Diplomatic Bluebook 2016

Chapter 3

Japan’s Foreign Policy to Promote National and Worldwide Interests

2.Japan-U.S. Security Arrangements

(1) Overview of Japan-U.S. Security Relationship

Under the security environment surrounding Japan which is becoming increasingly severe, it is indispensable to strengthen the Japan-U.S. Security Arrangements and to enhance the deterrence of the Japan-U.S. Alliance not only for the peace and security of Japan but also for the peace and stability of the Asia-Pacific region. Based on the robust bilateral relationship confirmed through such meetings as the Japan-U.S. Summit Meeting in April 2015, Japan and the U.S. are further enhancing their deterrence and response capabilities under the New Guidelines and the Legislation for Peace and Security. Through such efforts, Japan and the United States have been expanding and strengthening cooperation in a wide range of areas, including ballistic missiles defense, cyberspace, outer space, and maritime security. Japan and the U.S. have been working closely on the realignment of U.S. Forces in Japan, including the relocation of Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) Futenma and the relocation of U.S. Marine Corps in Okinawa to Guam, in order to mitigate impact on local communities, including Okinawa, while maintaining the deterrence of the U.S. Forces in Japan.

(2) Japan-U.S. Security and Defense Cooperation in Various Fields

A. Revision of the Guidelines for Japan-U.S. Defense Cooperation (the “Guidelines”)

At the October 2013 meeting of the Japan- U.S. Security Consultative Committee (“2+2”), the two governments agreed to initiate a task of revising the Guidelines. The New Guidelines were announced at the “2+2” in April 2015. Under the security environment surrounding Japan which is becoming increasingly severe, the New Guidelines ensure the review and update of the general framework and policy direction of the Japan-U.S. defense cooperation. On November 3, Japan and the United States agreed at the Subcommittee for Defense Cooperation (SDC) to establish the Alliance Coordination Mechanism (ACM) and the Bilateral Planning Mechanism (BPM) for enhancing the effectiveness of the New Guidelines. Interpersonal exchange between top-officials is increasingly vigorous, with visits of Admiral Harris, U.S. Pacific Commander to Japan in June 2015 and February 2016, as well as General Dunford of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in November 2015. Through these efforts, Japan will continue to promote security and defense cooperation with the U.S., further enhancing the deterrence and response capabilities of the Alliance.

B. Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD)

Japan has been making steady efforts to develop the BMD system while continuing cooperation with the U.S., including the steady implementation of joint development of the Standard Missile 3 (SM-3) Block IIA since 2006. In light of the expectation that Japanese domestic companies’ participation in the manufacturing of the Aegis System contributes to strengthening the security and defense cooperation with the United States, in July, the Government of Japan permitted transfer of the components and software for the Aegis Display System to the U.S.

C. Cyberspace

The two countries held the third Japan-U.S. Cyber Dialogue in Tokyo in July 2015. Based on the necessity for whole-of government efforts between Japan and the U.S., participants from both sides had a follow-up discussion on the outcome of the second dialogue held in April 2014. They also discussed a wide range of areas for Japan-U.S., cooperation in cyberspace, including awareness about the situations, protection of critical infrastructure, and cooperation in the international arena.

D. Outer Space

Japan and the U.S. discussed a wide range of cooperation on space, including in the area of security at the Space Security Dialogue (Deputy Director-General level consultation) in February, and at the Meeting of the Japan-U.S. Comprehensive Dialogue on Space in September. The two countries are undertaking further space security cooperation, including through mutual exchange of information in the field of Space Situational Awareness (SSA), and efforts to ensure the resiliency of space assets (i.e. capability to maintain the function of facilities or systems under attack).

E. Trilateral Cooperation

Japan and the U.S. place importance on security and defense cooperation with allies and partners in the Asia-Pacific region. In particular, the two countries are steadily promoting trilateral cooperation with Australia, the ROK and India. At the Japan-ROK Summit Meeting and the Japan-U.S. Summit Meeting in November as well as the Japan-Australia Summit Meeting in December, the leaders affirmed that these trilateral cooperation promote the shared security interests of Japan and the U.S. and that it will contribute to improving the security environment in the Asia-Pacific region. Also, following the nuclear test and ballistic missile launch by North Korea in January and February 2016, the importance of trilateral cooperation among Japan, the U.S. and South Korea was reconfirmed at the Summit Meetings and Foreign Ministers’ Meetings between Japan and the U.S., and Japan and the ROK.

F. Information Security

Information security plays a crucial role in advancing cooperation within the context of the Alliance. The two countries are discussing ways to further improve information security systems, including introducing government-wide security clearances and enhancing counterintelligence measures (designed to prevent information leaks through espionage activities).

G. Maritime Security

In forums such as the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and the East Asia Summit (EAS), Japan and the U.S. stress the importance of solving maritime issues in accordance with international law. The New Guidelines announced in April also provide that Japan and the U.S. will cooperate closely with each other on measures to maintain maritime order in accordance with international law, including the freedom of navigation.

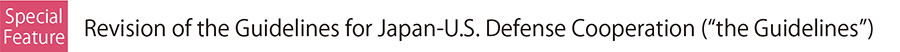

(3) Realignment of U.S. Forces in Japan

In the April “2+2” Joint Statement, Japan and the United States reaffirmed the two governments’ continued commitment to implement the existing arrangements on the realignment of U.S. Forces in Japan as soon as possible, while ensuring operational capability, including training capability, throughout the process. In this joint statement, both governments reaffirmed that the plan to construct the Futenma Replacement Facility (FRF) at the Camp Schwab-Henokosaki area and adjacent waters is the only solution to avoid the continued use of MCAS Futenma. In the Japan-U.S. Summit meetings held in the same month and November, both sides confirmed that the relocation of MCAS Futenma to Henoko is the only solution and President Obama stated that the U.S. will continue to cooperate on mitigating the impact on Okinawa. In October, Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga visited Guam, reviewing the progress of the project that begins the relocation of 9,000 U.S. Marine Corps from Okinawa to outside the country, including Guam, in the first half of the 2020s. He confirmed that the project will steadily progress through cooperation with the U.S. The nuclear-powered aircraft carrier USS “Ronald Reagan” arrived in Yokosuka in the same month, and Prime Minister Abe became the first sitting Japanese prime minister to set foot on a U.S. aircraft carrier.

With regard to return of land south of Kadena, the West Futenma Housing Area of Camp Zukeran was returned in March based on the “Consolidation Plan for Facilities and Areas in Okinawa” in April, 2013. Also, the “Implementation of Bilateral Plans for Consolidating Facilities and Areas in Okinawa” was announced by Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga and U.S. Ambassador Kennedy in December. To advance the process of U.S. Forces consolidation in Okinawa, which is designed to maintain a force posture capable of responding effectively to future challenges and operational contingencies across the region, while mitigating the impact of U.S. Forces on local communities, the two governments shared the view regarding the following measures on the return or joint use of facilities and areas in Okinawa.

(1) Futenma Air Station: The two governments confirmed that they would accelerate work on the return of the lands along the eastern side of MCAS Futenma (approximately 4 ha), which was confirmed at the Japan-U.S. Joint Committees in June 1990.

(2) Industrial Corridor, Camp Zukeran (Camp Foster): The two governments shared the views to establish a Joint Use Agreement promptly that will enable Ginowan City to begin construction in JFY 2017 of an elevated road above portions of Camp Zukeran (Camp Foster) to connect Route 58 to the former West Futenma Housing Area. The two governments will support Ginowan City’s access to the area for necessary work, including surveys to be started in 2016.

(3) Makiminato Service Area (Camp Kinser): The two governments shared the view to commence necessary work promptly to achieve in JFY 2017 return of the land (approximately 3ha) of Makiminato Service Area (Camp Kinser) adjacent to Route 58 for the purpose of widening the Route and reducing traffic congestion.

In addition, the two governments reaffirmed the significance and urgency of the return of a major portion of the Northern Training Area (approximately 3,987 ha) which was confirmed in the 1996 Special Action Committee on Okinawa (SACO) Final Report. They reconfirmed their commitment to complete the bilaterally agreed conditions necessary to facilitate the Northern Training Area’s expeditious return.

The Government of Japan will continue to strive for mitigating impact on Okinawa, while making all efforts to realize the return of MCAS Futenma as soon as possible, advancing its relocation to Henoko in accordance with the law.

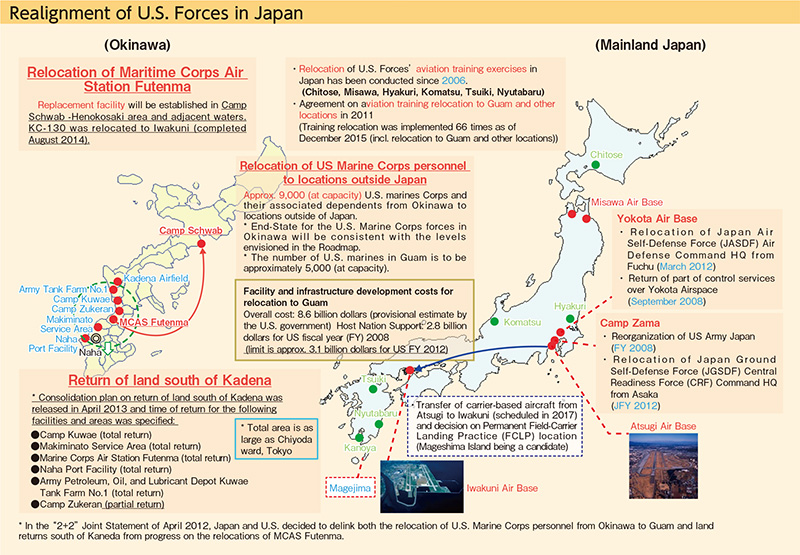

(4) Host Nation Support (HNS)

Under the security environment surrounding Japan which is becoming increasingly severe, from the standpoint that it is important to ensure smooth and effective operation of the USFJ, Japan bears the rent for USFJ facilities and areas and the Facility Improvement Program (FIP) funding within the scope of the Status of U.S. Forces Agreement. In addition to this, under the special measures agreements, Japan also bears labor costs, utilities costs, and training relocation costs for U.S. Forces in Japan.

Both governments had discussed the Host Nation Support (HNS) funding for the U.S. Forces in Japan since April 2016, and mainly agreed on the following in December 2015.

(1) In respect of the labor costs, the upper limit of the number of workers funded by Japan working at revenue generating welfare, recreation and morale facilities will be reduced from 4,408 to 3,893, and the upper limit of the number of workers funded by Japan engaged in the activities such as maintenance of assets and administrative works will be increased from 18,217 to 19,285.

(2) Utilities charges funded by Japan will be reduced from 72% to 61%, and the upper limit of the annual utilities costs funded by Japan will remain approximately 24.9 billion yen.

(3) The amount of FIP shall not fall below 20.6 billion yen for each FY.

(4) As a result, the amount of HNS to be funded by Japan for FY2020 will be approximately 189.9 billion yen.

At the Japan-U.S. Security Consultative Committee (“2 + 2”) convened in New York on April 27, 2015, the new Guidelines for Japan-U.S. Defense Cooperation (the new Guidelines) were announced for the first time in 18 years since 1997. The new Guidelines, amid the increasingly severe security environment surrounding Japan, are intended to review the general framework and policy direction on Japan-U.S. defense cooperation.

[Points of the new Guidelines]

Ensuring Japan’s peace and security

The new Guidelines, while ensuring the consistency with the security legislation (see Special Feature in Chapter 1), are intended to achieve Japan-U.S. cooperation seamlessly from peacetime to contingencies in light of different progresses in operational cooperation (ballistic missile defense, various training and exercises, etc.). Furthermore, the new Guidelines reaffirm the strong commitments by the U.S. under Japan-U.S. Alliance, such as strengthening coordination from peacetime, maintaining extended deterrence to Japan, and using U.S. Forces’ striking power in emergencies.

The “spread” of cooperation in the alliance, such as in regional and global areas and in outer space and cyberspace

The new Guidelines articulate the forms for Japan-U.S. cooperation for regional and global peace and security, as well as coordination with a third country, and reflect the expanded cooperation in new strategic areas such as outer space and cyberspace.

Mechanism to ensure the “effectiveness” of Japan-U.S. cooperation

The new Guidelines articulated the establishment of the Alliance Coordination Mechanism (ACM) in order to facilitate operational coordination of the Self-Defense Forces and the United States Armed Forces, as well as the Bilateral Planning Mechanism (BPM) in order to develop bilateral planning to respond to contingencies relevant to Japan’s peace and security (both announced on November 3, 2015).

In light of the increasingly severe security environment, we intend to further strengthen the deterrence and response capabilities of the Japan-U.S. Alliance under the new Guidelines.

Japan-U.S. “2+2” joint press conference

Japan-U.S. “2+2” joint press conference Japan-U.S. “2+2” Ministerial Meeting

Japan-U.S. “2+2” Ministerial Meeting(5) Various Issues Related to the Presence of U.S. Forces in Japan

To ensure the smooth and effective operation of the Japan-U.S. security arrangements and the stable presence of U.S. Forces in Japan as the linchpin of these arrangements, it is important to mitigate the impact of U.S. Forces activities on residents living in the vicinity and to gain their understanding and support regarding the presence of U.S. Forces. In particular, the importance of promoting mitigation of the impact on Okinawa, where U.S. Forces facilities and areas are concentrated, has been confirmed mutually by Japan and the U.S. on numerous occasions, including the Japan-U.S. summits, the “2+2” meetings, and the Japan-U.S. foreign ministerial meetings.

While continuing to work towards the realignment of U.S. Forces in Japan, Japan has been making its utmost efforts to make improvements in specific issues in light of the requests of local communities such as preventing incidents and accidents involving U.S. Forces, reducing the noise impact by U.S. Forces aircraft, and dealing with environmental issues at U.S. Forces facilities and areas in Japan.

As the current Japan-U.S. Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) does not include specific provisions on environment in December 2013, Japan and the U.S. concurred on launching bilateral consultations towards making a bilateral agreement that would supplement SOFA in the field of environment. Nine rounds of director-level negotiations were held since February 2014, and the two governments announced in the Japan-U.S. Joint Press Release in October 2014 that substantial agreement has been achieved on an Agreement on Cooperation in the Fields of Environmental Stewardship Relating to the United States Armed Forces in Japan, which would supplement SOFA (Environment Supplementary Agreement). The Environmental Supplementary Agreement was signed and enacted in September 2015. This Agreement explicitly includes provisions such as (1) the U.S. Government issuing and maintaining environmental governing standards that adopt the more protective of Japanese, U.S., or international agreement standards; (2) establishment and maintenance of procedures for Japanese authorities to have appropriate access following a contemporaneous environmental incident and for site surveys, including cultural asset surveys, associated with land returns. This Agreement is a legally binding international agreement and has a historical significance compared with conventional method of SOFA implementation improvement. Based on this Agreement, the Government of Japan will continue efforts towards achieving results on environmental measures at U.S. Forces facilities and areas.

(6) United Nations Command (UNC)and U.S. Forces in Japan

As the Korean War broke out in June 1950, UNC was established in July in the same year based on UN Security Council Resolution 83 and Resolution 84. Following the cease-fire agreement concluded in July 1953, UNC Headquarters was relocated to Seoul in July 1957, and UNC (Rear) was established in Japan. UNC (Rear)placed in Yokota Air Base currently has a stationed commander and three other staff and military attaches from eight countries1 who are stationed at embassies in Tokyo as liaison officers for UNC.

UNC may, based on Article 5 of the Agreement regarding the Status of the United Nations Forces in Japan, use the U.S. Forces facilities and areas in Japan to the minimum extent required to provide support for military logistics for UNC. At present, UNC is authorized to use the following seven facilities: Camp Zama, U.S. Fleet Activities, Yokosuka, U.S. Fleet Activities, Sasebo, Yokota Air Base, Kadena Air Base, Futenma Air Station, and White Beach Area.

- 1 Eight countries, consisting of Australia, UK, Canada, France, Turkey, New Zealand, the Philippines, and Thailand.