Diplomatic Bluebook 2018

Chapter 3

Japan's Foreign Policy to Promote National and Global Interests

4 Disarmament and Non-proliferation and the Peceful uses of Nuclear Energy8

- 8 For more details about Japan's policy in the fields of nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation, please refer to “Japan's Disarmament and Non- Proliferation Policy” (7th Edition) published in March 2016.

(1)Nuclear Disarmament

As the only country to have ever suffered atomic bombings, Japan has the responsibility to take the lead in efforts by the international community to realize a world free of nuclear weapons.

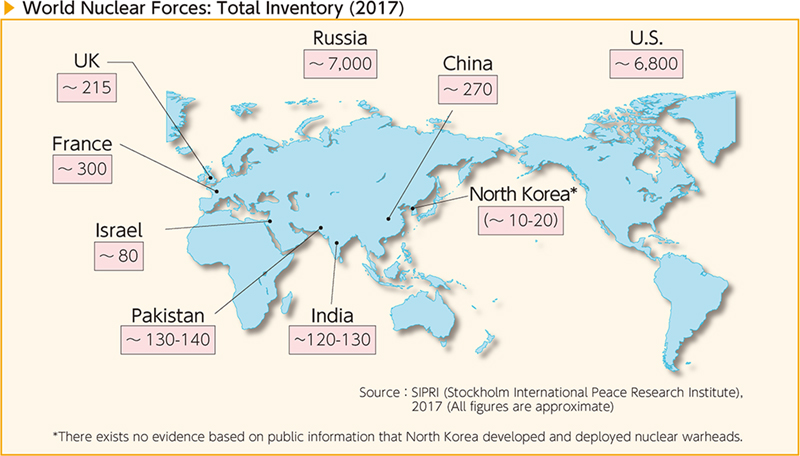

In recent years, amidst the deterioration in the global security environment, including North Korea's nuclear and missile development, differences in positions concerning the approach to nuclear disarmament have been emerging not only between nuclear-weapon and non-nuclear-weapon States, but also among non-nuclear-weapon States that are exposed to the threat of nuclear weapons and those that are not. Concerning these severe circumstances, it is necessary to gain the cooperation of both non-nuclear-weapon and nuclear-weapon States, and to persevere in putting in place realistic and practical measures in order to advance nuclear disarmament in a real manner.

In the area of nuclear disarmament, the United Nation's conference to negotiate the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons was conducted in 2017, and the treaty was adopted with a majority vote on July 7 (122 votes for, one vote against, and one abstained vote). Nuclear-weapon States and allies of NATO member countries, among others, did not participate the conference. Japan did not participate in the negotiations either. However, Japan attended the beginning of the conference and stated its position (See “Special Feature: Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons”).

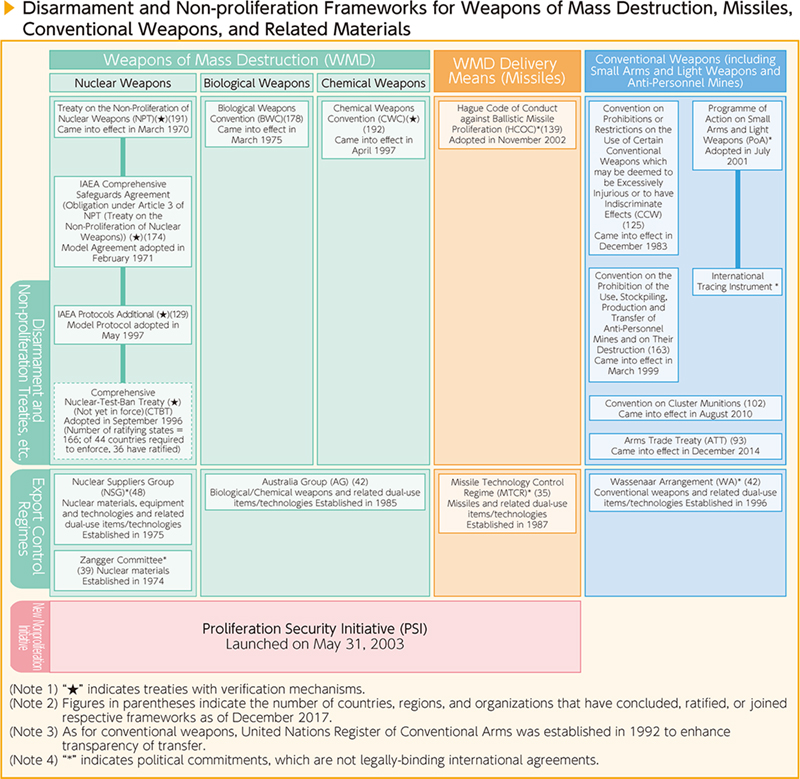

Japan continues to pursue nuclear disarmament persistently with the aim to realize a world free of nuclear weapons, by taking a bridging role between nuclear-weapon States and non-nuclear-weapon States through measures such as holding a meeting of the Group of Eminent Persons for Substantive Advancement of Nuclear Disarmament, submitting a draft resolution for the total elimination of nuclear weapons to the UN General Assembly, and utilizing the framework of the Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI), and by accumulating realistic and practical measures that also involve nuclear-weapon States, such as the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), and Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty (FMCT).

A Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT)

Japan attaches great importance on maintaining and strengthening the NPT, which is the cornerstone of the international nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation regime. At the NPT Review Conference, which is held once every five years with the aim of achieving the goals of the Treaty and ensuring compliance with its provisions, various discussions that reflected the international situation of the time have been held since the Treaty entered into force in 1970. At the NPT Review Conference held in 2015, discussions surrounding the issue of a weapons-of-mass-destruction-free zone in the Middle East and other topics could not reach a consensus, and the conference ended without an adoption of a final document. Against this backdrop, there is growing importance of efforts towards the NPT Review Conference in 2020, which marks the 50th anniversary of the Treaty's entry into force.

Foreign Minister Kishida attended the First Session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2020 NPT Review Conference, which was held in Vienna in May, and he appealed for the necessity to rebuild relationships of trust between nuclear-weapon and non-nuclear-weapon States. He also proposed three policies, namely enhancing transparency, improving the security environment, and raising awareness of the realities of the atomic bombings, and stated Japan's proposals on the pathway towards the elimination of nuclear weapons.

B Group of Eminent Persons for Substantive Advancement of Nuclear Disarmament

In May, Japan announced the establishment of a Group of Eminent Persons for Substantive Advancement of Nuclear Disarmament (EPG) at the first Preparatory Committee of the 2020 NPT Review Conference. The EPG consists of a total of 16 experts; six Japanese experts including the chairperson, and ten foreign experts from nuclear-weapon States and non-nuclear-weapon States including the States promoting the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. In November, the EPG's first meeting was held in Hiroshima. The EPG will make concrete recommendations that contribute to substantive advancement in nuclear disarmament after the second meeting to be held in the spring of 2018. Japan will input the recommendation to the Second Session of the Preparatory Committee of the 2020 NPT Review Conference (in Geneva) in April, 2018.

C The Non-proliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI)

The NPDI, which is a group of non-nuclear-weapon States from various regions established under the leadership of Japan and Australia in 2010, has taken a bridging role between nuclear-weapon and non-nuclear-weapon States and is taking the lead in efforts in the field of nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation through its concrete and practical proposals, based on the involvement of the Foreign Ministers of its Member States.

At the First session of Preparatory Committee for the 2020 NPT Review Conference held in May 2017, the NPDI submitted a total of six working papers, including a working paper on transparency, as a part of its concrete contributions to the discussions. In September, Foreign Minister Kono co-hosted the 9th Ministerial Meeting of the NPDI in New York, with Germany. In addition to affirming collaboration and cooperation towards the 2020 NPT Review Meeting, a statement that strongly condemns North Korea's nuclear tests and missile launches was also issued.

9th Non-proliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI) Ministerial Meeting (September 21, New York, U.S. (Permanent Mission of Germany to the United Nations))

9th Non-proliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI) Ministerial Meeting (September 21, New York, U.S. (Permanent Mission of Germany to the United Nations))D Initiatives Through the United Nations

(A) Resolution on Nuclear Disarmament

Since 1994, Japan has annually submitted a draft resolution on the elimination of nuclear weapons to the UN General Assembly. This draft resolution incorporates current issues that are related to nuclear disarmament, as well as concrete and practical measures towards the total elimination of nuclear weapons. In 2017, the resolution aimed to rebuild relationships of trust among all states, bridge gaps among states with different positions, and provide a common ground for the international community to work together to address this issue, so as to achieve substantive progress in nuclear disarmament. As a result, this resolution was adopted with the wide support of 156 states at the UN General Assembly in December. Nuclear-weapon States such as the U.S. and the UK, both of which abstained from voting on the same resolution in the previous year, became co-sponsoring states for the resolution. France also voted for its adoption. The resolution was supported by many states, including 95 out of the 122 states that had voted in support of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. In addition to Japan's draft resolution on the elimination of nuclear weapons, a couple of resolutions that deal comprehensively with nuclear disarmament were also submitted to the UN General Assembly. Japan's draft resolution enjoyed the support of a larger number of states in comparison with these other draft resolutions, and has continued to have the wide support of states of difference in position in the international community for more than 20 years.

(B) United Nations Conference on Disarmament Issues

The UN Conference on Disarmament Issues, organized by the UN, has been held in Japan almost every year since 1989 in cooperation with local government bodies and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In November 2017, the 27th UN Conference on Disarmament Issues was held in Hiroshima. 60 representatives from two international organizations and 12 countries, such as UN representatives including Under-Secretary-General and High Representative for Disarmament Affairs, Izumi Nakamitsu, and senior government officials, experts, NGO representatives, and media representatives from various countries attended the Conference. Parliamentary Vice-Minister for Foreign Affairs Okamoto attended the Conference on behalf of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and gave a speech at the opening session. In the speech, Parliamentary Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs Okamoto mentioned Japan's effort and approaches towards nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation based on the current severe security environment, in which the launch of a ballistic missile by North Korea took place during the early dawn of the opening day of the conference. At the Conference, representatives from the atomic-bombed sites of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as well as civil society expressed their hopes for the realization of a world free of nuclear weapons. The participants also discussed education on disarmament and non-proliferation aimed at firmly passing on to next generations the correct understanding of the realities of atomic bombings across borders and generations, and the current state and future outlook of nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation after the adoption of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW).

E Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT)

Japan attaches great importance on the early entry into force of the CTBT as a realistic and practical measure of nuclear disarmament where both nuclear-weapon and non-nuclear-weapon States can participate. During the two years from September 2015 to September 2017, Japan served as a co-coordinator for facilitating entry into force of the Treaty, along with Kazakhstan, and has taken the lead in initiatives toward the early entry into force of the CTBT. In March 2017, Japan made a voluntary contribution of approximately 290 million Japanese yen to the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), with the aim of strengthening the detection capabilities of the International Monitoring System (IMS) for nuclear tests. In July, a regional conference to promote the entry into force of the CTBT in the Asia-Pacific region was convened in Tokyo. In August, Foreign Minister Kono had a meeting with Executive Secretary of CTBTO Zerbo and affirmed that Japan will continue to offer close cooperation towards the early entry into force of the CTBT. Furthermore, in September, Foreign Minister Kono attended the 10th Conference on Facilitating the Entry into Force of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty held in New York. He condemned North Korea's nuclear tests as a grave challenge against the international disarmament and non-proliferation regime, and stated Japan's resolve, as a former co-coordinating country, to continue leading efforts by the international community towards facilitating the entry into force of the CTBT.

10th Conference on Facilitating the Entry into Force of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) (September 20, New York, U.S. (UN Headquarters))

10th Conference on Facilitating the Entry into Force of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) (September 20, New York, U.S. (UN Headquarters))F Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty (FMCT: Cut-off Treaty)9

The FMCT has great significance from the perspectives of both disarmament and non-proliferation, as it prevents the emergence of new states which possess nuclear-weapon by banning the production of fissile materials (such as highly-enriched uranium and plutonium) that are used in nuclear weapons, and at the same time, limits the production of nuclear weapons by nuclear-weapon States. However, for many years, an agreement has not been reached on the commencement of negotiations of the treaty in the Conference on Disarmament (CD). In view of this situation, it was decided at the 71st UN General Assembly in December 2016 to establish an FMCT High-Level Experts Preparatory Group, and to hold the sessions of the Group in 2017 and 2018 to consider and make recommendations on the substantive elements of the treaty. In August 2017, the Group held its first session in Geneva, and Japan sent an expert to the meeting. Based on the discussions at the session, a report will be drawn up at the second meeting to be held in 2018, and submitted to the 73rd UN General Assembly that will be held in the same year.

- 9 A treaty concept that aims to prevent the increase in the number of nuclear weapons by prohibiting the production of fissile materials (such as enriched uranium and plutonium, etc.) that are used as the materials for the production of nuclear weapons and other nuclear explosive devices.

G Disarmament and Non-proliferation Education

As the only country to have ever suffered atomic bombings, Japan places great importance of education on disarmament and non-proliferation. Specifically, Japan has been actively engaged in efforts to convey the realities of the devastation caused by the use of nuclear weapons to people both within Japan and overseas, through activities such as translating the testimonies of atomic bomb survivors into other languages, conducting training courses for young diplomats from other countries in the sites of atomic bombings through the United Nations Programme of Fellowships on Disarmament10, providing assistance for holding atomic bomb exhibition overseas through its diplomatic missions overseas11, and commissioning atomic bomb survivors who have given testimonies of their atomic bomb experiences as “Special Communicators for a World without Nuclear Weapons.”

With the atomic bomb survivors aging, it is becoming increasingly important to pass on the current understanding of the realities of the use of atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki across the generations and borders. In this regard, since 2013, Japan has been commissioning youths within Japan and overseas as “Youth Communicators for a World without Nuclear Weapons.” In November 2017, the 3rd Forum of Youth Communicators for a World without Nuclear Weapons was held in Hiroshima, with the aim of revitalizing the activities of the Youth Communicators, and strengthening their networking within Japan and overseas. Youth Communicator alumni from Japan and overseas attended the Forum.

Japan has also been engaged in the invitation of them to Hiroshima and Nagasaki through various invitation programmes. In FY2016, more than 2,400 people visited Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

- 10 Implemented since 1983 by the UN to nurture nuclear disarmament experts. Participants of the program are invited to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and efforts are made to promote understanding of the realities of atomic bombing through tours of the various museums, talks by victims about the experience of atomic bombing, etc.

- 11 Opened as a permanent exhibition about atomic bombing in New York (U.S.), Geneva (Switzerland) and Vienna (Austria), in cooperation with Hiroshima City and Nagasaki City. In 2017, the Hiroshima-Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Exhibition was held in Budapest (Hungary) and Hanoi (Vietnam), etc.

1. Overview/Background

Negotiations on the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (July 7, New York, U.S. ; Photo: Mainichi Shimbun)

Negotiations on the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (July 7, New York, U.S. ; Photo: Mainichi Shimbun)The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons was adopted with a majority vote on July 7, 2017 after two rounds of negotiations (March and June-July 2017) in the United Nations, on the basis of initiatives by the civil society and countries, such as Mexico and Austria, which led the discussions on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons. This Treaty became open for signature on September 20, 2017. It will enter into force 90 days after being ratified by 50 countries. As of February 28, 2018, 56 countries have signed the Treaty, of which five countries have ratified it.

On December 10, 2017, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), an international NGO advocating the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Foreign Minister Kono issued a statement, in which he welcomed both an increase in global awareness and heightened momentum towards nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation in the international community. In the statement, Foreign Minister Kono also expressed his respect for the efforts taken by the “Hibakusha” (atomic bomb survivors) of Hiroshima and Nagasaki who have engaged in activities over many years to speak about the realities of the atomic bombings. At the same time, Minister Kono also expressed his intention to advance practical and concrete measures towards nuclear disarmament, involving nuclear-weapon States.

2. Prohibitions Stipulated in the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons

Article 1 of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons stipulates that “Each State Party undertakes never under any circumstances to: (a) Develop, test, produce, manufacture, otherwise acquire, possess or stockpile nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices; (b) Transfer to any recipient whatsoever nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices or control over such weapons or explosive devices directly or indirectly; (c) Receive the transfer of or control over nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices directly or indirectly; (d) Use or threaten to use nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices; (e) Assist, encourage or induce, in any way, anyone to engage in any activity prohibited to a State Party under this Treaty; (f) Seek or receive any assistance, in any way, from anyone to engage in any activity prohibited to a State Party under this Treaty; (g) Allow any stationing, installation or deployment of any nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices in its territory or at any place under its jurisdiction or control.”

3. Views of the Government of Japan

As Japan is the only country that has experienced nuclear devastation during war, the Government of Japan shares the goal of the total elimination of nuclear weapons with the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. On the other hand, North Korea's nuclear and missile development is an unprecedented, grave and imminent threat against peace and stability of Japan and the international community. As conventional weapons alone cannot effectively deter ones, such as North Korea, that threaten to use nuclear weapons, it is necessary to maintain the deterrence including nuclear deterrence under the Japan-U.S. Alliance.

As the Government of Japan works on nuclear disarmament, it is important to consider both humanitarian and security perspectives. The security perspective, however, is not taken into account in the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. If Japan participates in a treaty that categorically makes nuclear weapons illegal, nuclear deterrence will lose its justification, which could then expose the lives and properties of Japanese citizens to danger. This will cause a problem for the security of Japan. Furthermore, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons has neither gained support of nuclear-weapon States that possess nuclear weapons in reality, nor that of non-nuclear-weapon States that are exposed to the threat of nuclear weapons just like Japan. Hence, there are also concerns that the Treaty is generating a division in efforts in the international community to advance nuclear disarmament.

It is essential for the Government of Japan to steadily seek ways to advance nuclear disarmament in a realistic manner, while responding appropriately to real security threat to fulfill its responsibility to protect the lives and properties of Japanese citizens. Therefore, Japan will tenaciously advance concrete and practical measures, while fulfilling a bridge-building role in the international community including nuclear-weapon States and countries that support the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

(2) Non-proliferation

A Efforts to Prevent the Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction

Japan has been making efforts to strengthen non-proliferation regimes. As a member state of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Board of Governors designated by the Board12, Japan contributes to the activities of the IAEA in both the personnel and financial aspects. Yukiya Amano, who has been serving as Director General of the IAEA since 2009, was re-elected (for the third consecutive term) unanimously at the IAEA Board of Governors meeting held in March 2017, and his appointment was approved at the 9th General Conference (for the term from December 2017 to the end of November 2021). Director General Amano has established the vision of “atoms for peace and development,” discussed issues such as application of safeguards, seen to the implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)13, which is the final agreement concerning Iran's nuclear issues, and tackled the nuclear issues of North Korea. Director General Amano has also made efforts in addressing development challenges by using nuclear technology. These initiatives under the leadership of Director General Amano have been highly appraised by countries around the world. With respect to the IAEA safeguards, which are a central measure to the international nuclear non-proliferation regimes, Japan encourages other countries to conclude Additional Protocols (AP) of the IAEA safeguards14 by providing personnel and financial support for the IAEA's regional seminars, as well as through other fora. In addition to organizing national workshops aimed at promoting the conclusion of AP in Sudan and Ethiopia in April, a training course on the implementation of safeguards, hosted by the Integrated Support Center for Nuclear Nonproliferation and Nuclear Security (ISCN) of the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) was held for Iran in September. These initiatives were implemented through financial support disbursed through the Nuclear Nonproliferation Fund15, and contribute to promoting the conclusion of AP in Southeast Asia, Middle East, and Africa.

With respect to nuclear weapons, biological and chemical weapons, missiles16, and conventional weapons, Japan participates in relevant export control regimes, which are coordinating frameworks for countries supporting appropriate export controls and capable of supplying respective weapons and related dual-use goods and technologies. In particular, the Permanent Mission of Japan to the International Organizations in Vienna serves as the Point of Contact of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG).

In addition to actively taking part in the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI)17, Japan is working to promote understanding of the non-proliferation regime and strengthen regional efforts particularly in Asia by hosting the Asia Senior-Level Talks on Non-Proliferation (ASTOP)18 and the Asian Export Control Seminar19. Furthermore, through the International Science and Technology Center (ISTC), Japan is also contributing to international scientific cooperation and efforts to prevent the proliferation of knowledge and skills in the field of weapons of mass destruction. More specifically, scientists from Central Asia and other countries, who were previously involved in research and development focused on weapons of mass destruction and their delivery systems, are now undertake research for peaceful purposes funded by the ISTC.

To strengthen the implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 154020, which was adopted in 2004 with the aim of preventing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and their delivery means (missiles) to non-state actors, Japan has contributed approximately 1 million US dollars. This contribution is primarily being used to support initiatives aimed at strengthening the non-proliferation regime in Asia.

- 12 13 countries designated by the IAEA Board of Governors. Japan and other countries such as G7 members that are advanced in the field of nuclear energy are nominated.

- 13 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)

Sets forth detailed procedures for imposing constraints on Iran's nuclear activities while ensuring that they serve peaceful purposes, and for lifting the sanctions that have been imposed until now.

<Main measures undertaken by Iran>

・Constraints on enriched uranium-related activities

・Limits the number of centrifuges in operation to 5,060 units

・Upper limit of enriched uranium at 3.67%, and limit on the amount of stored enriched uranium at 300 kg, etc.

・Constraints on Arak heavy-water nuclear reactor, and reprocessing

・Redesign/remodeling of the Arak heavy-water nuclear reactor such that it is not able to produce weapon-grade plutonium, and transfer of spent fuel out of the country

・No reprocessing including for research purposes, no construction of reprocessing facilities, etc. - 14 A protocol concluded between a respective country and the IAEA in addition to a Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement, etc. The conclusion of the Additional Protocol expands the scope of nuclear activity information that should be declared to the IAEA, and gives the IAEA strengthened rights to check for undeclared nuclear materials and nuclear activities. As of September 2017, 129 countries have concluded the Additional Protocol.

- 15 A special contribution that Japan makes independently to the IAEA, with the aim of strengthening the international non-proliferation regime. Established in 2001 based on arrangements with IAEA.

- 16 Apart from export control regimes, the Hague Code of Conduct against Ballistic Missile Proliferation (HCOC) addresses the proliferation of ballistic missiles based on the principle of exercising restraint in their development and deployment. 139 countries have subscribed to the HCOC.

- 17 A framework established in May 2003 to prevent the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, their delivery systems, and related materials, in which endorsing states discuss and implement possible measures within the scope of international and domestic law. 105 countries have endorsed the PSI as of December 2016. Japan hosted two PSI maritime interdiction exercises in 2004 and 2007, an Operational Experts Group (OEG) meeting in November 2010 in Tokyo, and an air interdiction exercise in July 2012. Japan has also participated in events hosted by other countries, including the May 2013 tenth anniversary High-Level Political Meeting in Poland, the January 2016 Mid-Level Political Meeting in the U.S., the August 2017 OEG meeting in Singapore, and the September 2017 Maritime Interdiction Exercise Pacific Protector 17 in Australia.

- 18 A multilateral meeting hosted by Japan to discuss various issues related to the strengthening of the non-proliferation regime in Asia with the participation of the ten ASEAN Member States, China, the ROK, India, the U.S., Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and France. The ASTOP was most recently held in January 2018.

- 19 A seminar hosted by Japan to exchange views and information towards the objective of strengthening export controls in Asia, with the participation of export control officials from Asian countries and regions. It is organized annually in Tokyo since 1993. The seminar was most recently held in February and March 2018 and attended by approximately 30 countries and regions.

- 20 Adopted in April 2004, Resolution 1540 requires all countries to: (1) exercise restraint in providing support to terrorists and other non-state actors attempting to develop weapons of mass destruction; (2) enact laws prohibiting the development of weapons of mass destruction by terrorists and other non-state actors; and (3) implement domestic controls (protective measures, border control, export controls, etc.) to prevent the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. The resolution also establishes under the UN Security Council the 1540 Committee composed of Security Council members, with a mandate to review and report to the Security Council the implementation status of Resolution 1540.

B Regional Non-proliferation Issues

North Korea's development of nuclear and missile programs is a grave and urgent threat to international peace and security, and poses a serious challenge to the global nuclear non-proliferation regime centered on the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).

In the two years since 2016, North Korea has conducted three nuclear tests and launched as many as 40 ballistic missiles. The UN Security Council adopted Resolution 2270 in March 2016, Resolution 2321 in November 2016, and Resolutions 2356, 2371, 2375 and 2397 in 2017. However, North Korea has failed to comply with the series of resolutions, and has neither shown any intention nor taken any concrete action towards denuclearization.

The report issued by the Director General of the IAEA in August 2017 stated that throughout the period of observation by the IAEA on the situation of nuclear development in North Korea, indications of operation were observed at the 5MWe graphite-moderated reactor in Nyongbyon, including the discharge of water vapor and outflow of cooling water. This report further stated that while signs of operation were not observed at a facility deemed to be a reprocessing plant, there were indications that what was deemed to be within the fuel fabrication facility had been used. The report also announced the establishment of a new team within the IAEA to tackle North Korea's nuclear issues, and stated that the IAEA is ready to return to North Korea immediately if the relevant countries reach a political agreement, if approved by the IAEA Board of Governors, and if there is such a request from North Korea.

On its part, Japan will continue to work closely with the relevant countries, including the U.S. and the ROK, and strongly demand that North Korea steadily implement measures aimed at the abandonment of its nuclear and missile programs. In addition, to ensure that countries fully and strictly implement sanctions imposed through the UN Security Council Resolutions, Japan will work on capacity building for export controls particularly in Asia (See 2-1-1 (1)).

On the other hand, with regard to Iran's nuclear issue, in July 2015, the EU3 (the UK, France, Germany, and EU) + 3 (the U.S., China, and Russia) and Iran agreed on the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). The JCPOA imposes restrictions on Iran's nuclear activities while ensuring that they serve peaceful purposes, and clearly sets forth the procedures for lifting the sanctions that have been imposed until now, alongside the implementation of measures by Iran. The UN Security Council Resolution 2231 was also adopted; this resolution endorses JCPOA, as well as requests to the IAEA to carry out the necessary verification and monitoring activities.

Iran and the IAEA conducted verification based on the “Road-map for the Clarification of Past and Present Outstanding Issues regarding Iran's Nuclear Program,” which covers the possible military dimensions of Iran's nuclear issue21. In December 2015, the IAEA Director General issued a Final Assessment Report22.

Furthermore, in January 2016, the IAEA verified that Iran had implemented some of the measures that it had committed to in the JCPOA. Consequently, based on UN Security Council Resolution 2231, some of the sanctions imposed through past relevant UN Security Council resolutions were terminated. Sanctions continue to be imposed on the transfer activities that are related to Iran's nuclear and missile activities.

Japan supports the JCPOA, and takes the position that its continuous implementation is important. Based on this position, when Foreign Minister Kishida visited Iran in October 2015, he expressed Japan's intention to cooperate in the field of nuclear safety and implementation of the IAEA safeguards and transparency measures. In addition, corresponding with the Japan-Iran Foreign Ministers' Meeting held on December 7, 2016, Japan decided to offer assistance, through IAEA, worth 550,000 Euros for cooperation in nuclear safety, and 1.5 million Euros for cooperation in safeguard measures, in order to support continuous implementation of the nuclear agreement. From September 25 to 29, 2017, a training course on the implementation of safeguards on Iran was held in Japan (organized by the IAEA, and hosted by the Integrated Support Center for Nuclear Nonproliferation and Nuclear Security (ISCN) of the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA)).

With regard to Syria's implementation of the IAEA security measures, little progress has been achieved, partly due to the Syria crisis. In order to clarify the facts, it is important for Syria to cooperate fully with the IAEA, and to sign and ratify the Additional Protocol, as well as to implement it.

- 21 Possible Military Dimensions (PMD)

In November 2011, the IAEA pointed out, through the Director General's Report, the “possible military dimensions (PMD)” of the signs of nuclear bomb development with regard to Iran's nuclear activities. The PMD comprises 12 items including the development of detonators. Thereafter, this has been treated as an important point of contention in consultations between Iran and the IAEA. - 22 The IAEA Director General's Final Evaluation Report on the Possible Military Dimensions (PMD) of Iran's Nuclear Issue (Summary), The report mentioned the following three points.

(1) All of the activities included in the “Road-map for the Clarification of Past and Present Outstanding Issues Regarding Iran's Nuclear Program” were implemented as scheduled.

(2) The IAEA assessed that Iran had conducted the activities relevant to the development of nuclear explosive device in its organizational structure before the end of 2003, and some activities took place after 2003. At the same time, the IAEA assessed that these activities did not advance beyond feasibility and scientific studies, and acquisition of certain relevant technical competences and capabilities. Also, the IAEA has no credible indications of activities in Iran relevant to the development of a nuclear explosive device after 2009.

(3) The IAEA has found no credible indications of the diversion of nuclear material in connection with the possible military dimensions to Iran's nuclear program.

C Nuclear Security

In recent years, international cooperation on “Nuclear Security” to prevent terrorist organizations from using nuclear materials or other radioactive materials has also been enhanced through various efforts by the IAEA, the UN and like-minded countries. To maintain the heightened momentum from the Nuclear Security Summit that was held in Washington, D.C. (U.S.) in 2016 and the International Conference on Nuclear Security organized by the IAEA, the Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism (GICNT) was held in Tokyo, Japan, in June 2017. Approximately 220 representatives from 74 countries and four international organizations participated in this event. State Minister for Foreign Affairs Sonoura delivered a keynote lecture, in which he explained that the Government of Japan will cooperate with the IAEA on measures to counter nuclear terrorism as the Olympic and Paralympic Games Tokyo 2020 approach, and expressed Japan's intention to strengthen measures to counter nuclear terrorism for major public events, and to contribute to enhancing nuclear security in the international community, particularly in the area of human resource development.

In February 2018, the signing of the Practical Arrangements between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan and the IAEA on Cooperation in the Area of Support to the Implementation of Nuclear Security Measures on the Occasion of the Olympic and Paralympic Games Tokyo 2020 took place in the presence of Foreign Minister Kono and Director General Amano of the IAEA.

(3) Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy

A Multilateral Efforts

Along with nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation, the peaceful uses of nuclear energy are considered to be one of the three pillars of the NPT. According to the Treaty, it is the “inalienable right” for any country that meets its obligations to nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation to develop nuclear research, production and use for peaceful purposes.

Due to such factors as growing global energy demand and the need to address global warming, many countries are planning to further develop or newly introduce a nuclear energy program23. Even after the Fukushima Daiichi accident, nuclear energy remains as an important energy source for the international community.

On the other hand, the nuclear materials, equipment and technologies used for nuclear power generation can be diverted to uses for military purposes, and a nuclear accident in one country may have significant impacts on its neighboring countries. For these reasons, with regard to the peaceful uses of nuclear energy, it is vital to ensure the “3S”24: (1) Safeguards; (2) Nuclear Safety (measures to ensure safety to prevent a nuclear accident, etc.); and (3) Nuclear Security. As the country that experienced the Fukushima Daiichi accident, it is Japan's responsibility to share with the rest of the world its experiences and lessons learned from the accident and to contribute in strengthening global nuclear safety. In this regard, Japan and the IAEA are working in cooperation. the IAEA Reponse and Assistance Network (RANET) Capacity Building Centre (CBC) was designated in Fukushima in 2013, where workshops are organized in May (twice), July, August, and October in 2017 for Japanese and foreign officials to strengthen their capabilities in the field of emergency preparedness and response.

Decommissioning, contaminated water management, as well as decontamination and environmental remediation, have been progressing steadily at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station. However, this work continues to be difficult in ways that are unprecedented in the world, and efforts are being made to tackle the tasks through the technology and collective knowledge of the world. Japan has been working closely with the IAEA since the occurrence of the accident. In 2017, Japan hosted marine monitoring experts missions (October), and held an Experts' Conference on environmental remediation (April and November) with the IAEA. In addition, after its publication of a report on the levels and impact of radiation from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station accident in 2014, the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) has held briefing sessions about the report in Fukushima Prefecture (one held in October for 2017).

Furthermore, it is necessary to disseminate appropriate information at an appropriate time in order to deal with the aftermath of the accident and move forward on reconstruction, while gaining support and correct understanding of the international community. From this perspective, Japan periodically releases a comprehensive report through the IAEA, covering matters including the progress of decommissioning, contaminated water management at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, results of the monitoring of air dose rate and radioactivity concentration in the sea water, and food safety. Briefing sessions are held for diplomatic corps, and information is also provided through diplomatic missions overseas.

Nuclear energy is applied not only to the field of power generation, but also to areas including human health, food and agriculture, environment, and industrial applications. Promoting the peaceful uses of nuclear energy in such non-power applications, and contributing to development issues, are becoming increasingly important as developing countries make up the majority of NPT member states. As Director General Amano upholds “Atoms for Peace and Development,” the IAEA also places great importance on technical cooperation for developing countries.

Japan has been providing active support for this cooperation through the Peaceful Uses Initiative (PUI) and other means. At the NPT Review Conference held in April 2015, Japan announced that it would be contributing a total of 25 million US dollars over the five years to the PUI. In 2017, Japan provided support through the PUI for projects, including measures against infectious diseases and natural disasters in developing countries.

- 23 According to the IAEA, as of December 2017, 448 nuclear reactors are in operation worldwide and 59 reactors are under construction (see the IAEA website).

- 24 IAEA's Safeguards, typical measures for non-proliferation, and Nuclear Safety and Nuclear Security are referred to as the “3S” for short.

B Bilateral Nuclear Cooperation Agreement

Bilateral nuclear cooperation agreements are concluded to secure a legal assurance from the recipient country, when transferring nuclear-related materials and equipment such as nuclear reactors to that country, that the transferred items will be used only for peaceful purposes. The agreements especially aim to promote the peaceful uses of nuclear energy and ensure non-proliferation.

Moreover, as Japan attaches importance to ensuring the “3S,” recent nuclear agreements between Japan and other countries set out provisions regarding nuclear safety, and affirm mutual compliance with international treaties on nuclear safety, while facilitating the promotion of cooperation in the field of nuclear safety under the agreements.

Numerous countries continue to express that they have high expectations for Japan's nuclear technology even after the Fukushima Daiichi accident. While taking into account the situation and intentions of the partner countries desiring to cooperate with Japan in this field, Japan can continue to provide nuclear-related materials, equipment, and technology with the highest safety standards. Furthermore, as bilateral nuclear cooperation, Japan is called upon to share with other countries its experience and lessons learned from the Fukushima Daiichi accident, and to continue cooperating with other countries on improving nuclear safety. When considering whether or not to establish a nuclear cooperation agreement framework with a foreign country, Japan considers the overall situation in each individual case, taking into account such factors as non-proliferation, nuclear energy policy in that country, the country's trust in and expectations for Japan, and the bilateral relationship between the two countries. As of the end of 2017, Japan has concluded nuclear cooperation agreements with Canada, Australia, China, the U.S., France, the UK, the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM), Kazakhstan, the ROK, Viet Nam, Jordan, Russia, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and India.

Masato Hori, Deputy Director

Integrated Support Center for Nuclear Nonproliferation and Nuclear

Security (ISCN), Japan Atomic Energy Agency

The author delivering the opening remarks at a training session

The author delivering the opening remarks at a training sessionDo you know about the International Atomic Energy Agency's (IAEA) safeguards and Additional Protocol?

As the peaceful uses of nuclear power spreads across the globe and the number of countries that possess nuclear material rises from year to year, the safeguards serve as an important framework for verifying that nuclear materials are used only for peaceful purposes and not for the production of nuclear weapons.

After the Gulf War, it was revealed that Iraq, which had been subjected to the IAEA's safeguards, was engaged in secret nuclear development. In response, the Additional Protocol was entered into force to give the IAEA greater authority and enhance the reliability of the safeguards.

In September 2017, I attended “The IAEA Additional Protocol: 20 Years and Beyond” held in Vienna in conjunction with the 61st IAEA General Conference, and organized under the leadership of the Government of Japan to mark the 20th anniversary since the formulation of the Additional Protocol. At this event, the IAEA and the respective countries delivered reports about the background of the formulation of the Additional Protocol as well as the current status of its enforcement, and reaffirmed the importance of the Additional Protocol. Of the 174 countries where the Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement is effective, the Additional Protocol has entered into force in 129 countries as of May 2017. In view of this situation, discussions were also held at the event on initiatives and challenges towards further increasing the number of countries where the Additional Protocol is effective.

Safeguards training (November 29)

Safeguards training (November 29)Once the Additional Protocol enters into force in a country, the country will be obligated to provide even more information to the IAEA, and in principle, allow the IAEA safeguards inspectors to access to any place at any time. Therefore, it is necessary to establish the corresponding domestic laws and systems. Since 2011, our organization, the ISCN, has been providing training and conducting seminars on the safeguards and the Additional Protocol for personnel from government agencies and nuclear power facilities of various countries, particularly in Asia. To date, 614 people have attended a total of 28 courses. In moving towards the entering into force of the Additional Protocol, many countries share common challenges including resource shortages, inadequate knowledge and lack of support from the Parliament, to name a few. At this event in Vienna, I shared the knowledge about these challenges, which I gained through the training, and contributed to discussions pertaining to future initiatives aimed at promoting the entering into force of the Additional Protocol.

To promote the entering into force of the Additional Protocol, there is a need to approach and appeal to relevant countries on a variety of occasions, and to provide necessary support. Seventeen countries and organizations participated in the Annual Meeting of the Asia-Pacific Safeguards Network (APSN) held from October 30 in Busan (Republic of Korea), and engaged in discussions about issues related to the safeguards and other topics, as well as shared best practices. To strengthen nuclear nonproliferation, it is necessary to continue such efforts. The ISCN, for its part, will also continue to cooperate with MOFA, MEXT, the IAEA, and other agencies and organizations, and work tirelessly to tackle challenges in promoting the entering into force of the Additional Protocol.

(4) Biological and Chemical Weapons

A Biological Weapons

The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC)25 is the only multilateral legal framework imposing a comprehensive ban on the development, production, and retention of biological weapons. However, the question of how to enhance the convention is a challenge, as it contains no provision regarding the means of verifying compliance with the BWC.

After the 6th Review Conference held in 2006, decisions were made to establish the Implementation Support Unit (fulfilling the functions of a secretariat), and to hold inter-sessional conferences twice a year; progress has been made in initiatives toward strengthening the implementation of the BWC.

At the 8th Review Conference held in November 2016, negotiations on inter-sessional activities broke down, resulting in holding only a Meeting of States Parties (MSP). However, at the MSP held in 2017, it was agreed that a meeting should be held on international cooperation, review on the progress of science and technology, domestic implementation, defense support, and systematic strengthening of the Convention.

- 25 Enacted in March 1975. The contracting states number 179 (as of December 2017)

B Chemical Weapons

The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC)26 imposes a comprehensive ban on the development, production, storage, and use of chemical weapons and stipulates that all existing chemical weapons must be destroyed. Compliance is ensured through the verification system (declaration and inspection) and that is why this Convention is a groundbreaking international agreement on the disarmament and non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. The implementing agency of the CWC is the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), which is based in the Hague, the Netherlands. Along with the UN, the OPCW has played a key role in the destruction of Syria's chemical weapons. Its extensive efforts towards the realization of a world free of chemical weapons were highly appraised, and the organization was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2013. Japan has provided financial support for OPCW activities concerning the elimination of chemical weapons in Syria. In addition, Japan, which has a highly developed chemicals industry and numerous chemicals factories, also accepts many OPCW inspections. Apart from these, Japan cooperates actively with the OPCW in concrete ways, such as measures to increase the number of member States, and strengthening domestic implementation measures by States Parties with the aim of increasing the effectiveness of the Convention.

Moreover, under the CWC, Japan aims to complete, as soon as possible, the destruction of chemical weapons of the former Japanese Army abandoned in territory of China by working in cooperation with China.

- 26 Enacted in April 1997. The contracting states number 192 (as of December 2017)

(5) Conventional Weapons

A Cluster Munitions27

Japan takes the humanitarian consequences brought about by cluster munitions very seriously. Therefore, in addition to taking steps to address this issue by victim assistance and unexploded ordnance (UXO) clearance, Japan is continuing efforts to increase the number of States Parties on Cluster Munitions (CCM)28 for its universalization. Besides, Japan is assisting with UXO clearance bomb disposal and victim assistance projects in Laos, Lebanon and other countries that suffer from cluster munitions29.

- 27 Generally speaking, it refers to a bomb or shell which enables numerous submunitions to be spread over a wide area by opening in the air a large container, which holds those submunitions. It is said that there is high possibility that many of them do not explode on impact, which creates problem of accidental killing or injury of civilian population.

- 28 Enacted in August 2010, it prohibits the use, possession, or production of cluster munitions, while obliging the destruction of stockpiled cluster munitions, and the clearance of cluster munitions in contaminated areas. As of December 2017, the number of contracting states and regions is 102, including Japan.

- 29 See the White Paper on Development Cooperation for specific efforts in international cooperation regarding cluster munition and anti-personnel mine.

B Anti-personnel Mines

2017 marks the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction (Ottawa Treaty)30. To date, Japan has continued to promote comprehensive measures with a focus on the effective prohibition of anti-personnel mines and strengthening of support for mine-affected countries. As well as calling on countries in the Asia-Pacific region to ratify or accede to the Convention, Japan has, since 1998, provided support worth over 71 billion Japanese yen to 51 countries and regions to assist them in dealing with the consequences of land mines (for example, landmine clearance and victim assistance).

In December 2017, the 16th Meeting of the States Parties to the Anti-personnel Mine Ban Convention (the Ottawa Treaty) was held in Austria. At this Meeting, Japan looked back on its efforts to universalize the Ottawa Treaty in Japan to date, as well as its initiatives and achievements in supporting mine action. It also expressed Japan's continuous resolve to play a positive role with the aim of realizing a mine-free world.

- 30 While banning the use and production of anti-personnel mines, the Convention, which came into force in March 1999, obliges the destruction of stockpiled mines and clearance of buried mines. As of December 2017, the number of contracting states and regions is 164, including Japan.

C The Arms Trade Treaty (ATT)31

The ATT, which seeks to establish common international standards to regulate international trade in conventional arms and prevent illicit trade in them, came into force on December 24, 2014. As one of the original co-authors of the UN General Assembly Resolution that initiated a consideration of the Treaty, Japan has taken the lead in discussions and negotiations in the UN, and contributed actively to discussions in Conference of States Parties after the Treaty entered into force. In August 2018, Japan will be hosting the 4th Conference of States Parties to the Arms Trade Treaty in Japan as the chair country.

- 31 As of December 2017, the number of contracting states and regions to Army Trade Treaty (ATT) is 94. Japan signed the Treaty on the day that it was released for signing, and in May 2014, became the first country in the Asia Pacific region to become a contracting state.

D Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW)32

The Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) prohibits or restricts the use of conventional weapons that are deemed to be excessively injurious or to have indiscriminate effects, and comprises a framework Convention that sets forth the procedural matters, etc., as well as five annexed Protocols that regulate the individual conventional arms, etc. The framework Convention came into force in 1983. Japan has ratified the framework Convention and the annexed Protocols I to IV, including the revised Protocol II. In December 2017, the first meeting of the Group of Governmental Meeting of Experts on Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (LAWS) was held, in response to concerns among the international community against a background of the growing military use of robots in recent years.

- 32 As of December 2017, 125 countries and regions have ratified the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW).

E Small Arms and Light Weapons

Described as “weapons of mass destruction” in terms of the carnage they cause, small arms and light weapons continue to proliferate due to their ease of operation, and are one of the causes behind the drawing out and escalation of conflict, as well as hindrance to the restoration of public security and post-conflict reconstruction and development. Since 1995, Japan has been making an annual submission to the UN General Assembly of a resolution on small arms and light weapons, which has consistently been adopted by consensus. Japan supports various projects to tackle small arms and light weapons across the globe, including weapons recovery and disposal programs and training courses.