A Journalist’s Perspective on Japan’s ODA

[Wycliffe Muga]

HOW JAPAN LAID THE INDISPENSABLE FOUNDATION FOR KENYAN TOURISM TAKEOFF – AND THE CONSERVATION OF KENYA’S ICONIC WILDLIFE

The Moi International Airport, which was expanded with aid from Japan. (Photo: JICA)

In late July 2015, two news items in the Kenyan media were received as good news.

First, was that Britain had withdrawn its travel advisory issued some months previously, discouraging its citizens from making all but essential any trips to the Kenya coast.

Second, was that the German airline Lufthansa was resuming regular flights to Kenya, after a 10-year absence.

The reason all this was considered good news is that both Britain and Germany are key tourism source markets for Kenya. Regular flights to Nairobi from Frankfurt facilitated greater tourist arrivals. Likewise, withdrawal of the British travel advisory opened the way for more tourists to visit.

Conservation of Kenya’s iconic wildlife

All this needs to be put into perspective for readers who may not appreciate why the steady flow of European visitors to Kenyan beach resorts and safari lodges means so much to the country:

In January 2015, at a time when Kenyan tourism was in a deep downward spiral owing to fears over insecurity, ‘Swara’ magazine, the influential wildlife and conservation publication of the East African Wildlife Society, interviewed Mr. Jake Grieves-Cook.

He is one of the most authoritative voices in Kenyan tourism as a former chairman of the first stakeholders’ membership organization, the Kenya Tourism Federation (KTF); and then the government’s independent tourism marketing agency, the Kenya Tourism Board (KTB).

His views, outlined in this interview, illuminate the central role that tourism plays in the Kenyan economy:

“This (lack of tourists) will mean the loss of thousands of jobs, a big reduction in tax revenue and a lack of income for KWS, the parks, reserves and conservancies…Our tourism industry in Kenya is closely linked to many other sectors of the economy which are suppliers of goods and services for tourists such as agriculture, transport, aviation, banking, insurance, breweries and soft drinks, food producers, printers, car dealers, fuel companies and many others, as well as being an important source of tax revenue for central and county governments”

Tourism is a key driver of the Kenyan economy. And most impressive is that tourism’s contribution to GDP has risen from a modest US$0.7 billion in 1988, to the current US$6.0 billion. (Six billion USD is 12% of Kenya’s GDP)

Tourist arrivals have also increased over the years. Thus, the number of tourist arrivals, which was 0.7 million in 1988, showed a dramatic increase to the current 1.7 million.

The long string of beach hotels

It is widely appreciated within Kenya that the tourism sector achieved lasting success largely because the government of Switzerland helped set up Utalii College, which remains the premier hotel school in East Africa.

Utalii, set up in the early 1970s, was indispensable in training the skilled manpower for hotels, lodges and camps catering for the increasing number of tourists.

However these well-trained young people would not have had very many jobs in Kenya - nor would Kenyan tourism have taken off so spectacularly - if it were not for a series of strategic Japanese infrastructure projects implemented from the mid-1970s to 1990s.

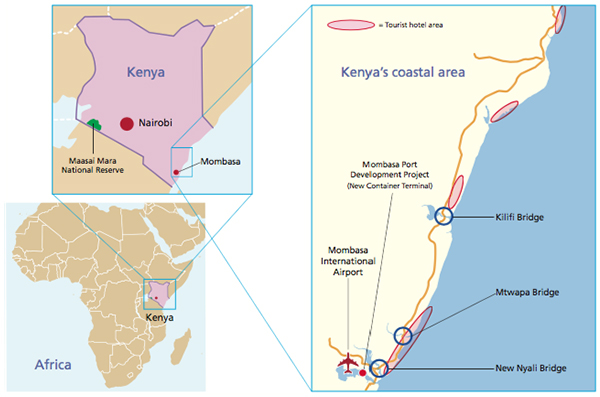

The success story of Kenya’s tourism had its foundation laid by four landmark projects by Japan at the Coast. They are the New Nyali Bridge in Mombasa built from 1975-1980; phased expansion of Moi International Airport in Mombasa from the early 1980s to the mid-1990s; and the Kilifi and Mtwapa bridges over the same period.

These indispensable infrastructure projects then allowed investors to then build the long string of beach hotels along the Kenya coast (about 105 “tourist class” hotels in total) from Nyali in Mombasa County all the way to Mambrui in Malindi, Kilifi County. In the process, not only were thousands of jobs created, but game lodges and tented camps in the interior of Kenya also benefited.

This, in turn, proved to be the key to sustaining ongoing conservation of Kenya’s wildlife; and indeed, through the implementation of these infrastructure projects, Japan played a central role in ensuring the survival of Kenyan wildlife.

The New Nyali Bridge completed with aid from Japan (Photo: JICA)

All-inclusive tours

To understand the significance of these projects, bear in mind that despite the euphoria over resumption of flights by Lufthansa, most tourists do not come to Kenya aboard such scheduled flights. Lufthansa’s return is more emblematic of increasing interest in Kenyan investment opportunities by European corporations. Major airlines like Lufthansa may well bring tourists to Kenya, but they are actually more likely to bring business travelers. For more than one million tourists who come specifically to sample the sunny coast and go on safaris, charter airlines are the key.

Indeed, the great majority of tourists on all-inclusive tours, which fly them in on charter airlines, mostly land in Mombasa, at the Moi International Airport. The German tourist, for example, is more likely to fly to Kenya on the leisure airline Condor, which is partially owned by Lufthansa.

Likewise, British tourists are more likely to land in Mombasa aboard such charter airlines as Thomson, and First Choice, than to land in Nairobi on the daily British Airways flight from London.

So the expansion of Moi International Airport — supported by Japan — was absolutely central to the expansion of coastal tourism, enabling many more tourists to land in Mombasa.

Opening up coastal tourism bottlenecks

But landing in Mombasa is one thing. Going by road to the beach resorts is another. And for many years up to the 1980s, as the town of Mombasa grew into a city, the “Old Nyali Bridge” — a floating pontoon bridge — was a major bottleneck in any road trip to the North Coast where most of the beach hotels were. Just one accident on that bridge, and traffic would stop for hours.

Nor was that the only bottleneck. At Mtwapa, a few miles beyond Old Nyali Bridge, ferry service was irregular. Those who sought the golden sands of Malindi took yet another ferry service – the Kilifi Ferry.

The Japanese infrastructure projects changed all this by building modern bridges served by wide roads, as it had done for the New Nyali Bridge in Mombasa.

Once they landed in Mombasa, these bridges (Nyali, Mtwapa and Kilifi, completed with Japanese support by the late 1990s) made it easy for tourists to reach any of the beach hotels along the coastal strip.

This transformed the Kenyan coast. The dozen or so beach hotels that existed in the early 1970 increased to today’s 105 tourist holiday resorts, in addition to apartment complexes and holiday homes.

And onto the Maasai Mara

But the coast is not the only region in Kenya which has benefitted from Japanese infrastructure projects. The Kenyan game parks, famous for their ‘safari’ experience, have also benefitted to an extent that it can be argued that these infrastructure projects were indispensable key to the effort to conserve Kenyan wildlife.

The great majority of tourists, who come to Kenya, are average middle-class Europeans who, as already outlined, make bookings for all-inclusive “package tours.” Only the richer visitors, come directly for safaris to the game parks.

These package tours will often include a return ticket from Europe; two or three weeks at some beach resort; and also a few nights at a safari lodge or camp, in one of Kenya’s game parks. So in general, full bookings at the coast, translate directly to more bookings for the game lodges and camps.

In a good year, all such lodges and camps in the Maasai Mara Game Reserve – Kenya’s most famous tourist destination – are fully booked from July to December.

And if you go to the Moi International Airport in Mombasa at any point during those months, you will find this airport being heavily utilized, not only by the “long-haul” charter flights bringing in tourists directly from Europe; but also small aircraft – carrying 12 to 15 passengers – flying out to the camps and lodges in the Maasai Mara Game Reserve, carrying tourists who arrived in Kenya earlier.

All these lodges and camps and hotels in the game parks – over 200 in the Maasai Mara alone – represent direct employment for approximately 60,000 Kenyans, and economic opportunity for an estimated 500,000 more.

But in addition to employment, there is the fact that this flow of tourist money paid for entry into the game parks is the key to the survival of the wild animals.

As Jake Grieves-Cook pointed out, “Tourism is the biggest contributor to conservation and if we allow our nature-based safari tourism to collapse, this will have a massive negative impact on conservation of Kenya’s iconic wildlife.”

So long as tourism flourishes in Kenya, the wild animals will remain protected. Yet none of this would have been possible without the far-sighted investments in coastal infrastructure made possible by Japan over the last two decades.

The British, the Germans, the Italians and the Americans may well form our core tourism markets and account for the largest number of tourists coming to Kenya.

But they would not have been coming in such large numbers, were it not for the Japanese.

Written (originally in English) by author Wycliffe Muga, columnist and weekend editor of the Kenyan newspaper Star.

And more yet to come

This however is not the last word on Japanese assistance in the planning and implementation of long-term-impact infrastructure projects in Kenyan Coast.

Indeed the largest such project currently underway, is set to provide massive benefits not only to the people of Kenya, but even more to those of various landlocked nations in the East Africa region such as Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and South Sudan.

This is the Mombasa Port Development Project, which is set to double the port’s capacity to handle container freight, from its current capacity of 480,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU) to 990,000 TEU by 2017.

Those five nations have a total population of about 100 million people.

And there is not one of them, who will not benefit — directly or indirectly — from the huge expansion and improved efficiency of the port of Mombasa, currently being undertaken with the financial support and technology transfer from Japan.

Main Text | Statistics and Reference Materials | Stories from the field | Master Techniques, From Japan to the World | ODA Topics | A Journalist’s Perspective on Japan’s ODA