S. Defense Cooperation (“The Guidelines”) and the Legislation for Peace and Security. Through such efforts, Japan and the U.S. have been expanding and strengthening cooperation in a wide range of areas, including missile defense, cyberspace, space and maritime security. While advancing these efforts, Japan and the U.S. have concurrently been working closely on the realignment of U.S. Forces in Japan, including the relocation of Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) Futenma and of approximately 9,000 U.S. Marine Corps in Okinawa to Guam and other locations in order to mitigate the impact on local communities, including Okinawa.

(2) Japan-U.S. Security and Defense Cooperation in Various Fields

A An Overview of Japan-U.S. Security and Defense Cooperation

The Guidelines for Japan-U.S. Defense Cooperation, which were formulated in 2015, reviewed and updated the general framework and policy direction of Japan-U.S. defense cooperation. Through the Alliance Coordination Mechanism (ACM) and other efforts established under these Guidelines, Japan and the U.S. have been sharing information closely, establishing a common understanding of the situation, and engaging in “seamless” responses and efforts from peacetime to contingencies. From its inauguration till now, the Biden administration has consistently made it clear that it places great importance on the Japan- U.S. Alliance.

In January, the Japan-U.S. “2+2” was convened virtually for the first time. The meeting was attended by Foreign Minister HAYASHI Yoshimasa and Defense Minister KISHI Nobuo from the Japanese side, and Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin from the U.S. side. The four Ministers engaged in candid and important discussions on how to advance the evolution of the Japan-U.S. Alliance and continue to effectively address current and future challenges. The outcome of the meeting is broadly summarized in the following three points. Firstly, the Ministers affirmed their commitment to a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP).” They also held an in-depth discussion and aligned their understanding on the changing strategic environment in the region, including China's efforts to undermine the rules-based order and North Korea's nuclear and missile activities. Secondly, they affirmed that they would advance concrete discussions toward fundamentally enhancing the Alliance's deterrence and response capabilities. Furthermore, they concurred on pursuing investments to ensure that the Alliance will maintain its competitive edge into the future, including in the field of space, cyberspace as well as emerging technologies. Thirdly, they concurred on the importance of steadily implementing the realignment of U.S. Forces in Japan and sharing information in a timely manner, from the perspective of mitigating the impact on local communities including Okinawa while maintaining the deterrence of the Japan-U.S. Alliance.

Japan-U.S. “2+2” (January 2023, Washington D.C., U.S.)

Japan-U.S. “2+2” (January 2023, Washington D.C., U.S.)In January 2023, the Japan-U.S. “2+2” was convened in Washington D.C., in a timely manner, immediately after the release of strategic documents by the two countries. The meeting was attended by Foreign Minister Hayashi and Defense Minister HAMADA Yasukazu from the Japanese side, and Secretary of State Blinken and Secretary of Defense Austin from the U.S. side. The two sides welcomed the release of their respective National Security Strategies and National Defense Strategies, and confirmed unprecedented alignment of their vision, priorities, and goals. The following are the three broad outcomes of the meeting. Firstly, Japan and the U.S. carefully aligned their perception of the regional strategic environment, including the greatest strategic challenge of China's foreign policy-based actions aimed at reshaping the international order for its own benefit, North Korea's unprecedented number of ballistic missile launches, and Russia's aggression against Ukraine. Secondly, the two sides affirmed future initiatives toward strengthening the deterrence and response capabilities of the Japan-U.S. Alliance amidst an increasingly severe security environment. Japan welcomed the U.S' determination to optimize its force posture in the Indo-Pacific region including Japan, and the two sides decided to continue close consultation on ways to further optimize U.S. force posture in Japan, including the readjustment of plans for the realignment of U.S. Forces in Japan. They also took time to have in-depth discussions on extended deterrence1 at the ministerial level as one of the agenda, and reaffirmed the strong commitment of the U.S. to the defense of Japan, backed by its full range of capabilities, including nuclear. Furthermore, the two sides also affirmed that attacks to, from, or within space, in certain circumstances, could lead to the invocation of Article V of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty. Thirdly, they reaffirmed the importance of efforts to mitigate the impact on local communities, including Okinawa, and Foreign Minister Hayashi reiterated the request to the U.S. side for safe operation of the U.S. Forces with utmost consideration to the impact on local communities, appropriate responses to incidents and accidents including sharing information in a timely manner, and cooperation on environmental issues. On top of that, in the Japan-U.S. Summit Meeting held in the same month, President Biden reiterated his unwavering commitment to the defense of Japan. The two leaders also welcomed the national security strategies of the two countries are aligned with each other and renewed their determination to further strengthen the deterrence and response capabilities of the Japan-U.S. Alliance, including seeking to create synergies in the implementation of the strategies. In addition, they instructed to further deepen concrete consultations regarding Japan-U.S. cooperation on the security front, taking into account the discussions at the Japan-U.S. “2+2.”

In 2022, Japan continued to engage in personnel exchanges with senior U.S. defense officials, including successive visits to Japan by Frank Kendall III, Secretary of the Air Force in August, General David H. Berger, Commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps and Charles A. Flynn, Commanding General, U.S. Army, Pacific in September, Admiral John C. Aquilino, Commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command in October, and Lt Gen. William M. Jurney, Commander, U.S. Marine Corps Forces, Pacific and Commanding General Fleet Marine Force, Pacific in December. In April, Foreign Minister Hayashi accepted an invitation from the U.S. to visit the USS Abraham Lincoln together with Ambassador of the U.S. to Japan, Rahm Emanuel. In addition, the Japan-U.S. Extended Deterrence Dialogue was held in the U.S. in June and Tokyo in November. This Dialogue was established in 2010, and as a part of Japan-U.S. security and defense cooperation, it provides an opportunity for the two governments to discuss regional security, Alliance defense posture, nuclear and missile defense policy, and arms control issues, to engage in an in-depth exchange of views on means to sustain and strengthen extended deterrence, which is at the core of the Japan-U.S. Alliance and to deepen mutual understanding on alliance deterrence. As a part of this Dialogue, participants visited the Ohio-class submarine USS Maryland in June, and observed the “KEEN SWORD 23” Japan-US Bilateral Joint Exercise in November. Through such multilayered initiatives, Japan will continue to promote security and defense cooperation with the U.S., and to further strengthen the deterrence and response capabilities of the Alliance.

- 1 Providing deterrence that a country possesses to its allies and others.

B Missile Defense

Japan has been making steady efforts to develop and engage in the production of the Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) system while continuing cooperation with the U.S., including on the steady implementation of joint development and joint production of the Standard Missile 3 (SM-3 Block IIA) since 2006, and Japan is fully prepared to protect the lives and property of its citizens from the threat of ballistic missiles to Japan under any circumstances. Japan is also advancing efforts to effectively address new aerial threats, including hypersonic weapons. At the Japan-U.S. “2+2” held in January 2023, based on the progress of joint analysis on counter-hypersonic technology, the Ministers concurred to begin joint research on important elements including advanced materials and hypersonic testbeds, and also concurred to begin discussion on potential joint development of a future interceptor.

C Cyberspace

At the Japan-U.S. “2+2” meeting convened in January 2023, Japan and the U.S. concurred to intensify collaboration to counter increasingly sophisticated and persistent cyber threats. In light of the necessity for cross-governmental efforts by both Japan and the U.S., stakeholders from both sides engage in discussions, through frameworks such as the Japan-U.S. Cyber Dialogue, on bilateral cooperation across a wide range of areas. The two sides are continuing to cooperate on matters related to cyberspace, promoting bilateral policy coordination, strengthening systems and capabilities, and exchanging incident information, while taking into consideration Japan's cyber security strategy and the cyber policies of the U.S.

D Space

At the Japan-U.S. “2+2” convened in January 2023, Japan and the U.S. committed to deepening cooperation on space capabilities, and considered that attacks to, from, or within space, present a clear challenge to the security of the Alliance, and affirmed such attacks, in certain circumstances, could lead to the invocation of Article V of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty. At the Japan-U.S. Summit Meeting held in the same month, the two sides concurred on further promoting Japan-U.S. cooperation in the area of space. Japan and the U.S. are continuing to cooperate on space security, including through mutual exchanges of information in the field of Space Situational Awareness and others, as well as cooperation on hosted payloads (mission instruments loaded onto other entities' satellites).

E Information Security

Information security plays a crucial role in advancing cooperation within the context of the alliance. Based on this perspective, both countries continue to hold discussions designed to enhance their cooperation regarding information security, the importance of which was affirmed in the Japan-U.S Summit Meeting held in May 2023 and the Japan-U.S. “2+2” held in January 2023.

(3) Realignment of U.S. Forces in Japan

While steadily advancing the efforts described above, the Government of Japan will continue to make every effort to mitigate the impact on local communities, including Okinawa, by soundly promoting the realignment of U.S. Forces in Japan, including the relocation of MCAS Futenma to Henoko.

Similarly in the Joint Statement of the Security Consultative Committee (“2+2”) released in January 2022, the two sides confirmed the importance of accelerating bilateral work on these force realignment efforts. At the Japan-U.S. “2+2” held in January 2023, Japan and the U.S. affirmed the need to optimize the Alliance force posture based on the improved operational concepts and enhanced capabilities, including the defense of the Southwestern Islands of Japan. They also confirmed that the forward posture of U.S. forces in Japan should be upgraded to strengthen Alliance deterrence and response capabilities by positioning more versatile, resilient, and mobile forces with increased intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, anti-ship, and transportation capabilities. In line with such policy, Japan and the U.S. affirmed that the Japan-U.S. Roadmap for Realignment Implementation, as adjusted at the Japan-U.S. “2+2” in April 2012, will be readjusted so that the 3rd Marine Division Headquarters and the 12th Marine Regiment will remain in Okinawa and the 12th Marine Regiment will be reorganized into the 12th Marine Littoral Regiment by 2025. This effort will be carried out while maintaining the basic tenets of the 2012 Realignment Plan, with utmost consideration to the impacts on local communities. Japan and the U.S. also confirmed the importance of accelerating bilateral work on U.S. force realignment efforts, including construction of relocation facilities and land returns in Okinawa, and the relocation of Marine Corps personnel from Okinawa to Guam beginning in 2024.

In particular, the return of lands in Okinawa has been realized by completing various return projects based on the April 2013 “Consolidation Plan for Facilities and Areas in Okinawa,” even after the return of a major portion of the Northern Training Area (NTA, approximately 4,000 hectares) in December 2017. The return of all areas indicated as “Immediate Return” under the Consolidation Plan was achieved with the return of a portion of the Facilities and Engineering Compound in Camp Zukeran in March 2020. The land near Samashita Gate at Futenma Air Station was also returned in December 2020, followed by the return of the laundry factory area of Makiminato Service Area (land along National Route No. 58) in May 2021. In May 2022, which marked the 50th anniversary of the reversion of Okinawa to Japan, Japan and the U.S. concurred to enable the public use of the Lower Plaza Housing Area of Camp Zukeran as a greenspace, ahead of its return to Japan. The necessary preparations are underway toward the start of use in FY2023.

(4) Host Nation Support (HNS)

With a view to ensuring the effective operations of U.S. Forces in Japan amidst the growing severity of the security situation surrounding Japan, Japan bears a part of costs, such as the costs of Facility Improvement Programs (FIP), within the scope provided for under the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA). In addition, Japan has also borne the labor costs for U.S. Forces working in Japan, utilities costs, and training relocation costs, by concluding the Special Measures Agreements (SMAs) which sets out special measures relating to the SOFA. Under the New SMA signed on January 7 and entered into force on April 1, it was decided that Japan will also bear the expenditures related to the procurement of training equipment and materials which will contribute, not only to the readiness of U.S. Forces in Japan but also to the enhancement of the interoperability between the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) and the U.S. Forces. Based on the SOFA and the New SMA, the Government of Japan will bear the HNS costs from FY2022 to FY2026.

In consultations on the New SMAs, as both parties concurred that the costs borne by Japan should be used to build a foundation upon which the Japan-U.S. Alliance will be further strengthened, the Japanese side decided to refer to this budget by a Japanese phrase that points to its goal of enhancing Alliance readiness and resiliency.

During the effective period of the new SMAs (April 1, 2022 to March 31, 2027), the annual average budget for HNS is approximately 211 billion Japanese yen.

(5) Various Issues Related to the Presence of the U.S. Forces in Japan

To ensure the smooth and effective operation of the Japan-U.S. security arrangements and the stable presence of U.S. Forces in Japan as the linchpin of these arrangements, it is important to mitigate the impact of U.S. Forces' activities on residents living in the vicinity and to gain their understanding and support regarding the presence of U.S. Forces. The Government of Japan has been making utmost efforts to make improvements in specific issues in light of the requests from local communities. Among these issues are preventing and responding to incidents and accidents involving U.S. Forces, abating the noise by U.S. Forces' aircraft, and dealing with environmental issues at U.S. Forces' facilities and areas, including the sound implementation of the Agreement on Cooperation in the Field of Environmental Stewardship of 2015 and the Agreement on Cooperation with regard to Implementation Practices relating to the Civilian Component of the United States Armed Forces in Japan of 2017. For example, when the leakage of water containing substances such as Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) occurred as a result of the spill of fire-fighting foam, at the Naval Air Facility Atsugi due to heavy rains in September, Japanese officials accessed the facility based on the Supplemental Agreement on Environmental Stewardship to conduct a site visit. Japan and the U.S. are also cooperating closely in the field of health and hygiene issues including infectious diseases such as the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). On January 28, the Quarantine Procedure Panel under the Japan-U.S. Joint Committee was reorganized and upgraded to the new “Quarantine and Health Protection Subcommittee (QHS)” which the health authorities of both Japan and the U.S. participate in. Japan and the U.S. will continue to further strengthen cooperation to put in place thorough measures to prevent the spread of infectious diseases, and to mitigate the anxiety among the local communities.

The “TOFU: Think of Okinawa's Future in the U.S.” program provides an opportunity for high school and university students from Okinawa to witness for themselves what Japan's alliance partner, the U.S., is truly like, and the role that Japan plays in the international community, as well as to promote mutual understanding between the two countries. Due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, this program was implemented as a Tokyo Dispatch Program2 in March 2021. Meanwhile, the Project to Promote Exchanges and Enhance Mutual Understanding Between Japan and the United States, which has been implemented in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA) from FY 2020 to facilitate cultural and educational exchanges between Japanese and American middle and high school students, was organized on a larger scale in FY 2022 (see the Column on page 204).

- 2 Participants from Okinawa are invited to Tokyo to meet related persons involved in Japan-U.S. relations and experts active in the international community (including online meetings), as well as visit and tour various facilities.

(6) The United Nations Forces and U.S. Forces in Japan

Coincident with the start of the Korean War in June 1950, the UN forces was established in July of the same year based on the recommendation of UN Security Council resolution 83 in June. Following the ceasefire agreement concluded in July 1953, the United Nations Command (UNC) Headquarters was relocated to Seoul, South Korea in July 1957, and UNC-Rear (UNC-R) was established in Japan. Established at Yokota Air Base, UNC-R currently has four military staff members including a stationed commander, as well as military attachés from nine countries who are stationed at embassies in Tokyo as liaison officers for the UN forces. Based on Article 5 of the Agreement Regarding the Status of the United Nations Forces in Japan, the UN forces in Japan may use the U.S. Forces' facilities and areas in Japan to the minimum extent required to provide support for military logistics for the UN forces. At present, the UN forces in Japan are authorized to use the following seven facilities: Camp Zama, U.S. Fleet Activities, Yokosuka, U.S. Fleet Activities, Sasebo, Yokota Air Base, Kadena Air Base, MCAS Futenma and White Beach Area.

In July 2019, a joint board was held between the Government of Japan and UNC. The meetings saw discussions held over the situation on the Korean Peninsula, with the two sides reaching an agreement on notification procedures in case of unusual occurrences related to the UN forces in Japan. The Government of Japan will continue to work closely with the UN forces.

Since 2020, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA), has conducted exchange programs for the children of U.S. Forces personnel and local junior and high school students in communities that host U.S. Forces Japan. This program aims to nurture human resources who will take an active role in the international society as well as to increase mutual understanding between Japanese and American junior and senior high school students through cultural and educational exchanges.

In 2022, the program was held at Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni (Yamaguchi Prefecture), Camp Kuwae (Camp Lester) (Okinawa Prefecture), U.S. Fleet Activities Sasebo (Nagasaki Prefecture), Misawa Air Base (Aomori Prefecture), and Camp Zama (Kanagawa Prefecture). This column introduces the voices of both Japanese and U.S. students who participated in the program at Camp Kuwae in Okinawa Prefecture.

●Yuina Pope, Lester Middle School

I am glad I was selected to participate in this exchange program. Even though the exchange students had little trouble communicating verbally, I realized that language might not be the only barrier to break down. This experience helped me learn the small cultural differences that I did not notice before. In the beginning, the way we communicated was like through a wall. However, the more time I spent with my groupmates, the more I started to see that we could be friends instead of diplomats. This short time will forever impact my perspective.

●CHINEN Ami, Junior High School Attached to Faculty Education, Ryukyu University

I participated in this program on October 1 and 2, where I engaged in exchanges with students from Lester Middle School located in the air base. At the exchanges, in order to learn about the characteristics of our mutual cultures, we split up into four groups, each comprising junior high school students from Japan and the U.S., and worked to produce short plays and local character mascots featuring the characteristics of each country. In one of the short plays, the actor entered a rest room in Japan and, upon seeing too many buttons, became confused about which one to push to flush the toilet. This was a surprise to me. In addition, the tour of the American school made me realize the significant differences from Japanese ones. For example, the library was about four times larger than the one in our school, there were many sofas of various styles where students could relax, and there were rooms where students could make things with 3D printers, theater rooms, and others. I felt that both Japan and the U.S. have many of their own good points. I hope that this opportunity will bring about more exchanges between students of Japan and the U.S. in the future, and that we can incorporate the good aspects of our respective cultures for exchange programs that promote mutual understanding.

Parliamentary Vice-Minister for Foreign Affairs YOSHIKAWA Yuumi, and Ginowan Mayor MATSUGAWA Masanori, interacting with students (October 2, Ginowan City, Okinawa Prefecture)

Parliamentary Vice-Minister for Foreign Affairs YOSHIKAWA Yuumi, and Ginowan Mayor MATSUGAWA Masanori, interacting with students (October 2, Ginowan City, Okinawa Prefecture) Students giving a group presentation (October 2, Ginowan City, Okinawa Prefecture)

Students giving a group presentation (October 2, Ginowan City, Okinawa Prefecture)