Diplomatic Bluebook 2015

Chapter 3

Japan’s Foreign Policy to Promote National and Worldwide Interests

4.Disarmament, Non-proliferation, and the Peaceful Use of Nuclear Energy

(1) General Overview

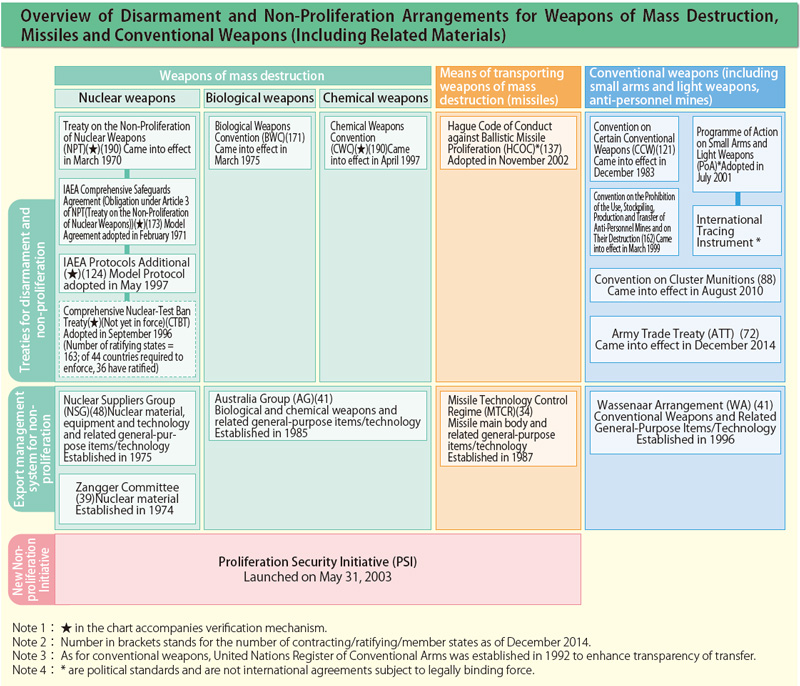

As a responsible member of the international community, Japan is striving to achieve disarmament and non-proliferation, both to ensure and maintain its own safety and to achieve a safe and peaceful world, based on the principle of pacifism advocated by the Constitution of Japan1. Japan’s efforts in this area encompass weapons of mass destruction (which generally refers to nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons), conventional weapons, missiles and other means of delivery, and related materials and technology.

As the only country to have ever suffered atomic bombings, Japan is engaged in various diplomatic efforts to achieve a world free of nuclear weapons. The Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) is the cornerstone of today’s international nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation regime. To maintain and strengthen the NPT regime, Japan has partnered with Australia to lead the Non-proliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI), a group consisting of 12 non-nuclear weapon States2, whose guiding policy is to promote realistic and practical proposals. Japan’s specific contributions include submitting working papers to the Preparatory Committees for the 2015 NPT Review Conference and issuing joint statements.

Japan’s endeavors also focus on achieving stronger, universal conventions targeting weapons of mass destruction, other than nuclear weapons, namely biological and chemical weapons, as well as those targeting conventional weapons.

In addition, Japan has endeavored to begin negotiations on new conventions, such as the Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty (FMCT) being discussed by the Geneva Conference on Disarmament (CD), as well as to enhance and increase the efficiency of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)3 safeguards4.

Japan is also actively involved in various international export control regimes, the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI)5, and initiatives aimed at enhancing nuclear security6.

Furthermore, Japan is actively engaging in disarmament and non-proliferation diplomacy through bilateral dialogue, undertaking wide-ranging activities that include promoting the peaceful uses of nuclear energy through the conclusion of bilateral nuclear cooperation agreements, as well as cooperation in achieving a safe nuclear energy life-cycle7.

- 1 For further details of Japan’s policy on nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation, see the 2013 white paper entitled “Japan’s Disarmament and Non-proliferation Policy (6th Edition)” (MOFA ed. http://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/gaiko/gun_hakusho/2013/index.html).

- 2 Established by Japan and Australia in September 2010, it now has 12 members; the other members are Canada, Chile, Germany, Poland, Mexico, the Netherlands, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, the Philippines, and Nigeria.

- 3 The IAEA was established in 1957 to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy and to prevent it from being diverted from peaceful to military uses. Its secretariat is located in Vienna. Its highest decision-making body is the General Conference, which consists of all member countries and meets once a year. The 35-member Board of Governors carries out the IAEA’s functions, subject to its responsibilities to the General Conference. As of December 2014, the IAEA has 162 member countries. Mr. Yukiya Amano has been its Director General since December 2009.

- 4 Verification measures (inspections, checks of each country’s material accountancy (management of its inventory of nuclear material) records, etc.) undertaken by the IAEA in accordance with the safeguards agreements concluded by each individual country and IAEA, in order to guarantee that nuclear material is being used solely for peaceful purposes and is not being diverted for use in nuclear weapons or the like. Pursuant to Article 3 of the NPT, the non-nuclear states that are contracting parties to the NPT are required to conclude safeguards agreements with the IAEA and to accept safeguards on all nuclear material within their borders (comprehensive safeguards).

- 5 Launched in May 2003, the PSI is an initiative aimed at implementing and examining measures that could be taken jointly within the scope of international law and the domestic laws of each country, in order to prevent the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and the like. As of December 2014, 104 countries were participating in or cooperating with the PSI’s activities. For hosting the PSI Maritime Interdiction Exercise in 2018, Japan actively participated in the Fortune Guard 2014 PSI interdiction exercise hosted by the US in August 2014 and took part in the Operational Experts Group (OEG) meeting hosted by the US in May.

- 6 Measures to prevent nuclear material and the like from falling into the hands of terrorists or other criminals.

- 7 Providing equipment required for the long-term storage on dry land of reactor compartments removed in the process of dismantling nuclear submarines (2012).

(2) Nuclear Disarmament

A. The Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT)

It is vital for all countries to steadily implement the Action Plan on concrete steps for the future of each of the three pillars of the NPT ((1) nuclear disarmament; (2) nuclear non-proliferation; and (3) peaceful uses of nuclear energy), which was agreed at the 2010 NPT Review Conference. The third session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2015 NPT Review Conference was held in New York in 2014. Although the Action Plan stipulated that the international conference on establishment of a Middle East zone free of nuclear weapons and all other weapons of mass destruction should take place in 2012, there was no prospect to set a date in 2014, and this remains an outstanding issue.

B. The Non-proliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI)

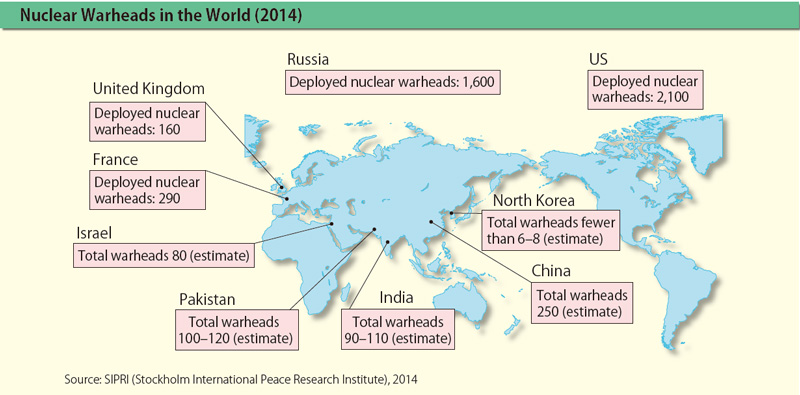

Through its realistic and practical proposals, and with the involvement of the foreign ministers of its member states, the NPDI serves as a bridge between nuclear and non-nuclear weapon states, taking the lead in the international community’s initiatives in the field of nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation. In April 2014, Japan hosted the 8th NPDI Ministerial Meeting in Hiroshima, for the first time in Japan. As well as being a chance for participants to witness with their own eyes the reality of atomic bombings, this meeting was a unique opportunity for NPDI member states to undertake more proactive discussions with a view to achieving a world free of nuclear weapons. Agreement was also reached on realistic and practical measures proposed by Japan, including the reduction of all types of nuclear weapons, the development of multilateral negotiations on nuclear disarmament, urging those not yet engaged in nuclear disarmament efforts to reduce their arsenals, and increased transparency. Furthermore, ahead of the 2015 NPT Review Conference, the NPDI members agreed to continue to cooperate in examining future strategies, in order to take the lead in the international community. In January 2014, prior to this ministerial meeting, Foreign Minister Kishida gave a speech in Nagasaki on Japan’s efforts toward nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation.

The Eighth NPDI Ministerial Meeting (April 11–12, Hiroshima)

The Eighth NPDI Ministerial Meeting (April 11–12, Hiroshima)

C. The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT)8

Japan regards the early entry into force of the CTBT as a priority, as it is a key pillar of nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation regimes. Accordingly, Japan is continuing its diplomatic efforts to this end, persuading those countries that have not yet ratified it to do so. Along with other members of the Friends of the CTBT group, Japan hosted the Seventh “Friends of the CTBT” Foreign Ministers’ Meeting at the UN Headquarters in September 2014.

D. The Treaty banning the production of fissile material for nuclear weapons or other fissile materials (Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty: FMCT)9

In 2012, in light of the fact that opposition by Pakistan had prevented the start of negotiations concerning the FMCT within the CD framework, the UN General Assembly decided to establish a Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on the FMCT. This GGE met again in 2014. Participating in the GGE as Japan’s governmental expert, former Ambassador of Japan to the Conference on Disarmament Akio Suda is contributing to discussions to ensure that deliberations in the GGE assist in advancing FMCT negotiations.

- 8 This prohibits all nuclear weapon test explosions and all other nuclear explosions everywhere, whether in outer space, in the atmosphere, underwater, and underground. Although it was opened for signature in 1996, it had not yet entered into force as of December 2014 because among the 44 countries whose ratification is required for the treaty to enter into force (Annex 2 States), China, Egypt, Iran, Israel, and the US have yet to ratify it, while India, North Korea, and Pakistan have yet to sign it.

- 9 A proposed treaty that seeks to halt the quantitative increase in nuclear weapons by prohibiting the production of fissile material (such as highly enriched uranium and plutonium) for use as raw material in the manufacture of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices.

E. Disarmament and Non-proliferation Education

In recent years, the international community has become increasingly aware of the importance of educating citizens about disarmament and non-proliferation, in order to further promote disarmament and non-proliferation efforts. As the only country to have ever suffered the devastation of atomic bombings during war, Japan is actively promoting disarmament and non-proliferation education. For example, Japan is translating the testimonies of atomic bomb survivors into other languages, conducting training courses for young diplomats from other countries in atomic bombed cities, and submitting working papers and giving speeches on this issue in the NPT Conference Review process. In addition, the Government of Japan supports activities aimed at conveying the reality of atomic bombing to people both within Japan and overseas. These activities include appointing atomic bomb survivors as “Special Communicators for a World without Nuclear Weapons” and having them speak at international conferences and the like about their experiences of the bombings. Furthermore, Japan provides cooperation when the UN Conference on Disarmament is held in Japan. In recent years, with the atomic bomb survivors growing older, Japan launched the “Youth Special Communicators for a World without Nuclear Weapons,” for the younger generation in addition to the existing “Special Communicators for a World without Nuclear Weapons”. Furthermore, Japan places high priority on intergenerational initiatives to pass on knowledge of the reality of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (see Special Feature on page 215 for further details).

F. Other Multilateral Initiatives

In September 2014, the UN General Assembly held an informal meeting to mark the International Day for the Total Elimination of Nuclear Weapons. Japan was represented at this meeting by Foreign Minister Kishida. In October, for the second consecutive year, Japan joined the two Joint Statements on the Humanitarian Consequences of Nuclear Weapons delivered by New Zealand and Australia respectively at the UN General Assembly’s First Committee. In addition, at the Third Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons, which took place in Vienna in December, participants from Japan included not only government representatives, but also experts and atomic bomb survivors. Every year since 1994, Japan has submitted a resolution on nuclear disarmament to the UN General Assembly. In December, at the 69th session of the UN General Assembly, this resolution was co-sponsored by 116 nations, the largest number ever, and was passed by an overwhelming majority, with 170 members voting in favor, 1 voting against (North Korea), and 14 abstaining.

G. Other Bilateral Initiatives

Through the Japan–Russia Committee on Cooperation for the Elimination of Nuclear Weapons Reduced in the Former Soviet Union, Japan has provided its cooperation to Russia in dismantling decommissioned nuclear submarines, with the objective of furthering nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation, as well as preventing environmental pollution10. Japan is also engaged in cooperation to enhance nuclear security through committees on cooperation for the elimination of nuclear weapons reduced in Ukraine and Kazakhstan, respectively11.

- 10 The “Star of Hope” program for the dismantling of decommissioned nuclear submarines was implemented as part of the G8 Global Partnership agreed at the 2002 Kananaskis G8 Summit (in Canada) and was completed in December 2009 after dismantling a total of six submarines. Since August 2010, Japan has undertaken cooperation through the construction of facilities for ensuring the safe onshore storage of reactor compartments removed from dismantled nuclear submarines. Japan is currently engaged in follow-up, including ex-post evaluation of the completed projects.

- 11 In January 2011, via the Japan–Ukraine Committee on Cooperation for the Elimination of Nuclear Weapons Reduced in Ukraine, Japan undertook efforts to enhance nuclear security at the Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology, while in November that year, Japan provided cooperation for the upgrading of protective materials and equipment to ensure nuclear security in Kazakhstan, via the Committee on Cooperation for the Destruction of Nuclear Weapons Reduced in the Republic of Kazakhstan. Japan is currently engaged in follow-up, including ex-post evaluation of the completed projects.

(3) Non-proliferation

A. Efforts to Prevent the Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction, etc.

Japan is undertaking various diplomatic efforts to enhance non-proliferation regimes. Firstly, as a member state of the IAEA Board of Governors designated by the Board12, Japan contributes to its activities in both personnel and financial terms. Regarding IAEA safeguards, which are central to international nuclear non-proliferation regimes, Japan encourages other countries to conclude Additional Protocols13 in cooperation with the IAEA, providing personnel and financial support for the IAEA’s regional seminars and using various discussion forums. Export control regimes are frameworks for cooperation among countries which have the ability to supply weapons of mass destruction, conventional weapons and/or related dual-use goods and technologies, and which have appropriate export controls. Japan participates in and contributes to all export control regimes relating to nuclear weapons, biological and chemical weapons, missiles14, and conventional weapons. In particular, the Permanent Mission of Japan to the International Organizations in Vienna serves as the Point of Contact of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG).

Moreover, as well as placing a high priority on the initiatives of the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI), Japan is utilizing frameworks such as the Asian Senior-level Talks on Non-proliferation (ASTOP)15 and the Asian Export Control Seminar16 to encourage other countries – primarily those in Asia – to enhance regional initiatives, with the aim of promoting understanding of non-proliferation regimes and enhancing relevant initiatives. Furthermore, through the International Science and Technology Center (ISTC), Japan is contributing to international scientific cooperation and efforts to prevent the proliferation of knowledge and skills in the field of weapons of mass destruction. More specifically, scientists from Russia and Central Asia, among others, who were previously involved in research and development focused on weapons of mass destruction and their delivery systems, are now employed by the ISTC, where they undertake research for peaceful purposes.

B. Regional Non-proliferation Issues

North Korea’s continued development of nuclear and missile program is a grave threat to the international peace and security; in particular, its nuclear program is a serious challenge to the global nuclear non-proliferation regime. In October 2002, the nuclear issue once again became more serious when North Korea admitted that it had a uranium enrichment program17. In 2007, ‘‘Initial Actions for the Implementation of the Joint Statement’’ and ‘‘Second-Phase Actions for the Implementation of the Joint Statement’’ were adopted at the Six-Party Talks. North Korea, however, soon announced the suspension of the actions prescribed in the two documents. Furthermore, in November 2010, North Korea showed a ‘‘uranium enrichment facility’’ to a Stanford University Professor, Siegfied Hecker, who visited North Korea.

North Korea proceeded with its third nuclear test in February 2013 and in April, it announced its intention to restart its nuclear facilities in Yongbyon.

In 2014, North Korea again launched ballistic missiles on several occasions. According to the IAEA Director General’s report published in September 2014, North Korea continues its nuclear and missile development with some signs, such as steam discharges associated with the graphite-moderated reactor and the expansion of the suspected facility for uranium enrichment. While continuing to coordinate closely with the US, the ROK and other relevant countries, Japan will strongly urge North Korea to steadily implement steps toward the abandonment of all nuclear weapons and existing nuclear programs, including immediate cessation of its uranium enrichment activities (see Chapter 2, Section 1, 1(1) ‘‘North Korea for details’’).

The Iranian nuclear issue is also a serious challenge to global nuclear non-proliferation regime. Since 2003, Iran had continued uranium enrichment-related activities, despite the adoption of a series of resolutions by the IAEA Board of Governors18 and UN Security Council resolutions calling for the suspension of such activities19. However, after the Rouhani administration took office in August 2013, Iran has changed its stand, and, in November 2013, an agreement that includes “elements of a first step”20 to be taken under Joint Plan of Action was reached. Under the “elements of a first step” to be taken under Joint Plan of Action, Iran agreed, among others, that it will not enrich uranium over 5%, it will dilute or convert 20% enriched uranium to 5%, and it will not make any further advances of its activity at Arak heavy-water reactor, in return for the partial lifting of sanctions by the EU3 (UK, France, and Germany) +3 (the US, China, and Russia). The negotiations toward a comprehensive resolution had continued but it had failed to reach an agreement and, in November 2014, the deadline for negotiation was extended to the end of June 2015.

Japan calls for peaceful and diplomatic solution to this issue. We will continue to be engaged with Iran based on traditionally friendly relations between our two countries while working closely with the US and other members of the EU3+3. When Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif visited Japan in March 2014, Foreign Minister Kishida urged Iran to cooperate fully with the IAEA in such areas as the ratification of the IAEA Additional Protocol. At the Japan-Iran Summit Meeting in September, Prime Minister Abe encouraged Iran to demonstrate flexibility in its negotiations with the EU3+3. In its relation with IAEA, although Iran has not been complying with the deadline for some measures to be taken concerning possible military dimensions (PMD)21, Japan will continue to urge Iran to fully cooperate with IAEA to resolve all outstanding issues.

With regard to Syria, in 2011, the IAEA Board of Governors found that the construction of an undeclared reactor at its Dair Alzour facility constituted a breach of its safeguards agreement with the IAEA. It is absolutely vital for Syria to cooperate fully with the IAEA and to sign, ratify, and implement an Additional Protocol in order to establish the facts.

- 12 Thirteen countries designated by the IAEA Board of Governors. Japan and countries such as other G8 members that are advanced in the field of nuclear energy are nominated.

- 13 Protocols concluded by each country with the IAEA, in addition to their Comprehensive Safeguards Agreements. The conclusion of Additional Protocols subjects countries to more stringent verification activities, extending the scope of information about nuclear activities that should be reported to the IAEA. As of December 2014, 124 countries have concluded such protocols.

- 14 In addition to export control regimes, the Hague Code of Conduct against Ballistic Missile Proliferation (HCOC) encompasses principles on self-restraint regarding the development and deployment of ballistic missiles. Japan served as the HCOC chair for a year from May 2013.

- 15 A multilateral forum hosted by Japan to discuss issues concerning the strengthening of non-proliferation regimes in Asia; the 10 ASEAN nations participate in these talks, along with China, the ROK, the US, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. The most recent meeting took place in January 2015.

- 16 A seminar to exchange views and information, aimed at strengthening export controls in Asia. It is attended by representatives of export control authorities from various countries and regions of Asia. Since 1993, it has been held annually in Tokyo, with 44 countries and regions participating in the February 2014 seminar.

- 17 In January 2003, North Korea gave notice of its withdrawal from the NPT and subsequently restarted its 5MW graphite-moderated reactor, which had been frozen under the Agreed Framework that the US and North Korea signed in October 1994; it also resumed the reprocessing of its spent nuclear fuel rods.

- 18 Following the resolution of the IAEA Board of Governors in September 2003 and the Tehran Declaration concluded with the EU-3 (UK, France, and Germany) in October, Iran demonstrated a constructive response for a time, committing to suspension of its enrichment-related activities and signing up to corrective measures concerning safeguards as well as signing of an Additional Protocol with the IAEA, but it continued its activities associated with uranium enrichment.

- 19 Series of UN Security Council resolutions have been passed regarding the Iranian nuclear issue. These resolutions oblige Iran to halt all enrichment-related and reprocessing activities, as well as its heavy water reactor program, under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations, and to provide IAEA with relevant access and cooperation to resolve all outstanding issues. In addition, they call on Iran to promptly ratify an Additional Protocol, and Resolution 1835 calls on Iran to comply with the obligations under these four resolutions without delay. Resolutions 1737, 1747, and 1803 contain measures against Iran under Chapter VII, Article 41 of the Charter, including an embargo on the supply of nuclear-related materials to Iran and the freezing of the assets of individuals and organizations related to Iran’s nuclear or missile programs. Resolution 1929 includes comprehensive measures such as an expansion of the arms embargo, restrictions on ballistic missile development, an extension of the scope of the asset freeze and travel ban, the strengthening of restrictions targeting the financial, commercial, and banking sectors, and cargo inspections as the additional measures against Iran.

- 20 [Elements of a first step]

<Iran’s voluntary measures >- Suspension of uranium enrichment over 5%

- Dilute the 20% UF6 to no more than 5% and convert UF6 enriched

- Suspending the strengthening of enrichment capacity (No new location for the enrichment. No additional centrifuges.)

- Ban on increasing stockpiles of low enriched uranium

- Iran announces that it will not make further advances of its activities at the Arak reactor

- Enhanced monitoring by IAEA

- <EU3+3’s voluntary measures >

- Limited, temporary, targeted, and reversible lifting of sanctions

- Suspension of sanctions on gold and precious metals, and the petrochemical and auto industry

- Suspension of sanctions in the civil aviation sector (supply of repair parts needed for safety reasons)

- Maintenance of imports of crude oil produced in Iran at the current, substantially reduced level.

- Postponement for six months of the imposition of new sanctions against the nuclear program

- Facilitation of humanitarian transactions and establishment of a financial channel

- [Elements of the final step of a comprehensive solution]

- Comprehensive lifting of UN Security Council, unilateral or multilateral sanctions in the nuclear field

- A mutually agreed enrichment program (mutually agreed parameters consistent with practical-needs, with agreed limits on scope and level of enrichment activities, capacity, where it is carried out, and stocks of enriched uranium, for period to be agreed upon.)

- Fully resolve concerns related to the reactor at Arak. No reprocessing or construction of a facility capable of reprocessing

- Fully implement the agreed transparency measures and enhanced monitoring. Ratify and implement the Additional Protocol.

- Include international civil nuclear cooperation, including among others, on acquiring modern light water power and research reactors and associated equipment, and the supply of modern nuclear fuel.

- Following successful implementation of the final step of the comprehensive solution for its full duration, the Iranian nuclear programme will be treated in the same manner as that of any non-nuclear weapon state party to the NPT.

- 21 PMD (Possible Military Dimensions)

In November 2011, a report by the Director General of the IAEA pointed out “possible military dimensions” of Iran’s nuclear program, which consists of twelve indicators. It has been treated as a key issue in consultations between Iran and the IAEA.

(4) Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy

A. Multilateral Initiatives

A growing number of countries are seeking to expand nuclear power generation or to introduce it, due to such factors as growing global energy demand and the need to address global warming. Even after the accident at Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station (TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi NPS), nuclear power remains an important source of energy for the international community.

However, the technology, equipment, and nuclear material used for nuclear power generation can be diverted to military uses. A nuclear accident in one country may have a wide-scale impact on its neighboring countries. For these reasons, in the peaceful uses of nuclear energy, it is vital to ensure the 3S’s: (1) Safeguards (and other non-proliferation measures); (2) Safety (ensuring nuclear safety to prevent a nuclear accident, etc.); and (3) Security (measures against nuclear terrorism). Japan has been undertaking diplomacy through bilateral and multilateral frameworks with the aim of establishing a common understanding among the international community on the importance of the 3S’s.

It is Japan’sresponsibility to share with the rest of the world its experience and lessons learned from the accident at TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi NPS, in order to strengthen global nuclear safety. From this perspective, Japan and the IAEA held workshops in April and November 2014 at the IAEA Response and Assistance Network (RANET) Capacity Building Centre (CBC), which was designated in Fukushima Prefecture. These workshops provided relevant Japanese and foreign participants with training in emergency preparedness and response. It is vital to provide not only to the Japanese public, but also to the international community information on the situation at Fukushima Daiichi NPS in a timely and appropriate manner. Japan issues comprehensive reports via the IAEA, which includes information on the progress of decommissioning and countermeasures against contaminated water of Fukushima Daiichi NPS, the results of monitoring of the air dose and radioactivity concentration in the ocean and food safety. Japan also holds briefing sessions for the diplomatic corps in Tokyo and provides information via diplomatic missions overseas.

The decommissioning of the reactors at Fukushima Daiichi NPS, including efforts to deal with the issue of contaminated water, involves a series of complex tasks without precedent anywhere in the world. Japan is gathering technologies and knowledge not only from domestic experts, but also from the IAEA and the international community to resolve this issue. For this purpose, Japan accepted marine monitoring experts from the IAEA in September and November 2014. Japan is also engaging in partnership and cooperation with the international community regarding effects of radiation. In September and November 2014, the UN Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) held seminars and workshops in Fukushima Prefecture as well as in Tokyo.

Given that Japan prioritizes promotion of the peaceful uses of nuclear energy especially in developing countries, Japan contributes to the IAEA’s Technical Cooperation Fund and provides support via the IAEA’s Peaceful Uses Initiative (PUI). Japan attaches particular importance to non-power applications of nuclear science and technology, such as in the field of human health and agriculture. In the field of energy production, Japan provides assistance such as enhancement of radiation protection. Japan is contributing to the socioeconomic development of developing countries by promoting the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. With regard to nuclear liability, following the Diet’s approval in November 2014, Japan concluded the Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage (CSC) in January 2015. The CSC will contribute to prompt and fair remedies for victims, increase in compensation capacity and enhancement of the legal predictability. As a result of Japan’s conclusion, the CSC entered into force on April 15, 2015, marking a step toward establishing a global nuclear liability regime.

B. Bilateral Nuclear Cooperation Agreements

Bilateral nuclear cooperation agreements are concluded to secure a legal assurance from the recipient country, when transferring nuclear-related materials and equipment such as nuclear reactors to that country, that they will be used only for peaceful purposes. The agreements especially aim to promote the peaceful uses of nuclear energy and ensure nuclear non-proliferation.

Moreover, as Japan attaches importance to the 3S’s, the recently concluded agreements between Japan and a third country include provisions regarding nuclear safety. Through implementing such agreements, cooperation in the area of nuclear safety can be promoted.

Even after the accident at TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi NPS, high expectation for Japan’s nuclear technology has been expressed by numerous countries. It is Japan’s responsibility to share with the rest of the world its experience and lessons learned from the accident, in order to strengthen international nuclear safety. Based on this recognition, in its bilateral nuclear energy cooperation, Japan intends to provide nuclear-related materials, equipment, and technology with the world’s highest safety standards, while taking into account the situation in and intention of countries desiring to cooperate with Japan in this field. Accordingly, when considering whether or not to establish a nuclear cooperation agreement framework with a third country, Japan considers the overall situation in each individual case, taking into account such factors as nuclear non-proliferation, nuclear energy policy in that country, that country’s trust in and expectations for Japan, and the bilateral relationship between them.

As of the end of 2014, Japan has 14 concluded nuclear cooperation agreements with the US, the UK, Canada, Australia, France, China, the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM), Kazakhstan, the Republic of Korea, Vietnam, Jordan, Russia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates.

C. Nuclear Security

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union and the 9.11 terrorist attacks in the US brought heightened attention to physical protection of nuclear materials, international cooperation to prevent terrorist activities using nuclear material or other radioactive material has intensified, through initiatives by the IAEA and the UN, as well as voluntary initiatives by various countries.

In particular, the third meeting of the Nuclear Security Summit, a series of meetings initiated by the U.S. President Obama took place in The Hague, the Netherlands, in March 2014, attended by 53 countries and four international organizations. Prime Minister Abe participated in this summit (for details, see the Special Feature on page. 214).

In June, the Diet gave its approval to the Government of Japan to accept the “Amendment to the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material,” and the Instrument of Acceptance was deposited to the IAEA.

(5) Biological and Chemical Weapons

A. Biological Weapons

The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC)22 is the only multilateral legal framework imposing a comprehensive ban on the development, production, and retention of biological weapons. However, the question of how to enhance the convention is a challenge, as it contains no provision regarding the means of verifying compliance with the BWC.

In 2014, a Meeting of Experts was held in August, followed by a Meeting of States Parties in December. At the Meeting of Experts, Japan contributed to discussions on strengthening the convention, with a presentation by a Japanese expert on such matters as the legal system regarding bio risk management measures, efforts to address dual-use research in biotechnology and biological agents, which could be exploited or misused for purposes other than their original purpose and issues to be addressed in the future.

- 22 Entered into force in March 1975. There are 171 States Parties to the convention (as of December 2014).

B. Chemical Weapons

The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC)23 imposes a comprehensive ban on the development, production, retention, and use of chemical weapons and stipulates that all existing chemical weapons must be destroyed. Compliance with this groundbreaking international agreement on the disarmament and non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction is ensured through a system of verification (declaration and inspection). The implementing agency of the CWC is the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), which is based in The Hague (the Netherlands). Along with the UN, the OPCW has played a key role in the destruction of Syria’s chemical weapons, which has been underway since September 2013, and Japan has provided financial support for these activities.

Japan is actively involved in cooperation aimed at increasing the number of member countries, efforts by States Parties to strengthen measures for national implementation of the convention in order to increase its effectiveness, and international cooperation to this end. In August 2014, Japan dispatched an expert to participate in a mock inspection as part of the OPCW’s activities to encourage ratification of the CWC by Myanmar. In September, as part of an OPCW program, Japan hosted two trainees from Malaysia and Bhutan at Japanese chemical plants, where they underwent training in plant safety management.

Moreover, under the CWC, Japan has an obligation to destroy chemical weapons abandoned by the Imperial Japanese Army in China, as well as it destroys old chemical weapons within Japan. As such, working in cooperation with China, Japan makes its utmost effort to complete the destruction of these weapons as soon as possible. In March 2014, during talks with OPCW Director-General Ahmet Üzümcü, Prime Minister Abe expressed that Japan would continue to do its utmost to complete the destruction of these weapons as soon as possible, in cooperation with China.

- 23 Entered into force in April 1997. There are 190 States Parties to the convention (as of December 2014).

(6) Conventional Weapons

A. Cluster Munitions24

Japan takes the humanitarian consequences of cluster munitions very seriously. Therefore, in addition to taking steps to address these weapons by supporting victims and unexploded ordnance (UXO) clearance, Japan is continuing its efforts aimed at increasing the number of States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM)25. Moreover, Japan is assisting with UXO clearance bomb disposal and victim support projects in Laos, Lebanon and other countries that have suffered harm from cluster munitions26.

B. Small Arms and Light Weapons

Sometimes called the real weapons of mass destruction because of the huge number of deaths that they have caused, small arms and light weapons continue to proliferate, due to their ease of operation. The use of small arms and light weapons is believed to result in the deaths of at least half a million people each year, and they prolong and escalate conflict, while hindering the restoration of public security and post-conflict reconstruction and development. In addition to contributing to efforts within the UN, such as the annual submission to the UN General Assembly of a resolution on small arms and light weapons, Japan supports various programs to combat small arms and light weapons across the globe, including weapons recovery and disposal programs and training courses.

C. Anti-Personnel Mines

Japan promotes comprehensive initiatives focused primarily on the effective prohibition of anti-personnel mines and strengthening support for countries dealing with the consequences of land mines located within their own borders. As well as calling on countries in the Asia-Pacific region to ratify the Convention on the Prohibition of Anti-Personnel Mines (Ottawa Treaty)27, Japan has, since 1998, provided support worth over 58 billion yen to 50 countries and regions, including funding for south-south cooperation, to assist them in dealing with the consequences of land mines (for example, land mine removal and support for the victims of land mines).

In June 2014, the Third Review Conference of the Ottawa Convention was held in Mozambique. Along with a number of other outcome documents, the Maputo Action Plan was adopted at the conference. This plan describes the specific actions that the States Parties should continue to take over the next five years in such fields as the destruction of stockpiled land mines, the clearance of buried land mines, and support for land mine victims. Along with Mozambique, Japan served as co-chair of the Standing Committee on Mine Clearance at the conference’s session on mine clearance. In addition, Japan is currently serving a term (running from January 2014 until December 2015) as chair of the Mine Action Support Group, which consists of major donor states that support efforts to combat land mines.

D. The Arms Trade Treaty (ATT)

The ATT28 seeks to establish common international standards to regulate international trade in conventional weapons and prevent illegal trade in them. The ATT was adopted at the UN General Assembly in April 2013 and became effective on December 24, 2014, after the 50th instrument of ratification was deposited in September 2014, enabling the Treaty to enter into force. Consistently asserting the need for participation by an effective and wide-ranging array of countries, Japan has played a proactive and constructive role as one of the original co-sponsors of the resolution that began the ATT process. In May, Japan deposited the instrument of acceptance, becoming the first States Party in the Asia-Pacific region, and is calling on nations that have not yet ratified the Treaty to do so without delay.

- 24 In general, this refers to bombs and shells that take the form of a large container with numerous bomblets inside, which breaks open at altitude, dispersing the bomblets over a wide area. They are said to have a high probability of becoming unexploded ordnance, giving rise to the problem of accidental explosions that cause civilian casualties.

- 25 As well as prohibiting the use, possession, and manufacture of cluster munitions, the Convention, which entered into force in August 2010, obliges states that have joined it to destroy stockpiled cluster munitions and to remove cluster munitions from areas contaminated by them. Including Japan, there were 86 States Parties as of December 2014.

- 26 For details of specific international cooperation initiatives to combat cluster munitions and anti-personnel mines, see the Official Development Assistance (ODA) White Paper (http://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/gaiko/oda/index.html).

- 27 As well as prohibiting the use and production of anti-personnel mines, the Convention, which entered into force in March 1999, obliges states that have joined it to destroy stockpiled land mines and to remove buried land mines. Including Japan, there were 162 States Parties as of December 2014.

1. About the Nuclear Security Summit

Group photo of Nuclear Security Summit in The Hague (The Hague, March 24–25; Source: Cabinet Public Relations Office)

Group photo of Nuclear Security Summit in The Hague (The Hague, March 24–25; Source: Cabinet Public Relations Office)

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe attended the Nuclear Security Summit in The Hague on March 24 and 25, 2014. The purpose of the Nuclear Security Summit is to have a top-level discussion on nuclear terrorism, which has posed an immediate threat to global security. The first summit took place in April 2010 at the initiative of President Obama of the United States.

53 countries and 4 international organizations attended this third summit, including the leaders of 31 countries. This is a rare opportunity that brings such a large number of leaders together, reflecting the importance of the summit.

2. Features of the Summit

The summit reflected the intention of the Netherlands, the host country, which was to focus on dialogue more than just read out the official statement of each country. During the summit, the policy, discussion on anti-nuclear-terrorism measures based on fictional scenarios, and a high-level informal discussion on the future of the summit without personnel accompanied, were newly convened.

3. Outcomes

Active high-level discussions took place during the summit. Particularly several countries including Japan presented their concrete measures for minimizing nuclear material and many countries emphasized acceleration of efforts towards prompt entry into force of the Amendment to the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material and the importance of the role of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). At the end of the summit, the Hague Communiqué was adopted on the basis of these arguments.

4. Presentations by Japan

The conference room

The conference room

Japan published a video message from Prime Minister Abe, introducing measures for enhancing nuclear security, on the official website for the summit and released the Joint Statement by the Leaders of Japan and the United States on Contributions to Global Minimization of Nuclear Material on the occasion of the summit. Japan also announced its enhancement of efforts towards concluding the Amendment to the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material and released the Joint Statement on Transportation Security by the five participating states led by Japan. Japan concluded the amendment after the summit in June 2014.

5. Towards the next summit

Japan does its best to enhance nuclear security domestically and internationally in order to globally promote nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament towards the total elimination of nuclear weapons. These efforts reflect Japan’s policy of “Proactive Contribution to Peace”. Japan will continue to enhance nuclear security towards the next summit.

Group photo of the High School Student Peace Ambassadors (27 April, Hiroshima)

Group photo of the High School Student Peace Ambassadors (27 April, Hiroshima)

The author engaged in a relay talk

The author engaged in a relay talk

Toward a Peaceful World free of Nuclear Weapons!

This year, 20 high school students departed for Switzerland once again, to add our threads of passion and aspirations to the fabric of peace that High School Student Peace Ambassadors have continued to weave over the past 16 years.

The history of High School Student Peace Ambassadors began in 1998, triggered by the desire to spread across the world the voices of youth from areas that had suffered from atomic bombings. This year, the initiative saw a record high of 500 applicants, out of which only 20 Peace Ambassadors were selected. We, the 17th generation of High School Student Peace Ambassadors, have been designated as “Youth Communicators for a World without Nuclear Weapons” by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. For six days from 16 to 22 August, we visited the UN headquarters in Europe, the UNI Global Union, and World YWCA, and presented speeches about our thoughts on peace.

At UNI and YWCA, staff of various nationalities told us that they were inspired to see high school students travelling the world to engage actively in peace activities, and expressed their hope to create a peaceful future together.

After that, we visited the UN headquarters in Europe. This visit was a special event, as Ms. Masaki Koyanagi, a second year student from Kwassui Senior High School in Nagasaki, represented our delegation and was the first non-governmental representative to issue a statement at the Conference on Disarmament. This provided a great stimulus to the conference, which has been in deadlock in recent years. The event also received major coverage in Japan. This was the result of the foundation that past generations of Peace Ambassadors had built, and despite being a small step forward, it gave us a renewed sense that putting in steady effort without giving up could bring us this far. Ms. Koyanagi’s speech described the thoughts and desires of all the Peace Ambassadors. She implored everyone not to forget the tragedy that took place 69 years ago, spoke of her determination as a third-generation victim of atomic bombings to pass down the truth about the bombing to future generations, and said that the youth of Japan, including ourselves, have the responsibility to call for the abolition of nuclear weapons.

After the Conference, the delegation met with Thomas Markram, Deputy Secretary-General of the Conference on Disarmament. After listening to our speech, he encouraged us to “Never give up,” saying that although a world free of nuclear weapons was difficult to achieve, grass-root level campaigns such as ours could exert great power, and that our future was in our own hands.

On this journey, we encountered many people who listened to the voices of the young and lended us their support, as well as others who had high expectations of us. We will never stop striding ahead as long as there are such people in the world. We aim to take yet another new step forward, so that we can pass on a peaceful world to future generations.

Yuri Nakamura,

17th Generation of High School Student Peace Ambassadors