Diplomatic Bluebook 2021

Chapter 4

Japan Strengthening Its Presence in the International Community

2 Japan-U.S. Security Arrangements

(1) Overview of Japan-U.S. Security Relationship

Under the security environment surrounding Japan, which is becoming increasingly severe and uncertain at a remarkably rapid pace, it is indispensable to strengthen the Japan-U.S. Security Arrangements and to enhance the deterrence of the Japan-U.S. Alliance not only for the peace and security of Japan, but also for the peace and stability of the Indo-Pacific region. The year 2020 was a milestone year that marked the 60th anniversary of the signing and entering into force of the current Japan-U.S. Security Treaty (see the Special Feature page on 217), and the Japan-U.S. Alliance has become more solid than ever. Japan and the U.S. are further enhancing their deterrence and response capabilities under the Guidelines and the Legislation for Peace and Security. Through such efforts, Japan and the U.S. have been expanding and strengthening cooperation in a wide range of areas, including ballistic missiles defense, cyberspace, space and maritime security. Japan and the U.S. have been working closely on the realignment of U.S. Forces in Japan, including the relocation of Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) Futenma and of approximately 9,000 U.S. Marine Corps in Okinawa to Guam and other locations in order to mitigate the impact on local communities, including Okinawa, while maintaining the deterrence capabilities of the U.S. Forces in Japan.

Prime Minister Kishi and President Eisenhower at the signing ceremony of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty (January 19, 1960, Washington D.C., U.S.; Photo: Jiji)

Prime Minister Kishi and President Eisenhower at the signing ceremony of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty (January 19, 1960, Washington D.C., U.S.; Photo: Jiji)On January 19, 1960, then-Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke signed the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security Between Japan and the United States of America (Japan-U.S. Security Treaty) at the U.S. White House. The Treaty was signed by U.S. Secretary of State Christian A. Herter for the U.S, and by Prime Minister Kishi himself for Japan. In his memoir, Prime Minister Kishi explained that the revision of the security treaty was the policy of the greatest importance for his Cabinet, and because he took full responsibility for the result, he thought it was only natural that he would be the one to sign it.

The Japan-U.S. Alliance, based on the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty, which was signed with such strong will, remains to be the foundation of Japan's diplomacy and security, despite the great changes of the security environment surrounding Japan. The year 2020 marks the 60th anniversary of the signing and entering into force of this Treaty.

Logo commemorating the 60th anniversary of the signing and entering into force of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty (Image: U.S. Embassy in Japan)

Logo commemorating the 60th anniversary of the signing and entering into force of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty (Image: U.S. Embassy in Japan)On January 17, Foreign Minister Motegi, Defense Minister Kono Taro, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, and U.S. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper issued a joint statement on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the signing of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty. In the Joint Statement, the four ministers paid tribute to their “predecessors for their wisdom, courage, and vision” and expressed their gratitude “to the men and women of the United States Armed Forces and Japan Self-Defense Forces for their dedicated service in protecting [our] common values and interests.” In addition, they reiterated their “unshakeable commitment to strengthen the Alliance and to uphold [our] common values and principles towards the future” while “honoring the achievements of the past 60 years.”

On January 19, exactly 60 years since the signing of the Treaty, a reception to Commemorate the Sixtieth Anniversary of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty was held, co-hosted by the Minister for Foreign Affairs and the Minister of Defense. Among the guests from the U.S. were Ms. Mary Jean Eisenhower, granddaughter of President Dwight Eisenhower, who was President at the time of the signing and entering into force of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty.

President Trump sent a congratulatory message for the reception praising that “the rock-solid Alliance between the two great nations has been essential to peace, security, and prosperity for the United States, Japan, the Indo-Pacific region, and the entire world over the past six decades.”

Prime Minister Abe with Ms. Mary Jean Eisenhower, granddaughter of President Dwight Eisenhower (front row, fourth from the left), at the Reception to Commemorate the Sixtieth Anniversary of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty (January 19, Tokyo)

Prime Minister Abe with Ms. Mary Jean Eisenhower, granddaughter of President Dwight Eisenhower (front row, fourth from the left), at the Reception to Commemorate the Sixtieth Anniversary of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty (January 19, Tokyo)In his speech, Prime Minister Abe looked back on how his grandfather, Prime Minister Kishi, and President Eisenhower deepened their friendship through golf, took up the challenge of the security treaty revision, and eventually brought it to fruition. He addressed, “Let us keep and enhance the U.S.-Japan Alliance, while making it even more steadfast, shall we not, to make it a pillar safeguarding freedom, liberty, democracy, human rights and the rule of law, one that sustains the whole world, sixty years, one hundred years down the road” and stated “Our alliance being one of hope, it is for us to let the rays of hope keep shining even more.”

Today, 60 years since the signing and entering into force of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty, the Japan-U.S. Alliance is stronger, broader, and more vital than ever before. This is the result of the steady and tireless efforts of both Japan and the U.S. over the past 60 years. Going forward, we will further strengthen the Alliance and contribute to the peace, stability and prosperity not only of Japan and the U.S., but also of the Indo-Pacific and the international community.

(2) Japan-U.S. Security and Defense Cooperation in Various Fields

A Efforts Under the Guidelines for Japan-U.S. Defense Cooperation

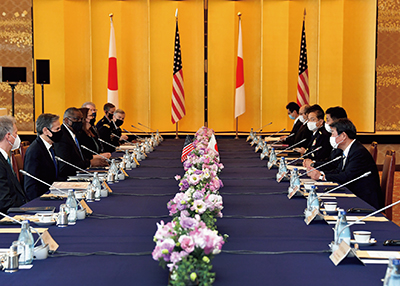

The Guidelines for Japan-U.S. Defense Cooperation, which were announced at the April 2015 meeting of the Japan-U.S. Security Consultative Committee (“2+2”), reviewed and updated the general framework and policy direction of Japan-U.S. defense cooperation. Through the Alliance Coordination Mechanism (ACM) established under these Guidelines, Japan and the U.S. have shared information closely, established a common understanding of the situation, and provided “seamless” responses from peacetime to contingencies. In the “2+2” meeting held in April 2019, four cabinet-level officials from Japan and the U.S. concurred that the Japan-U.S. Alliance serves as the cornerstone of peace, security and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region and that Japan and the U.S. will work together to realize a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP),” and to strengthen cooperation in cross-domain operations such as improving capabilities in non-conventional domains that include space, cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum. They also affirmed that cyberattacks could, in certain circumstances constitute armed attacks, for the purposes of Article 5 of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty. In March 2021, just two months after the inauguration of the Biden administration, Antony Blinken, Secretary of State, and Lloyd Austin, Secretary of Defense, visited Japan in the first overseas trip made by cabinet members under the Biden administration, and held a “2+2” meeting with Foreign Minister Motegi and Defense Minister Kishi Nobuo. The four ministers reaffirmed that the Japan-U.S. Alliance remains the cornerstone of peace, security and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region, and renewed the unwavering commitment of both countries to the Japan-U.S. Alliance. They also concurred to further deepen the coordination to strengthen the deterrence and response capabilities of the Japan-U.S. Alliance. Furthermore, the U.S. underscored its unwavering commitment to the defense of Japan through the full range of its capabilities, including nuclear. The four ministers affirmed that ArticleV of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty applies to the Senkaku Islands and affirmedthat both nations oppose any unilateral action that seeks to undermine Japan's administration of these islands. The four ministers instructed their respective offices to advance concrete works to strengthen the Alliance. They concurred to hold another “2+2” meeting later this year to confirm their outcomes.

The first Japan-U.S. “2+2” meeting convened under the Biden administration (March 16, 2021, Tokyo)

The first Japan-U.S. “2+2” meeting convened under the Biden administration (March 16, 2021, Tokyo)In the second half of 2020, in-person visits by senior defense officials of the U.S. continued to take place in spite of the severe environment under the circumstances of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. In August, General John Raymond, Chief of Space Operations of the U.S. Space Force paid a courtesy call to the Prime Minister as the first foreign high ranking official to do so since the outbreak of COVID-19. In October, Kenneth Braithwaite, Secretary of the Navy, Ryan McCarthy, Secretary of the Army, and Admiral Philip Davidson, Commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, visited Japan successively. These were followed by a visit by General David Berger, Commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps, in November In addition, Japan-U.S. bilateral security discussions were held by way of a video teleconference in October, during which both sides confirmed continued close coordination to maintain a free and open Indo-Pacific, enhance response and deterrence capability, and strengthen the Japan-US Alliance, which is stronger than ever. Through these multilayered efforts, Japan will continue to promote security and defense cooperation with the U.S., further enhancing the deterrence and response capabilities of the Alliance.

B Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD)

Japan has been making steady efforts to develop and engage in the production of the BMD system while continuing cooperation with the U.S., including on the steady implementation of joint development and joint production of the Standard Missile 3 (SM-3 Block IIA) since 2006, and Japan is fully prepared to protect the lives and property of its citizens from the threat of ballistic missiles to Japan under any circumstances. With regard to the ground-deployed Aegis system (Aegis Ashore) that the Cabinet decided to introduce in 2017, the Ministry of Defense announced the suspension of its deployment process in June 2020. As a result of reviews conducted within the Government, the Cabinet reached a decision in December to build two new vessels equipped with the Aegis system in place of the Aegis Ashore system.

C Cyberspace

Based on the necessity for cross-government efforts by both Japan and the U.S., participants from both sides held a follow-up discussion on matters including the outcome of the seventh Japan-U.S. Cyber Dialogue held in October 2019. They also engaged in wide-ranging discussions on Japan-U.S. cooperation in cyberspace, including awareness about the situations, cyber countermeasures in both countries, cooperation in the international arena, and support for capacity building.

D Space

Japan and the U.S. have held discussions on a wide range of cooperation on space through events such as the Seventh Meeting of the Japan-U.S. Comprehensive Dialogue on Space, held in August. Japan and the U.S. are continuing to cooperate on space security, including through mutual exchanges of information in the field of Space Situational Awareness (SSA) and others, as well as concrete examinations of cooperation over hosted payloads (mission instruments loaded onto other entities' satellites). In December, the Governments of Japan and the U.S. exchanged Notes concerning cooperation on hosted payloads, including the loading of U.S. Space Situational Awareness (SSA) sensors onto Japanese Quasi-Zenith Satellite “Michibiki,” (QZS)-6 and QZS-7, scheduled to commence operations in FY2023.

E Multilateral Cooperation

Japan and the U.S. place importance on security and defense cooperation with allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific region. At the Second Japan-Australia-India-U.S. Foreign Ministers' Meeting in October, in order to promote a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific,” which is becoming increasingly important in view of the post-COVID-19 world in a concrete way, the four ministers shared the importance of further developing practical cooperation in various areas such as quality infrastructure, maritime security, counter-terrorism, cyber security, humanitarian assistance/disaster relief, education and human resource development, and broadening cooperation with more countries for the realization of a FOIP.

F Information Security

Information security plays a crucial role in advancing cooperation within the context of the alliance. Based on this perspective, both countries continue to hold discussions designed to enhance their cooperation regarding information security.

G Maritime Security

In forums such as the East Asia Summit (EAS) and the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), Japan and the U.S. stress the importance of peacefully resolving maritime issues in accordance with international law as reflected in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The Guidelines announced in April 2015 also provide that Japan and the U.S. will cooperate closely with each other on measures to maintain maritime order in accordance with international law, including the freedom of navigation. Even under the conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Japan and the U.S. continued to conduct joint exercises in the surrounding waters in the region including the South China Sea. Furthermore, cooperation with regional partners including Australia and India was strengthened through exercises such as MALABAR (Japan-U.S.-Australia-India joint exercise) and Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC).

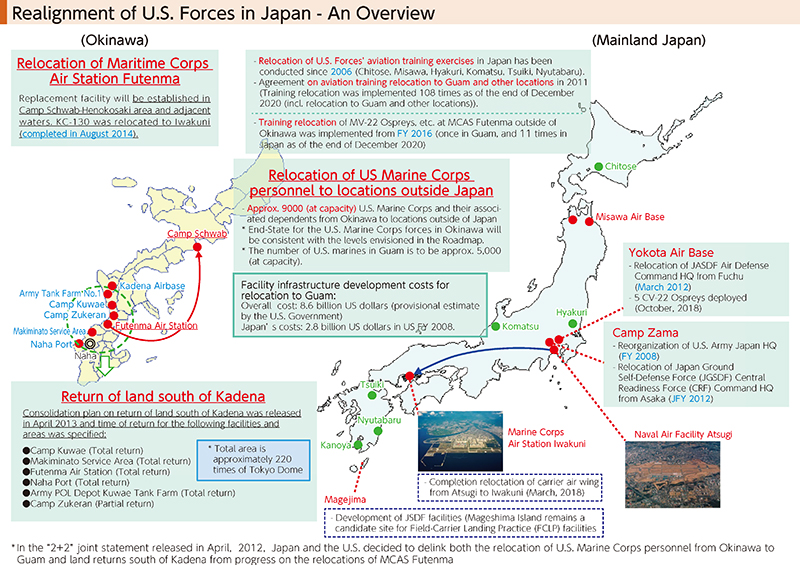

(3) Realignment of U.S. Forces in Japan

The Government of Japan will continue to make every effort to mitigate the impact on local communities, including Okinawa, by soundly promoting the realignment of U.S. Forces in Japan, including the prompt relocation to Henoko and the return of MCAS Futenma, while still maintaining the deterrence capabilities of said forces.

In the joint statement issued by Japan and the U.S. in February 2017, the two governments affirmed, for the first time in a document at the summit level, that constructing the Futenma Replacement Facility (FRF) at the Camp Schwab-Henokosaki area and adjacent waters is the only solution to avoid the continued use of MCAS Futenma. Furthermore, in the “2+2” joint statement in April 2019, the two governments reaffirmed their understanding that the plan to construct the FRF at the Camp Schwab-Henokosaki area and adjacent waters is the only solution that avoids the continued use of MCAS Futenma, and underscored their strong determination to achieve its completion as soon as possible.

Japan and the U.S. will also continue to work closely on the steady implementation of the relocation of approximately 9,000 U.S. Marine Corps from Okinawa to outside the country such as Guam, which will begin in the first half of the 2020s, and on the return of land south of Kadena based on the April 2013 “Consolidation Plan for Facilities and Areas in Okinawa.”

In addition to the return of a major portion of the Northern Training Area (NTA, approximately 4,000 hectares) in December 2017, various return projects were advanced based on this Consolidation Plan. In March 2020, a portion of the warehouse area of the Facilities and Engineering Compound in Camp Zukeran (approximately 11 hectares) were returned, thereby realizing the return of all areas indicated as “Immediate Return” under the Consolidation Plan.

(4) Host Nation Support (HNS)

The security environment surrounding Japan is becoming increasingly severe and uncertain at a remarkably rapid pace. From the standpoint that it is important to ensure smooth and effective operation of U.S. Forces, Japan (USFJ) bears the rent for USFJ facilities and areas and the Facility Improvement Program (FIP) funding stipulated within the scope of the Japan-U.S. Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA). In addition to this, under the Special Measures Agreement (SMA), Japan also bears labor costs, utility costs and training relocation costs for USFJ.

In February 2021, the Government of Japan and the Government of the U.S. mutually decided to amend the current Special Measures Agreement, extending its validity through March 31. 2022. They also concurred on continuing negotiations toward an agreement on a new SMA to be effective from April 1, 2022.

(5) Various Issues Related to the Presence of U.S. Forces in Japan

To ensure the smooth and effective operation of the Japan-U.S. security arrangements and the stable presence of USFJ as the linchpin of these arrangements, it is important to mitigate the impact of U.S. Forces' activities on residents living in the vicinity and to gain their understanding and support regarding the presence of U.S. Forces. In particular, the importance of mitigating the impact on Okinawa, where U.S. Forces' facilities and areas are concentrated, has been confirmed between Japan and the U.S. on numerous occasions, including the Japan-U.S. Summit Meeting in April 2018 and the “2+2” meeting in April 2019. The Government of Japan will continue to work to address the realignment of U.S. Forces in Japan. At the same time, the Government of Japan has been making utmost efforts to make improvements in specific issues in light of the requests from local communities. Among these issues are preventing incidents and accidents involving U.S. Forces, abating the noise by U.S. Forces' aircraft, and dealing with environmental issues at U.S. Forces' facilities and areas, including the sound implementation of the Agreement on Cooperation in the Field of Environmental Stewardship of 2015 and the Agreement on Cooperation with regard to Implementation Practices relating to the Civilian Component of the United States Armed Forces in Japan of 2017. For example, when the large-scale leak of firefighting foam that contains Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) occurred at MCAS Futenma in April 2020, Japanese officials accessed the site five times based on the Supplementary Agreement on Environmental Stewardship, conducted water and soil sampling and released the results. In addition, there have been many COVID-19 cases among USFJ personnel since March. In response to this, the Government of Japan and USFJ issued a joint press release in July on USFJ's efforts to combat COVID-19, and are cooperating closely to prevent further spread of COVID-19 in Japan.

Since 2018, the TOFU: Think of Okinawa's Future in the U.S. program has been launched to provide an opportunity for high school and university students from Okinawa to witness for themselves what Japan's alliance partner, the U.S., is truly like, and the role that Japan plays in the international community, as well as to promote mutual understanding by having them interact with local important officials and young people in English. Due to the COVID-19 situation, this program was postponed in FY2019. On the other hand, the Project to Promote Exchanges and Enhance Mutual Understanding Between Japan and the United States was launched from December 2020 in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA) to facilitate cultural and educational exchanges between Japanese and American middle and high school students (see the Column on page 222).

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in cooperation with the United States Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA), has launched an exchange program since FY2020 between local middle and high school students and the children of personnel from the U.S. Forces, in regions where U.S. facilities and areas in Japan are located. This program aims to deepen mutual understanding among Japanese and U.S. middle and high school students through cultural and educational exchanges, as well as to nurture talents who can take an active role in the international community. The first program was held on December 5 and 6, at Misawa City of Aomori Prefecture. This column features the voices of Japanese students who participated in the program.

Kawamura Yukino, Daini Junior High School, Misawa City

At the beginning, simply introducing myself in English made me nervous. However, through interactions between Japanese and U.S. junior high school students, such as playing games and drawing pictures, I felt very happy as we were able to become closer to each other. I learned that despite the differences in language and culture, a strong desire to communicate can lead to mutual understanding between various people. From now on, I will value my own abilities as well as the abilities of others and engage in exchanges between Japan and the U.S. Misawa City has mountains, rivers, seas and lakes, making it a place with abundant resources. During the session where we considered ways to enhance the popularity of Misawa, we compiled and presented the ideas raised by all the participants. Through participation in this project, I feel that I have acquired some skills to listen to the opinions of others and broaden my own ideas. I am truly happy to have taken part in the program.

Ikeda Reika, Horiguchi Junior High School, Misawa City

At the start of the program, although I was able to understand what the U.S. participants were saying, I was unable to respond well to them, and I was vexed by the difficulty of communicating with them. However, we were able to exchange opinions with one another through trial and error, such as by drawing pictures, and using gestures. By the end, we had an enjoyable time. During the joint group session between Japanese and U.S. participants, I was amazed by the proactive attitude and leadership of the girls who took action immediately when they had an idea. At the same time, despite the differences in language and culture, I truly felt that working together toward the same goal helped to foster our friendship and deepen our ties naturally. I hope that there will be more such programs in the future that give us the opportunities to communicate directly with people from other countries.

Students engaging in discussions

Students engaging in discussions Students dancing together

Students dancing together(6) United Nations Command (UNC) and U.S. Forces in Japan

Coincident with the start of the Korean War in June 1950, the United Nations Command (UNC) was established in July of the same year based on UN Security Council resolution 83 in June and resolution 84 in July. Following the ceasefire agreement concluded in July 1953, UNC Headquarters was relocated to Seoul, South Korea in July 1957, and UNC (Rear) was established in Japan. Established at Yokota Air Base, UNC (Rear) currently has a stationed commander and four other staff and military attachés from nine countries who are stationed at embassies in Tokyo as liaison officers for UNC. Based on Article 5 of the Agreement Regarding the Status of the United Nations Forces in Japan, UNC may use the U.S. Forces' facilities and areas in Japan to the minimum extent required to provide support for military logistics for UNC. At present, UNC is authorized to use the following seven facilities: Camp Zama, U.S. Fleet Activities, Yokosuka, U.S. Fleet Activities, Sasebo, Yokota Air Base, Kadena Air Base, Marine Corps Air Station Futenma and White Beach Area.

In July 2019, a joint board was held between the Government of Japan and UNC that marked the first time in over 60 years that any substantial discussions had been held between the two sides over matters not concerning the usage of facilities and areas. The meetings saw discussions held over the situation on the Korean Peninsula, with the two sides reaching an agreement on notification procedures in case of unusual occurrences related to the United Nations Command Forces in Japan. The Government of Japan will continue to work closely with the UNC.