3. Efforts for Strengthening Partnerships

As Japan’s development cooperation is carried out in partnership with diverse actors, a variety of institutional reforms and other improvements are made to maximize its effects. For development cooperation implemented by the government and its associated agencies, the government strives to strengthen collaboration between JICA and other agencies responsible for official funds such as the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC), Nippon Export and Investment Insurance (NEXI), Japan Overseas Infrastructure Investment Corporation for Transport and Urban Development (JOIN), and the Fund Corporation for the Overseas Development of Japan’s ICT and Postal Services (Japan ICT Fund). In addition, the government also endeavors to enhance mutually beneficial partnerships with various actors so as to serve as a catalyst for mobilizing and assembling a wide range of resources, including the private sector.

Furthermore, in order to ensure that a wide range of relevant organizations and people cooperate to promote Japan’s efforts to implement the 2030 Agenda adopted in the United Nations Summit in September 2015, Japan established the SDGs Promotion Roundtable Meetings, consisting of governments, NGOs/NPOs, academia, the private sector, international organizations, and various groups, which holds exchanges of views and promotes partnership among a variety of stakeholders.

(1) Public-Private Partnership (PPP)

With the globalization of the economy, the inflow of private finance into developing countries is currently about 2.5 times larger than that of ODA. Therefore, it is increasingly important to promote the contribution of private finance to development to address the financing needs of developing countries. In response to such a situation, the Government of Japan promotes quality infrastructure investment by way of Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) as mentioned earlier (see this), and in other sectors, Japan encourages private investments through the following PPP measures.

Various operations conducted by Japanese private companies in developing countries can yield a range of benefits to these countries by creating local employment opportunities, augmenting tax revenue, expanding trade and investment, contributing to the acquisition of foreign currency, and transferring Japan’s high-standard technology. Aiming to facilitate activities by these private companies in developing countries, in April 2008, the government announced the Public-Private Partnership for Growth in Developing Countries, a new policy to strengthen partnerships between official funds, such as ODA, and Japanese companies. Accordingly, the government accepts consultations and proposals from private companies regarding PPP projects in which the activities of the private companies conducive to economic growth and poverty reduction in developing countries are coordinated with ODA. For example, Japan invited people from the electricity industry in Viet Nam to Japan to teach them about Japan’s safe and efficient electricity distribution engineering technologies, including the hot line method. (Note 3)

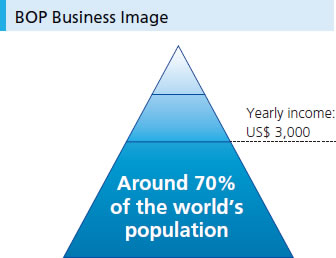

Meanwhile, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) activities and Base of the Economic Pyramid (BOP) businesses* have been drawing increasing attention in recent years. CSR activities conducted by private companies are aimed at proactive contribution to solving the issues within local societies in which they operate. In addition, BOP businesses are targeting the base of the economic pyramid, and are expected to contribute to improving livelihoods and solving social issues. In order to promote cooperation between the CSR activities and/or BOP businesses of Japanese private companies and the activities of local NGOs and other organizations, preferred slots were created within Grant Assistance for Grass-Roots Human Security Projects.* Japan also actively supports cooperation within the nonpublic sectors and authorized 21 such projects in FY2015.

In addition, Japan carries out PPP* that aims to implement highly public nature projects more efficiently and effectively through public-private cooperation. Japan provides assistance from the planning stage to the implementation of a project, such as institutional development and human resources development through technical cooperation, as well as utilizing Private-Sector Investment Finance and ODA loans.

Furthermore, international organizations, such as UNDP and UNICEF, promote inclusive businesses* by Japanese companies on the basis of the organizations’ extensive experience and expertise in developing countries. For example, the UNDP utilized the Japan-UNDP Partnership Fund to support the production and marketing of traditional products in Bhutan. It also considered selling those products in Japan through Japanese companies participating in the Business Call to Action (BCtA), an international initiative that encourages businesses that simultaneously achieve corporate profits and development objectives.

A. Preparatory surveys for PPP infrastructure projects and BOP business promotion

JICA implements two types of preparatory survey based on proposals from private companies to encourage Japanese companies with advanced technologies, knowledge and experience and have an interest in overseas expansion to participate in the field of development. In detail, this is a survey scheme based on proposals from private companies to assist the formulation of their project plans. JICA calls for a wide range of proposals from private companies for a feasibility survey* on PPP infrastructure projects and BOP business promotion, respectively, and entrusts feasibility surveys to the companies that have submitted such proposals. So far, JICA has selected 69 PPP infrastructure project proposals such as water and sewerage system and motorway projects, and 107 BOP business promotion proposals in the areas of health and medical care and agriculture. Following the preparatory surveys for PPP infrastructure projects, some of these projects were authorized as Private-Sector Investment Finance projects. Through this scheme, JICA will utilize the expertise, funds, and technologies of private companies for the socioeconomic development of developing countries and will support the overseas expansion of private companies.

B. Partnership with Japanese small and mediumsized enterprises (SMEs) and other entities

Giving a lecture on the use of a mobile CTG to midwives and obstetriciangynecologists at a healthcare center in the Republic of South Africa (Photo: MITLA Corporation)

Incorporating the rapid economic growth of emerging and developing countries is of crucial importance for the future growth of the Japanese economy. In particular, although Japanese SMEs possess numerous world-class products and technologies, many businesses have been unable to take steps for overseas business expansion due to insufficient human resources, knowledge, or experience. On the other hand, it is expected that such products and technologies of Japanese SMEs and other entities will be useful for the socio-economic development in developing countries.

In response to these circumstances, MOFA and JICA proactively support the overseas business expansion of Japanese SMEs and other entities using ODA. Specific examples include: a survey for collecting basic information and formulating project plans necessary for the overseas business of an SME or other entities that contribute to resolving the issues of developing countries (Promotion Survey); surveys for studying the feasibility of using an SME’s or other entities’ product or technology in a developing country, based on their proposals (Feasibility Survey with the Private Sector for Utilizing Japanese Technologies in ODA Projects); and surveys to verify ways to enhance a product or technology’s compatibility with a developing country and to disseminate them, based on a proposal from an SME or other entities (Verification Survey with the Private Sector for Disseminating Japanese Technologies).

These projects aim to achieve both the development of developing countries and the vitalization of the Japanese economy by utilizing Japanese SMEs’ and other entities’ excellent products and technologies. From FY2012 to FY2015, MOFA and JICA supported 396 SMEs’ surveys and Verification Surveys. As a result, out of the 135 projects for which Promotion Surveys, Product Feasibility Surveys, and Verification Surveys have been completed before September 2015, 78% (106 projects) have ongoing overseas activities in the relevant countries.

As participating companies, business organizations and others have expressed many requests for further expansion of such efforts. Japan continues to proactively support the overseas business expansion of SMEs and other entities through ODA.

Furthermore, Japan provides grant aid (provision of equipment using SMEs’ products) for this purpose. By providing Japanese SMEs’ products based on the requests and development needs of developing country governments, Japan not only supports the socio-economic development of developing countries, but also supports the overseas business expansion of Japanese SMEs by raising the profile of the SMEs’ products and creating sustained demand for them.

In addition, in order to assist the development of global human resources required by SMEs and other entities, the “Private-Sector Partnership Volunteer System”* in which employees from companies are dispatched to developing countries as Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers (JOCV) or Senior Volunteers (SV) while keeping their affiliation with their companies was established in 2012. Through this system, Japan proactively supports companies to expand their businesses overseas.

Similarly, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) supports human resources development by accepting trainees for training in Japan and dispatching experts overseas, in order to develop the local human resources that will be an issue in the overseas expansion of Japan’s SMEs. Furthermore, through the Global Internship Program to dispatch young business persons METI is working on development of the global human resources that will be responsible for the overseas expansion of the SMEs.

C. Grant aid for business/management rights

In FY2014, Japan introduced grant aid for business/ management rights. By extending grant aid for public works projects that comprehensively implement the continuum of activities from facility construction to operation, maintenance and management with the involvement of private companies, this grant aid aims to facilitate the acquisition of business and management rights by Japanese companies and utilize Japan’s advanced technologies and know-how for the development of developing countries. This grant aid was provided for a project to address water leakages in Myanmar and a project to address medical waste in Kenya by FY2016 (as of February).

D. Improving Japan’s ODA Loans

ODA loans are expected to provide Japan’s advanced technologies and know-how to developing countries, and thereby improve people’s living standards. At the same time, Japan seeks to use ODA loans to tap into the growth of emerging economies, including those in Asia, which have particularly close relationships with Japan, and contribute to the vitalization of the Japanese economy. In this regard, Japan will carry out further improvement of Japan’s ODA loans to make them even more attractive to both developing countries and Japanese private companies.

Japan announced “Improvement Measures for the Strategic Use of ODA Loans” and other institutional improvements in April and October 2013. First, in April, former priority areas were re-categorized into either “environment” or “human resources development,” and “disaster prevention and reduction” and “health and medical care and services” were added as new priority areas. Additionally, improvements were made to the Special Terms for Economic Partnership (STEP) scheme that was introduced to promote “Visible Japanese Assistance” by utilizing Japan’s advanced technologies and know-how as well as transferring technologies to developing countries. These improvements include expanding the scope of application of STEP and lowering interest rates. At the same time, Japan has been taking additional measures such as the establishment of the Stand-by Emergency Credit for Urgent Recovery (SECURE). (Note 4) Japan has also decided to make further use of ODA loans for developing countries that have income levels equal to or higher than those of middle-income countries. Moreover, in October, Japan introduced the Equity Back Finance (EBF) loan (Note 5) and the Viability Gap Funding (VGF) loan. (Note 6) These instruments are designed to support, as needed, the development and application of effective measures to promote the steady formulation and implementation of PPP infrastructure projects by recipient governments.

In June 2014, Japan decided to utilize the “Sector Project Loan” that provides Japan’s ODA loans comprehensively for multiple projects of the same sector, etc. in a fullfledged manner. Japan also decided to further accelerate the implementation of Japan’s ODA loans by integrating the pre-qualification with project tender processes for Japan’s ODA loan projects when Japanese companies’ engagement is expected. In November 2014, Japan decided to introduce the Contingent Credit Enhancement Facility for PPP Infrastructure Development (CCEF-PPP). (Note 7)

In November 2015, Japan announced follow-up measures of the Partnership for Quality Infrastructure (Note 8) that would improve Japan’s ODA loans and Private-Sector Investment Finance (PSIF)* by accelerating Japan’s ODA loan procedures and creating a new ODA loan scheme, among other measures. Specifically, the following measures are included: the government would reduce the period necessary for government-related procedures for Japan’s ODA loans that normally require three years to approximately one and a half years at most for important projects and to approximately two years at most for other projects; on the condition that JICA’s financial grounds are ensured, the government would introduce ODA loans with currency conversion option to countries that have income levels equal to or higher than those of middle-income countries as well as establish dollardenominated forms of Japan’s ODA loans, Preferential Terms for High Specification, and Japan’s ODA loans for business/management rights; the government would add “special contingency reserves” in the amount to be committed in Exchange of Notes (E/N); and in providing Japan’s ODA loans directly to sub-sovereign entities such as local governments and public corporations of developing countries, the government decided to exempt the Government of Japan guarantee as an exception on a case-by-case basis at a ministerial conference if various conditions, including economic stability of recipient countries and sufficient commitment by recipient governments, are met. In addition, the measures set forth that pilot/test-marketing projects would be conducted through grant aid, etc. In May 2016 in the Expanded Partnership for Quality Infrastructure, (Note 9) Japan announced the further acceleration of Japan’s ODA loan procedures, and decided to streamline the period between the initiation of the project feasibility study (F/S) and commencement of the construction work to one and a half years at the fastest and aim for increased “visibility” of the approximate term necessary for respective procedures.

E. Private-Sector Investment Finance

Private financial institutions are often reluctant to finance projects by private companies in developing countries for reasons including the high risk involved. Considering such a situation, Japan uses JICA’s PSIF to directly invest in and provide loans for, and thereby assist the development projects by private companies in developing countries.

The Reorganization and Rationalization Plan for Special Public Corporations announced in December 2001 stipulated that, in principle, no PSIF investments and loans would be made, except for projects authorized before the end of FY2001. However, due to the increased need to respond to new demand for funds for implementing high development impact projects through private sector engagement, JICA resumed the provision of PSIF to private companies on a pilot basis. For example, PSIF has been provided for an industrial human resources development project in Viet Nam and a microfinance project for the poor in Pakistan since March 2011.

JICA fully resumed PSIF in October 2012. As of the end of 2016, a total of 14 investment and loan agreements have been signed, including the Thilawa Special Economic Zone (Class A Area) Development Project in Myanmar. In order to reduce the exchange rate risk of companies participating in infrastructure projects, JICA announced in succession the introduction of local currency-denominated PSIF (June 2014) and U.S. dollar-denominated PSIF (June 2015) for the PSIF scheme to supplement the existing yendenominated PSIF.

Next, in November 2015 Japan announced follow-up measures of the Partnership for Quality Infrastructure that included acceleration of PSIF, expansion of the coverage of PSIF, and strengthening of the collaboration between JICA and other organizations. The measures set out that JICA would start its appraisal process, in principle, within one month after an application was filed by private companies, etc., that the standard period for JBIC to respond to inquiries on projects was to be two weeks, that the government was to enable JICA to co-finance with private financial institutions, and that the government would review the requirement of the “no-precedent policy” and allow loans to be provided in cases where non-concessional loans by existing Japanese private financial institutions were impossible.

In May 2016 in the Expanded Partnership for Quality Infrastructure, Japan decided to consider accommodating regulations on the largest share of equity allowed, such as the expansion of JICA’s share of equity from 25% to 50% (the percentage should not make JICA the largest shareholder) for flexible operation and review of JICA PSIF, and to consider the possibility of Euro-denominated PSIF.

F. Collaboration Program with the Private Sector for Disseminating Japanese Technology for the Social and Economic Development of Developing Countries

This private sector proposal-type program aims to deepen the understanding of excellent products, technologies, and systems of Japanese companies, as well as to examine the feasibility of their application to the development of developing countries, through training in Japan and locallyheld seminars aimed primarily at government officials from developing countries. JICA calls for proposals from private companies, and the implementation of selected projects is entrusted to the companies that make the proposals. As a result, the projects and the private companies’ subsequent execution of the projects contribute to resolving the challenges of developing countries. At the same time, private companies can expect positive effects such as increased awareness of their company’s technologies, products, and systems in the relevant country, detailed execution of businesses of a highly public nature, and networking with government officials in developing countries.

In FY2016, ten proposals were selected (of which four were selected for the “health and medical care special category” and “infrastructure system export special category” of the FY2016 supplementary budget, respectively). The proposals covered a wide range of sectors including health and medical care, transportation, energy, disaster risk reduction, and environmental management that make use of Japan’s technologies and know-how, as well as new sectors such as space development that utilizes infrastructure technologies. The proposals targeted mainly Southeast Asia but also extended over a broad geographical area including South Asia, Central Asia, Middle East, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Africa.

- * BOP (Base of the Economic Pyramid) business

- BOP refers to businesses that are expected to be useful in resolving social issues for low-income groups* in developing countries. Accounting for approximately 70% of the world’s population, or approximately 5 billion people, low-income groups are attracting attention as a market with potential for growth. It is expected that incorporating low-income groups into consumption, production, sales, and other value chains will be useful in providing sustainable solutions to a variety of local societal problems. Examples: models that aim to improve nutrition through sales to the poor of nutrientenhanced food for infants, models that aim to increase incomes by improving crop yields and quality through technical support related to high-quality mung bean cultivation for poor farmers, etc.

* Low-income group: The income bracket with an annual income per capita of $3,000 or less in purchasing power parity. Purchasing power parity is determined by removing differences between price levels to make purchasing power between different currencies equivalent. - * Grant Assistance for Grass-Roots Human Security

- This grant assistance provides the funds necessary for comparatively small-scale projects that directly benefit residents at the grassroots level with the objective of socio-economic development in developing countries, taking into account the philosophy of human security (as a general rule the limit of provision amount is ¥10 million or less). The organizations eligible for this grant assistance are nonprofit organizations such as the NGOs active in developing countries (locals NGOs and international NGOs; however, organizations covered by Grant Assistance for Japanese NGO Projects are excluded), local public entities, educational institutions, and medical institutions. Projects in partnership with the companies and local governments of Japan are also actively recommended.

- * Public-Private Partnership (PPP) using ODA

- PPP is a form of public-private cooperation in which governmental ODA projects are conducted in collaboration with private investment projects. Input from private companies is incorporated from the stage of ODA project formation. For example, roles are divided between the public and private sectors so that basic infrastructure is covered with ODA, while investment and operation/maintenance are conducted by the private sector. The technologies, knowledge, experience, and funds of the private sector are then used in an effort to implement more efficient and effective projects as well as to improve development efficiency. (Areas for PPP: Water and sewerage systems, airport construction, motorways, railways, etc.)

- * Inclusive business

- Inclusive business is a generic term for a business model advocated by the United Nations and the World Bank Group as an effective way to achieve inclusive market growth and development. It includes sustainable BOP businesses that resolve social challenges.

- * Feasibility survey

- Feasibility survey verifies whether a proposed project is viable for execution (realization), and plans and formulates a project that is most appropriate for implementation. The survey investigates a project’s potential, its appropriateness, and its investment effects.

- * Private-Sector Partnership Volunteer System

- The Private-Sector Partnership Volunteer System is a system in which employees of SMEs and other entities are dispatched to developing countries as Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers (JOCV) or Senior Volunteers (SV), and contribute to the development of global human resources of SMEs and other entities along with their overseas business expansion. The country of dispatch, occupation type, and duration of dispatch are determined through consultation based on the requests from companies and other entities. Volunteers are dispatched to countries in which their companies are considering business expansion. It is expected that the volunteers gain an understanding of the culture, commercial practices, and the technical level of their respective destination countries through their volunteering activities. They are also expected to acquire not only language skills but also communication skills, problem solving skills and negotiation skills, which will be brought back into corporate activities upon their return.

- * Private-Sector Investment Finance (PSIF)

- PSIF refers to one of JICA’s loan aid schemes, which provides necessary investment and financing to private sector corporations and other entities, which are responsible for implementing projects in developing countries. The projects of private companies and other entities in developing countries create employment and lead to the revitalization of the economy, but it is difficult to obtain sufficient financing from existing financial institutions in some cases, due to a variety of risks involved and the unlikelihood of high gains. PSIF supports the development of developing countries by providing investment and financing for businesses which are difficult to sustain by financing from private financial institutions alone but are highly effective for development. The fields eligible for this assistance are: (i) infrastructure development and growth acceleration; (ii) SDGs and poverty reduction; and (iii) measures against climate change.

- Note 3: This is an engineering method that does not cause a power cut when power distribution line maintenance work is being done.

- Note 4: This is a mechanism under which Japan concludes international agreements for Japan’s ODA loans in advance with developing countries that are potentially affected by natural disasters that occur in the future, enabling a swift lending of funds for recovery if a disaster does occur.

- Note 5: An EBF loan is provided for the equity investment made by the government of a developing country in the Special Purpose Company (SPC), the entity responsible for the public work project in the developing country, if a Japanese company is among the implementers of a PPP infrastructure project in which the government of a developing country, state enterprise, or other parties have a stake.

- Note 6: A VGF loan is provided to help finance the VGF that the developing country provides to the SPC, in order to secure the profitability expected by the SPC, if a Japanese company has a stake in a PPP infrastructure project implemented by the government of a developing country.

- Note 7: CCEF-PPP refers to loans that are provided based on the requests from SPCs to perform guarantee obligations, in order to encourage the government of a developing country to develop and utilize schemes that ensure the execution of off-take agreements, and thereby, promote PPP infrastructure development pursuant to appropriate risk sharing between the public and private sectors.

- Note 8: The pillars of the content of the Partnership for Quality Infrastructure are (i) Expansion and acceleration of assistance through the full mobilization of Japan’s economic cooperation tools, (ii) Collaboration between Japan and ADB, (iii) Expansion of the supply of funding for projects with relatively high risk profiles by such means as the enhancement of the function of JBIC, and (iv) Promoting “Quality Infrastructure Investment” as an international standard.

- Note 9: The Expanded Partnership for Quality Infrastructure was announced by Prime Minister Abe at the G7 Ise-Shima Summit in May 2016. It incorporates the provision of financing of approximately $200 billion by Japan-wide efforts as the target for the next five years to infrastructure projects across the world, including Asia, at the same time aiming for further improvement of measures, and strengthening the institutional capacity and financial grounds of Japan’s relevant organizations, including JICA.

(2) Partnership with Universities and Local Governments

Japan utilizes the practical experience and expertise accumulated by universities as well as local governments to implement more effective ODA.

A. Collaboration with universities

A trainee from Myanmar (seated) researches in the doctoral course of Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry & Pharmaceutical Sciences Department of Pharmacology of Okayama University as part of the “Project for Enhancement of Medical Education.” (Photo: Okayama University)

Some of the roles of universities are: to contribute to the development of developing countries; to develop human resources that will be responsible for international cooperation; and to sort out and disseminate the philosophy and theory of Japan’s assistance. Taking these roles into account, Japan is promoting civil participation projects, including technical cooperation, ODA loan projects and JICA Partnership Program (JPP), jointly with various universities with the aim of broad intellectual cooperation regarding all aspects of the cycle of assistance, from sorting out the theory of the assistance to putting it into practice and returning education to the Japanese people.

For example, with the objective of developing advanced human resources who will be the core of socio-economic development in developing countries, Japan is utilizing the JICA Project for Human Resource Development Scholarship (JDS) to accept young officials, etc. from developing countries as students studying abroad in a cumulative total of 33 universities, and 241 students were newly accepted in FY2015.

Furthermore, under an initiative for the development of African industrial human resources through industryacademia- government cooperation (ABE initiative), 148 departments in 71 universities throughout Japan are accepting trainees. Moreover, Japan will launch the Innovative Asia Initiative to encourage innovation in both Japan and Asia by accepting 1,000 competent students from Asia into Japanese universities, etc. to enhance the circulation of advanced and skilled human resources in these areas.

These kinds of cooperation contribute to the development of developing countries and also to the internationalization of Japanese universities.

B. Collaboration with local governments

Members of the Fukuoka City Waterworks Bureau instruct members of Fiji Water & Sewage on leakage survey techniques in Nadi/Lautoka region in the west of Fiji. (Photo: Kensuke Onoe / Fukuoka City Waterworks Bureau)

The various kinds of know-how possessed by the local governments of Japan are necessary for the development of the economies and societies of many developing countries throughout the world. For example, in recent years the growth and urbanization of developing countries has been remarkable, but on the other hand responses to environmental issues and infrastructure issues are not keeping up with the pace of growth; therefore it is considered that the cooperation of the local governments of Japan, which have accumulated rich expertise in the fields of water, energy, waste disposal, and disaster risk reduction, etc., is becoming more necessary and for this reason Japan has promoted the participation of local governments in ODA. Furthermore, from the viewpoint of the needs of the local governments, Japan is actively promoting the overseas expansion of local governments in order to encourage the revitalization and globalization of the local regions of Japan.

In FY2016 Seminars on Collaboration between Local Governments were held 15 times with the objectives of enhancing the potential of the local governments, etc. which will participate in development and international cooperation in developing countries, and thereby revitalizing the regions through internationalization, promotion of industry, etc., by sharing the experience, know-how, networks, etc. of local governments that have overseas expansion experience with other local governments and local companies including SMEs, and deepening their collaboration. In FY2017 Japan is further promoting overseas expansion by holding many more seminars to teach many officials from local governments about the appeal of implementing projects overseas and know-how in the field.

In July 2015 a framework under which JICA accepts proposals for grant aid projects as needed from local governments and the local governments participate in the grant aid projects was established. The achievements under this framework in FY2015 include the approval of projects by Kitakyushu City (1 project), and Yokohama City (2 projects). In April 2016 Japan established Grant Assistance for Grass-Roots Human Security Projects in collaboration with local governments and set preferred slots for actively adopting projects that encourage the local governments of Japan to collaborate with local NGOs, local public entities, etc. and since then it has been actively supporting matching.

Through these various efforts Japan is further encouraging collaboration with local governments.

•The Philippines

Expansion of Participatory Local Social Development Based on IIDA Local Governance Model in Legazpi City, Philippines

JICA Partnership Program (local government type) (July 2013 – July 2016)

A project manager instructs local workers and Technical Working Group (TWG) of the Bicol University on “Identifying Issues by Residents.” (Photo: Toshiharu Sato / JICA)

At Legazpi City in the Philippines, initiatives for Participatory Local Social Development (PLSD) were being carried out by both the government and the residents, but they have not yet been expanded to the whole region because of insufficient knowhow and experience. Therefore, this project was commenced with the objective of transmitting the advantages of Iida city in Nagano prefecture such as the urban development with the focus on the independence and uniqueness of the region that it has traditionally tackled, and Iida city’s experience and knowhow of resident participation and governance to Legazpi City in the Philippines, and putting them to good use there.

The project started with ensuring drinking water as an important theme for Legazpi City. The residents participated independently in the work such as digging wells and constructing simple waterworks and in a series of activities including making the water supply facilities a shared asset of the village as well as carrying out maintenance and water fee collection by themselves. In addition to the local residents, the Legazpi City administrative authorities, NGOs, the local Bicol University and leaders of the residents also proactively participated and cooperated. These initiatives and effects have gained the trust of the locals and have produced major outcomes. For example, the Legazpi City council approved the incorporation of participation-type development techniques in the development plans of all of the barangays (the smallest administrative unit) of the city.

Based on these experiences, this project constructed the first community hall in the Philippines and further resident participation-type governance is proceeding centered on the community hall. The Taysan Resettlement Site Community Hall built in the Taysan resettlement site is managed and operated on a daily basis by the resident organization itself, and a variety of community activities such as regular meetings of board members of community associations, general meetings of the resident organization, a range of training sessions and seminars, regular medical examinations, feeding projects, backyard vegetable gardening and group cleaning campaigns are vigorously carried out at the community hall.

These initiatives not only revitalized the local area, but also presented an opportunity for the people of Iida City to gain renewed awareness of the value of the community halls they possess and the original approach to resident participation and governance. Now the initiatives have led to the revitalization of Iida City as well. In particular, the municipal employees, community hall employees, and leaders of the region have renewed their studies of participation-type development. It is expected that these kinds of initiatives will become a new model of international cooperation under which both the Philippines and Japan are revitalized.

(3) Partnership with Civil Society

In today’s international community, a wide range of actors, including private companies, local governments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are playing a bigger role in finding solutions to development challenges and achieving quality growth in developing countries. In this regard, collaboration with civil society centered around NGOs is essential from the viewpoint of deepening public understanding and participation in development cooperation, and further expanding and strengthening social foundations underpinning such cooperation.

A. Direct participation in assistance to developing countries through the Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers (JOCV) and Senior Volunteers (SV)

A Senior Volunteer, Ms. Haruko Asatsuke, teaches Japanese language at a high-school in Belgrade, Serbia. Many students are interested in Japanese pop culture, anime and fashion, and are eager to learn Japanese. (Photo: Shinichi Kuno / JICA)

Founded in 1965 and marking its 50th anniversary in 2015, the Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers (JOCV) program has dispatched approximately 40,000 people to 88 countries in total, contributing to the development of developing countries as an example of “Visible Japanese Assistance.” The JOCV program is a participatory program in which young and skilled Japanese people aged 20 to 39 are dispatched to developing countries in principle for a two-year-term to assist socio-economic development in those countries, while living and working as volunteers with local residents.

The Senior Volunteers (SV) program is also a participatory program in which Japanese men and women aged 40 to 69 who have a wide range of skills and abundant experience engage in development activities for developing countries. The SV program is considered as the senior version of the JOCV program.

These volunteer programs contribute not only to the socio-economic development of the relevant countries, but also to deepening their people’s affinity for Japan, and thereby increasing mutual understanding and friendships between Japan and these countries. Additionally, in recent years, the programs have drawn attention in the aspect that volunteers’ experience is given back to society. For example, upon returning to Japan, volunteers contribute their services to Japanese private companies for the expansion of their businesses in developing countries.

In order to promote these initiatives, the Government of Japan is making it easier for people to take up positions in these volunteer programs by offering career support to those who have returned to Japan, along with enhancing public communication work to inform people of such possibilities as taking advantage of career breaks.*

- * Volunteer system taking advantage of career breaks

- Professionals working at companies, national or local governments, or schools are participating in the JOCV program and SV program by taking advantage of such arrangements as career breaks with a waiver of duty of devotion to service, thereby remaining affiliated with their organizations.

B. Assistance to NGOs and participation in NGO activities

Japanese NGOs implement high-quality development cooperation activities in various fields including education, medical care and health, rural development, refugee assistance, and technical guidance on landmine and unexploded ordnance (UXO) clearance in developing countries and regions. They also provide prompt and effective emergency humanitarian assistance in sites affected by conflict or natural disasters such as earthquake and typhoon. In this way, Japanese NGOs are attuned to different local situations in developing countries and are able to carefully tailor responses to the assistance needs of the local people. Thus, Japanese NGOs can provide assistance at the grass-roots level, reaching out to local needs that are difficult to address through assistance by governments and international organizations. Furthermore, MOFA regards Japanese NGOs that embody “Visible Japanese Assistance” as indispensable players in development cooperation, and therefore, attaches importance to collaborating with NGOs. Specifically, MOFA implements: (i) financial support for the development cooperation activities of NGOs; (ii) support for the capacity building of NGOs; and (iii) dialogues with NGOs.

In addition, based on the Development Cooperation Charter, MOFA and NGOs jointly developed a plan outlining the direction of their collaboration over the next five years and announced the plan in June 2015. Subsequently MOFA and NGOs conduct together the follow-up of the plan.

•Ghana

Nutrition Improvement Project for Children under Two Years Old in the East Mamprusi District of the Northern Region

Grant assistance for Japanese NGO projects (February 16, 2016 – )

A partner organization serves as the facilitator of a VSLA Group meeting. (Photo: CARE)

In Ghana while the poverty rate has dropped greatly based on the economic growth in recent years, other issues such as regional disparities have become more noticeable. In particular, the Northern Region faces chronic poverty. The nutritional condition of children under five years old, which is linked to the poverty rate, is aggravated in the region. Improvement of the nutritional condition of the children is not only a current urgent issue, but also early realization of the improvement is required from the perspective of the prevention of future poverty as well, so that the children can lead healthy and productive lives in the future.

With a view to solving these issues, Japanese NGO CARE International Japan collaborated with Ajinomoto Co., Inc. to develop a public-private sector collaboration project in 13 villages. The project aims to improve the nutrition of infants by utilizing the nutritional supplement KOKO Plus developed by Ajinomoto Co., Inc. Moreover, efforts have been made to expand the outcomes of the project to another 60 villages.

There are two main kinds of activities. Firstly, workshops in which the participants can learn from each other about maternal and child health and nutrition, and cooking lessons using local ingredients are held so that the guardians of the infants can acquire knowledge about nutrition and health and practice appropriate dietary habits. Secondly, the project is also focusing on the development of female entrepreneurs. Female entrepreneurs will handle activities to spread knowledge of nutrition and the sales of KOKO Plus, which means the women can earn income by themselves, leading to their independence.

As a part of the support for women to set up businesses, this project launched village savings associations to handle small savings and loans in villages which have no financial institutions. As of September 2016, 157 groups have been launched, and currently training in operational methods is being provided while savings and loans have already started. Generally the residents of farming villages in Ghana are running independent businesses, so the project also plans to train female entrepreneurs for these associations in future.

This initiative plays a role in public-private sector collaboration while aiming to realize a cycle in which the guardians of infants can give breast milk and meals to their children appropriately, can support their household budgets with their own businesses in order to do so, and can support the nutrition of their babies using KOKO Plus.(As of September 2016)

C. Financial cooperation for NGO projects

The Government of Japan cooperates in a variety of ways to enable Japanese NGOs to smoothly and effectively implement development cooperation projects and emergency humanitarian assistance projects in developing countries and regions.

| Grant Assistance for Japanese NGO Projects

MOFA provides financial support for the socioeconomic development projects that Japanese NGOs implement in developing countries through the Grant Assistance for Japanese NGO Project scheme. In FY2015, 56 organizations have utilized this framework to implement 108 projects amounting to ¥4.1 billion in total in 35 countries and regions in such fields as medical care and health, education and human resources development, vocational training, rural development, water resource development, and human resources development for landmine and UXO clearance. In addition, as of October 2016, 46 NGOs are members of Japan Platform (JPF), an emergency humanitarian aid organization established in 2000 through a partnership among NGOs, the government, and the business community. JPF utilizes ODA funds contributed by MOFA as well as donations from companies and citizens to carry out emergency humanitarian assistance, including distribution of living supplies and livelihood recovery, for example, when a major natural disaster occurs or a vast number of refugees flee due to conflicts. In FY2015, 90 projects of 12 programs were implemented, including assistance to victims of the earthquake in Nepal in 2015, assistance to refugees and IDPs in Iraq and Syria, assistance for the humanitarian crisis in Yemen, emergency assistance in South Sudan, assistance to victims of the earthquakes in Afghanistan and Pakistan, assistance to victims of the flooding in Myanmar in 2015, and humanitarian assistance in Gaza, Palestine.

| NGO Project Subsidies

MOFA provides subsidies to Japanese NGOs that conduct studies for project formulation, implement postproject evaluations, hold seminars and workshops in and outside of Japan, and implement other activities related to socio-economic development projects. The subsidies have a ceiling of ¥2 million and also up to half of the total project cost. In 2016, 13 organizations utilized these subsidies to implement activities, such as project formulation studies, ex-post evaluations, and seminars and workshops both in and outside of Japan.

| JICA Partnership Program and other JICA activities

In some cases, JICA’s technical cooperation projects are outsourced to the private sector, including Japanese NGOs, so as to make use of the expertise and experience of NGOs, universities, local governments, and a variety of other organizations. Furthermore, as part of its ODA activities, JICA conducts the JICA Partnership Program (JPP)* in which JICA entrusts projects that are proposed by Japanese NGOs, universities, local governments etc. and are related to cooperation activities that directly assist local residents in developing countries. In FY2015, a total of 246 projects were implemented in 50 countries in the world. (Note: Projects implemented in FY2015 for all assistance schemes.)

•Honduras

Project for Improvement of Primary Health Care with Emphasis on Maternal and Child Health in the Municipalities of Texiguat, Vado Ancho and Yauyupe in the South of the El Paraiso Department

JICA Partnership Program (JPP) (partner type) (August 2014 – )

Operational volunteers in front of medicine shelves at a community pharmacy (Photo: AMDA Multisectoral & Integrated Development Services)

Honduras is one of the poorest countries in Latin America and 64.5% of its people are obliged to live in a state of poverty. The indicators regarding maternal and child health are also in a worse situation than the average in the surrounding countries, with the mortality rate of children under five at 22.2 per 1,000 live births, and the maternal mortality rate at 120 per 100,000 live births. With a view to improving this situation, the Honduran Ministry of Health created the Nacional Plan of Health 2021 aimed at achieving its goals in the health area, and it emphasizes primary healthcare carried out through family and community-based plans and actions.

Three municipalities in the south of the El Paraiso Department (Texiguat municipality, Vado Ancho municipality, and Yauyupe municipality) are covered by this project. Approximately 13,000 people live in 52 villages. Among them are many villages where the people have to travel for one or two hours by car or more than four hours on foot to reach the nearest health center with doctors and nurses, so these are the isolated regions that health services are least likely to reach. For that reason, in response to the request of the Regional Health Office of El Paraiso, AMDA Multisectoral & Integrated Development Services HQ (Okayama City), an NGO began a health project targeted at the community level through the JPP.

While the Government of Honduras encourages women to give birth at appropriate places such as hospitals and maternal and child health centers, nearly half of all the births are still carried out at home in the region covered by this project. In order to improve this situation, the project carried out activities to make expectant and nursing mothers in the region aware of the importance of giving birth in medical facilities, by training the traditional midwives and health volunteers in the villages and improving the capability of the health center staff responsible for prenatal and postnatal medical examinations. Furthermore, the local governments and residents cooperated to put in place mechanisms for solving the health problems of the region, through the establishment of sustainably-operated community pharmacies by volunteers, and by organizing emergency transportation committees for transporting pregnant women to hospital when they are in a dangerous condition.

As a result of advancing these activities, in a little less than two years since the project started the consultation rate for prenatal and postnatal medical examinations in the six health centers in the project had increased by more than 30% and the number of births in medical facilities had also increased by 60%. The community pharmacies and emergency transportation committees established in all 12 villages in the project region are also being operated by the residents selfreliantly, leading to improved primary healthcare for mothers and children in the region covered by the project.

It is expected that this maternal and child health model based on the support of Japan will be disseminated by the local health administration to other regions facing similar problems. (As of August 2016)

D. Establishing a better environment for NGO activities

Further measures to support Japanese NGO activities other than financial assistance include programs for establishing a better environment for NGO activities. The objective of these programs is to further strengthen the organizational arrangements and project implementation capabilities of Japanese NGOs, as well as develop their human resources. Specifically, MOFA carries out the following four programs.

| NGO Consultant Scheme

Under this scheme, MOFA commissions highly experienced NGOs in Japan (16 organizations were commissioned in FY2015) to address inquiries and respond to requests for consultation from the public and NGO workers, regarding topics such as international cooperation activities, ways of NGO organizational management, and methods for providing development education. NGO consultants also make themselves available for free lectures and seminars of international cooperation events and other educational events providing opportunities for many people to deepen their understanding of NGOs and international cooperation activities.

| NGO Intern Program

The NGO Intern Program aims at opening up the door for young people seeking employment with international cooperation NGOs in Japan and to train them for their contribution to Japan’s ODA in the future. Through this program, MOFA seeks to expand the international cooperation efforts of Japanese NGOs and further strengthen the collaborative relations between ODA and NGOs. To this end, MOFA commissions international cooperation NGOs in Japan to accept and train interns and pays for a certain amount of the training costs.

The NGOs that accept interns may apply to extend the length of the internship of “new interns” hired for 10 months by another 12 months as “continuing interns” for a maximum of 22 months of intern training. In FY2015, 18 interns were newly accepted into NGOs through this program.

| NGO Overseas Study Program

The NGO Overseas Study Program covers the costs of the overseas training of mid-career personnel from Japan’s international cooperation NGOs for a period of one to around six months, aimed at strengthening their organization through developing human resources. The training is divided into two types: Practical Training, through which participants will gain working experience at overseas NGOs or international organizations that have an excellent track record in implementing international development programs and giving relevant policy recommendations, in order to build up the personnel’s practical capabilities; and Training Enrollment, through which participants will take fee-based programs offered by overseas training institutions, in order to deepen the personnel’s expertise. Trainees can establish training themes flexibly based on the issues that their organizations are facing. Upon returning to Japan, trainees are expected to return the fruits of their training to their organizations by contributing to their activities, as well as to a wide range of other Japanese NGOs, by sharing information and enhancing the capabilities of Japanese NGOs as a whole. In FY2015, 16 people received training through this program.

| NGO Study Group and NGO Support Project

MOFA supports Japanese NGOs in organizing study group meetings to build up the capabilities and expertise of NGOs. Specifically, NGOs which are commissioned to implement the program conduct studies, seminars, workshops, and symposiums in cooperation with other NGOs as appropriate. This program is designed so that NGOs themselves strengthen their organizations and capacities by accumulating experience through the above activities and reporting or suggesting improvement policy in detail. In FY2015, study groups were organized on five themes: “Towards TICAD VI: African Development and the Role of NGOs”; “Evaluation Capacity of NGOs: How should the Organizations and Projects of NGOs be Evaluated?”; “Strengthening the Capabilities of Local NGOs in International Cooperation Activities: Including Measures to Strengthen the NGO Consultant Scheme of MOFA to Support Local NGOs”; “Support for Socially Vulnerable Children and Young People with Disabilities in International Cooperation and the Role of NGOs”; and “Survey on the Advantages of NGOs in the Bequest Donation Market.” Activity reports and outcomes are available on the ODA website of MOFA.

In addition to MOFA’s supports, JICA also provides a variety of training programs for NGO members, which include the following:

(i) Basic seminar on project management utilizing the PCM method for individuals in charge of international cooperation

Equips NGO personnel with approaches for planning, designing, and evaluating projects in developing countries using PCM;*

(ii) NGO human resources training and Regional

NGO-Proposed training (Currently Training for organizational strengthening of NGOs by regional NGOs);

(iii) Dispatch of domestic advisors for NGO organizational strengthening

Dispatches advisors with knowledge and experience relevant to domestic public relations activities, funds procurement, and accounting in order to strengthen NGOs’ abilities in these fields; and,

(iv) Dispatch of overseas advisors for NGO organizational strengthening

Dispatches advisors to give guidance on strengthening the necessary capabilities for effective implementation of overseas projects.

E. Dialogue with NGOs

| NGO-Ministry of Foreign Affairs Regular Consultation Meetings

To promote a stronger partnership and dialogue between NGOs and MOFA, the meeting was launched in FY1996 as a forum for sharing information on ODA and regularly exchanging opinions on measures for improving partnerships with NGOs. Currently, in addition to the General Meeting held once a year, there are two subcommittees which are the ODA Policy Council and the Partnership Promotion Committee. In principle, both subcommittees are convened three times a year, respectively. At the ODA Policy Council, opinions are exchanged on general ODA policies, while at the Partnership Promotion Committee, the agendas focus on support for NGOs and partnership policies.

| NGO-Embassies ODA Consultation Meeting

Since 2002, the NGO-Embassies ODA Consultation Meetings have been held to exchange ideas and opinions with Japanese NGOs that work in developing countries. The meetings are held to exchange views on the efficient and effective implementation of ODA among NGOs and other actors.

| NGO-JICA Consultation Meeting, NGO-JICA Japan Desk

Based on equal partnership with the NGOs, JICA holds the NGO-JICA Dialogue Meeting to promote the realization of more effective international cooperation, as well as public understanding towards and participation in international cooperation. JICA has also established NGOJICA Japan Desks in 20 countries outside of Japan in order to support the field activities of Japanese NGOs and to strengthen projects conducted jointly by NGOs and JICA.

- * JICA Partnership Program (JPP)

- JPP is a part of the ODA programs in which JICA supports and jointly implements international cooperation activities for local residents in developing countries with Japanese NGOs, universities, local governments, and organizations such as public interest corporations. JPP has three types of schemes depending on the type as well as the size of the organization: (i) Partner Type (Main target: Project amount not exceeding ¥100 million and to be implemented within five years); (ii) Support Type (Project amount not exceeding ¥10 million and to be implemented within three years); and (iii) Local Government Type (Project amount not exceeding ¥30 million and to be implemented within three years).

- * Project cycle management (PCM) approach

- PCM approach is a participatory development method of utilizing a project overview chart to manage the operation of the cycle of analysis, planning, implementation, and evaluation of a development cooperation project, which consists of participatory planning, monitoring, and evaluation. This method is used by JICA and international organizations at the site of development cooperation.

(4) Partnership with International and Regional Organizations

A. The need for partnership with international organizations

The global challenges of recent years that transcend national borders and cannot be dealt with by a single country alone, such as poverty, climate change, disaster risk reduction, and health, require the unified effort of the international community as a whole. In this regard, collaborating with international organizations that have broad networks including in dangerous regions and a high level of expertise, is critically important for realizing Japan’s policy goals based on the principle of Proactive Contribution to Peace.

The year of 2015, which saw the deadline of the MDGs, the adoption of the 2030 Agenda to replace the MDGs, the establishment of a post-2020 framework on climate change, and the holding of the Third UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction in Sendai, was a pivotal year for UN diplomacy. Against this backdrop, it is an important endeavor to further strengthen collaboration with international organizations, in order for Japan to steer international rulemaking efforts.

The Japanese government also collaborates with a variety of other Japanese actors, including Japanese companies and NGOs, to implement assistance through international organizations.

| Concrete collaborative projects with international organizations

In 2015 and 2016, Japan proactively contributed to addressing global issues in cooperation with international organizations including UNDP and UNICEF.

For example, Japan provided ¥4.453 billion (provisional figure) in grant aid for the “Project for Infectious Diseases Prevention for Children” in Afghanistan through UNICEF. The project provided polio vaccines, periodic BCG vaccinations, and periodic measles vaccinations and promoted public awareness of the importance of vaccination. Furthermore, Japan provides development assistance through UNDP in a variety of fields including poverty reduction, disaster risk reduction, gender, and improvement of governance primarily in the Middle East and Africa but also in other countries around the world.

| Examples of policy coordination with international organizations

In the process of drafting the 2030 Agenda, Japan worked closely with the international community including UNDP, which served as the coordinator within the UN, to lead the discussions towards the formulation of the new international development goals.

In August 2016, UNDP took the opportunity of TICAD VI to hold the Global Launch of the Africa Human Development Report 2016 in Nairobi, Kenya. Minister for Foreign Affairs Fumio Kishida who attended the event stated that Japan would collaborate with the international community, in particular UNDP, to further promote development of Africa and the empowerment of women in order to work towards gender equality and the acceleration of women’s empowerment in Africa, the themes of the report.

In June 2016 Japan returned to the OECD Development Centre. (Note 10) The Centre is a think tank in the OECD that carries out surveys and research regarding the development issues of developing countries. Not only the OECD member states but also emerging countries and developing countries that are not members of the OECD participate in the Centre. It plays an important role as a forum for policy dialogue on development in a variety of regions. Japan intends to actively cooperate with and take part in the Centre’s activities, play a role in further strengthening relations between the Centre and Asia, and support the activities of the Centre including contributing to the implementation of the 2030 Agenda. In December the same year, the international seminar “Global Development Trends and Challenges Emerging in Asia: Making the most of the OECD Development Centre” was co-organized by the Development Centre and MOFA. This seminar was the first major joint event since Japan’s return to the Development Centre. Discussions were held on the efforts of the Development Centre, the necessity of strengthening relations between Asia and the OECD, the role that Japan should play, etc. It was an important step in further strengthening relations between the OECD and Asia going forward.

B. Examples of partnership with regional organizations

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has recognized the strengthening of intra-regional connectivity as the most important priority and has built the ASEAN Community consisting of the Political-Security Community, Economic Community and Socio-Cultural Community at the end of 2015. Japan has supported ASEAN’s efforts to strengthen connectivity by making use of Japan’s experience with infrastructure development and improving the investment environment, with the viewpoint that turning a more integrated ASEAN into a hub for regional cooperation is essential for the region’s stability and prosperity.

Building the ASEAN Community and the subsequent integration efforts require even greater efforts for the resolution of remaining issues, including strengthening intra-regional connectivity and narrowing development gaps. Japan continues to advance proactive cooperation for the integration of ASEAN, while deepening the bonds of trust and friendship between Japan and ASEAN.

C. Partnership with other donors

Japan coordinates its development cooperation with that of other donors. In 2016, Japan held dialogues on development cooperation with the United States, the Republic of Korea and Australia. Amid the decreasing trend of the overall ODA budget of major donors, it is becoming increasingly important to cooperate and collaborate with international organizations and other donors to effectively utilize the limited ODA budget of each country for the development of developing countries and to address development issues by the international community as a whole.

In recent years, Japan and the United States have further strengthened their cooperation and collaboration. The “Fact Sheet on United States-Japan Global Cooperation,” which was unveiled during then U.S. Vice President Joseph Biden’s visit to Japan in December 2013, highlighted development assistance and contributions to global security. Furthermore, based on this Fact Sheet the newly established senior-level Japan-U.S. Development Dialogue is regularly being held. In March 2016 the two countries held the Third Japan-U.S. Development Dialogue, and discussed a wide range of development issues including the SDGs, the G7 Ise-Shima Summit, at which Japan served as the chair, TICAD, an expanded role for emerging donors and institutions and responses to other global and regional issues. When then President Barack Obama visited Japan in April 2014, the two countries released the “Fact Sheet: U.S.-Japan Global and Regional Cooperation,” outlining concrete forms of bilateral collaboration in Southeast Asia, Africa, and other regions.

In April 2015, the “Fact Sheet: U.S.-Japan Cooperation for a More Prosperous and Stable World” was issued when Prime Minister Abe visited the United States. This Fact Sheet lays out bilateral collaboration in various fields, such as development cooperation, environment and climate change, empowerment of women and girls, as well as global health.

In this context, Japan and the United States have collaborated on an array of efforts, including assistance for African women entrepreneurs, a UN Women project for realizing safe cities for women and girls in India, financial cooperation for unexploded ordnance (UXO) clearance operations in Laos and for a group supporting women in Papua New Guinea, and seminars for women entrepreneurs and others who play active roles in Cambodia. Japan considers that strengthening such Japan-U.S. development cooperation would widen the scope of bilateral relations, and contribute to the further development of the Japan-U.S. Alliance.

At the G7 Ise-Shima Summit held in May 2016 documents such as the G7 Ise-Shima Economic Initiative were adopted, and the G7 agreed to the promotion of the 2030 Agenda. In addition it produced specific outcomes regarding the promotion of such development cooperation fields as “quality infrastructure investment,” “women,” and “global health.”

Members of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the OECD, the so-called traditional donor countries, have been taking a leading role in carrying out development cooperation in the international community. In recent years, however, emerging donor countries such as China, India, Saudi Arabia, Brazil and Turkey also have had a significant influence on the development issues of developing countries.

This trend also appears within the framework of the G20. Consultation on development issues is now conducted, not only by the developed countries but also by a mixture of countries including emerging and developing countries. Japan facilitates discussions by encouraging the participation of emerging donor countries in various meetings to assist the alignment of their development cooperation with other international efforts.

Japan, with an experience in transitioning from an aid recipient to a leading donor, works with countries including emerging countries to promote triangular cooperation that incorporates South-South cooperation.*

D. Proactive contribution to international discussions

Advances in globalization have rapidly increased the extent to which countries in the world influence and depend on one another. There are many threats and issues that are not problems of a single country alone but concern the whole international community and require concerted efforts, such as poverty, conflict, infectious diseases, and environmental problems.

In particular, 2015 was a year in which important international meetings were held, notably, the UN Summit that adopted the international development goals through 2030, i.e., the 2030 Agenda (September, New York), as well as COP 21 that adopted the new international framework on climate change for 2020 and beyond, i.e., the Paris Agreement (November-December, Paris), and the Third UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction that adopted the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, an international framework for disaster risk reduction until 2030 (March, Sendai). As such, 2015 was a key milestone year for the international community’s response to global issues.

Even before the international community’s discussions went into full swing, to work towards the adoption of the 2030 Agenda, Japan played a leading role in establishing a truly effective new agenda by hosting the MDGs Follow-up Meeting, organizing informal policy dialogues, holding UN General Assembly side events, and proactively participating in the intergovernmental negotiations since January 2015. Furthermore, hosting the Third UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction in March was an essential contribution to the adoption of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. Japan has contributed to the efforts of a sustainable and resilient international community through these efforts to address global issues.

Meanwhile, the OECD-DAC seeks to increase the quantity of assistance for developing countries and to improve its efficiency, through strengthening collaboration with emerging countries and diversified actors engaged in development, such as emerging countries and the private sector, and through more effective mobilization and utilization of public and private finance. Specifically, discussions are under way to revise measurement methods to ensure the proper assessment of each country’s ODA disbursements, and on ways to statistically capture a range of non-ODA development finance, including private sector investment and financing from emerging donor countries.

In addition, efforts for not only increasing the “quantity” of aid but also enhancing aid effectiveness (“quality”) have been made by the Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation (GPEDC) in order to achieve international development goals such as the SDGs.

The Second High-Level Meeting of GPEDC was held from November 28 to December 1, 2016 in Kenya, with the participation of not only the governments of developed and developing countries but also a variety of organizations and groups involved in development including civil society organizations, the private sector and parliaments. This meeting was the first High-Level Meeting held after the adoption of the 2030 Agenda. Meaningful discussions were held about the effective contribution of development cooperation towards the achievement of the SDGs. In particular, on the grounds that the business community also has a major interest in the outcomes of sustained development, the necessity of further utilizing private sector investment in development was confirmed, and the importance of development of the investment environment, tax system reforms and promotion of public-private collaboration were discussed. Furthermore, regarding triangular cooperation, one of the effective tools for the achievement of the SDGs, Japan explained its approach for effective implementation including cost sharing, and gave a presentation on examples of Japan’s efforts to promote the empowerment of women in Kenya. As a member of the GPEDC Steering Committee since August 2015, Japan contributes to international efforts to improve the effectiveness of development cooperation, building on its experience.

Furthermore, the Sixth Asian Development Forum* was held in March 2016 in Colombo, Sri Lanka, and under the theme of “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Voice from Asia” required national policy changes and enhancement of global partnership for the implementation of 2030 Agenda as well as key issues for inclusive growth in Asia such as infrastructure development and industrial human resources development were discussed from the perspectives of Asian countries in the meeting.

The Second High-Level Meeting of the GPEDC held in Nairobi, Kenya from November 28 to December 1, 2016.

- * South-South cooperation

- South-South cooperation refers to cooperation provided by relatively advanced developing countries to other developing countries, utilizing their experiences in development and their own human resources. In many cases the cooperation, primarily technical cooperation, is conducted in countries that have similar natural environments and cultural and economic circumstances, facing similar development challenges. Support by donors or international organizations for cooperation between developing countries is referred to as “triangular cooperation.”

- * Asian Development Forum

- This forum aims to form and disseminate the “voice of Asia” regarding development cooperation, on the basis of discussions on various development-related issues and future approaches by government officials from Asian countries, representatives of international organizations such as ADB, the World Bank, and UNDP, as well as representatives of private-sector enterprises, among other stakeholders who gather at the forum. It was established under the initiative of Japan and the Republic of Korea, and the first forum was held in 2010. Since then, a group consisting of the organizing countries, as well as past host countries including Japan has been playing a central role in its operation.

- Note 10: Japan joined the OECD Development Centre at the time of the Centre’s founding in 1962 but withdrew in 2000 due to issues such as governance of the Centre. However, based on the improvement that has been seen with the Centre’s governance, as well as the increase in the number of new countries taking part, Japan decided to return to the Centre.