Japan's Official Development Assistance White Paper 2007

Column 1 Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers (JOCV)

The Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers (JOCV) is a national project which supports young men and women with technical skills aged between 20 and 39 in order to cooperate for the social and economic development of the regions through living with the people of developing regions. Since the project's initiation in April 1965, 29,889 volunteers have been dispatched to 81 countries (4,407 volunteers in FY2006 including newly dispatched volunteers and continued ones from previous years) to provide cooperation by working with people of developing countries.

"The Strength of Africa" as Felt in Djibouti

Takehiro Kido

(Occupation: Specialist in Expanding Village Development)

In July 2005, Takehiro Kido was dispatched, as a Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteer, to Djibouti for two years to lead the management of a microfinance* organization. Keeping up his interest in international cooperation, he got a job at a bank after graduating from university. When Kido, who was a sales representative for small and medium-sized companies at that time, encountered the project which matched his own field of specialty, he decided to join it, considering it would lead to the realization of his dream of being involved in development assistance.

Located in the horn of Africa, Djibouti is a young country that in 2007 celebrated the 30th anniversary of its founding. It is a small country with a population of approximately 790,000, and it is said that more than half of them live in poverty. In 1998, the African Development Bank established the Social Development Fund (a microfinance facility) in order to improve the current situation in Djibouti: small loans have been provided to 8,000 women living in poverty. I was assigned to the Social Development Fund in 2005 to provide management support.

Microfinance is provided to individuals who are energetic despite suffering from poverty. There is a tendency for people to possess a negative impression in regard to developing countries. Nevertheless, in these past two years I gained a strong sense of the inherent strength that lies within all humans. The loan recipients I met all spoke encouragingly, saying things such as, "I am going to purchase inventory in Dubai," "I am going to open a new store," or "I think I will open a furniture store next." Despite the women's severe living environments, they have much more zest for life and ideas than we Japanese.

Needless to say, not everything goes so successfully, and it is difficult for microfinance alone to save the poorest in society. Yet I sensed that developed countries would be called on in the future not to simply provide goods, but to believe in the inherent strength of these women and to make efforts to draw out that strength. I feel that my two years in Djibouti taught me that poverty eradication begins with believing in the capabilities of those suffering from poverty, and that providing them with as many opportunities as possible is the most powerful method.

With the objective of expansion, the Social Development Fund is to merge with another organization, but plans to continue the microfinance project within Djibouti. I will continue to believe in the inner strength of the Djiboutian people and look forward to their future success.

Kido (middle) with other staff from the Social Development Fund (Photo: Takehiro Kido)

A storeowner explaining wishes for microfinance (Photo: Takehiro Kido)

I Want to Make Radio Exercises for the Marshall Islands!

Syoko Nakamura

(Occupation: Health Nurse)

After working for four years as a health nurse at the health and safety center of a precision equipment manufacturer, Syoko Nakamura took administrative leave, and was dispatched as a Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteer to the Ministry of Health in Majuro, the capital city of the Marshall Islands, for a two-year period beginning in July 2004. Nakamura has been interested in international cooperation since she was a student. When she happened to notice that overseas cooperation volunteers were being sought for lifestyle-related disease prevention, her field of specialty, she decided to apply without hesitation.

The Pacific island state of the Marshall Islands is made up of 29 atolls, inhabited by fewer than 60,000 people. The main industries are coastal fishing and agriculture, such as cultivating coconuts. However, both of these industries are of small scale and in recent years the nation has relied on imports from the United States for many of its foodstuffs.

Marshall people's diets have changed due to this, as they have begun eating foods such as imported rice, canned tuna, corned beef, and high sugar snacks instead of the traditional breadfruit and pandanus,* which are full of dietary fibers. Moreover, the use of automobiles in the capital has increased and people are more sedentary than in the past. These have been factors in the recent spread of lifestyle-related diseases and the increase in the number of diabetics in the Marshall Islands. Despite living on Pacific islands located more than 4,500 kilometers from Japan, the residents of these islands face the same metabolic syndrome issues as the Japanese.

When conducting an examination on one remote island, I was surprised to find that 98% of those adults examined suffered from obesity and 50% were suspected of having diabetes. These types of lifestyle-related diseases have become a significant issue in the Marshall Islands. Of those diseases, symptoms for diabetes have especially progressed and many people have been subjected to having their legs amputated and having to live life in a wheelchair. I was worried because those who use wheelchairs will naturally exercise too little. However, one day I saw radio exercises being broadcasted for overseas audiences by NHK. In that program there was both a standing and sitting instructor. So I thought that the elderly and people in wheelchairs could participate in this exercises. Then I decided to create a version of radio exercises especially for the Marshall Islands.

Thereupon, I requested the assistance of a cooperation volunteer that had been assigned to direct physical education, also asking local people to review as well, and we decided on poses and moves of the exercises. I had the music created by a local NGO that was conducting health enlightenment activities for youth. Additionally, I wanted the project to be something that would take root in the Marshall Islands for a long time by having local residents actually appear in the pamphlet and video. I made efforts to have a large number of people try out the exercises themselves by creating opportunities for proactively exhibiting the completed exercises to hospital officials, and distributing the video to all elementary schools in the capital.

I felt my limitations and was frustrated as I realized I was only one staff member; however, I believe that it was my position as a cooperation volunteer that allowed me to work together with locals in conducting community-rooted activities. I regretted that I returned to Japan before conducting adequate public relations activities. Nevertheless, I look forward to the video being utilized in the spread of Japanese radio exercises throughout the Marshall Islands, and being of any help to island people to improve their health.

Nakamura explaining the body fat measurement device to local staff at the healthcare center (Photo: Syoko Nakamura)

Introducing Japanese okonomiyaki (Japanese unsweetened pancake) to local people who like sweet pancakes (Photo: Syoko Nakamura)

Using Japan's Traditional Dye "Persimmon Tannin"* in Nepal

Minako Nakayama

(Occupation: Food Processing)

Minako Nakayama worked at a food related company after studying food manufacturing at university. In April 2005, as a Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteer, she was dispatched for a two-year period to Nepal, to direct food processing at the Kirtipur Horticulture Center, located in the southwest of Katmandu Valley. Nakayama decided to participate in the overseas cooperation volunteers as various experiences — including being shocked by the disparity between rich and poor during a trip to India as a student, and considering the meaning of life in the aftermath of the death of her father, who had succumbed to illness — pushed her to want to help other people.

At the Kirtipur Horticulture Center where I was stationed, technical trainings such as seedling production, the breeding of petals of temperate fruit trees including Japanese varieties, and sales are underway through the Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers' project on disseminating horticulture. The Center also made efforts to popularize amagaki persimmons. Furthermore, as there were already many astringent persimmon trees in Nepal's rural areas, efforts were made to spread the use of dried persimmons, and in 2004, the volunteer that preceded me conducted a trial production of persimmon tannin, which is a dye.

However, no means of use for the dye was able to be introduced at that time, and due, also, to its odor, the production of persimmon tannin was unfortunately stopped.

I was assigned to the Center the following year to take over activities and thereupon conducted the second trial production of persimmon tannin. In order not to repeat failures from the previous year, we dyed the net that protected the persimmon orchards from damage by birds with persimmon tannin upon the idea of a project member, whom was also an overseas cooperation volunteer (village development). We also worked to initially raise awareness of the functionality of persimmon tannin, such as for an insect deterrent, waterproofing, and increasing strength, and thereby were able to increase the interest of residents in the dye. Moreover, after conducting a comparison to Japanese varieties I discovered that the Nepalese variety of persimmon is suited for use in dyes as it contains more tannin. This discovery also supported our efforts.

The persimmon tannin created was sent to another overseas cooperation volunteer (dyeing) that advised fair trade groups and producer groups where it was utilized for dyeing thread and fabrics. Then, after a suggestion from an overseas cooperation volunteer (handicrafts) that was stationed at a local NGO Women's Skill Development Project in Pokhara (WSDPP), a prototype bag was created by efforts to add products using persimmon tannin dyes to the dyed plant products (a traditional fabric in Nepal which is woven by using the backstrap loom and applying natural dyes) that had just begun being sold by the WSDPP. I strongly felt that a fusion of techniques from Nepal and Japan had been realized through coordination between overseas cooperation volunteers that went beyond occupation type.

We overcame numerous difficulties such as persimmon tannin going stale in the middle of production, dead mice discovered in the tank, and leaking liquids due to a lack of containers able to withstand the bumpy mountain roads used when transporting the dyes, and the trial production of persimmon tannin dye products is still underway in Nepal today. These efforts have only just begun; however, expectations for persimmon tannin by staff at the Horticulture Center, persimmon farmers, and women at the WSDPP are increasing as they effectively utilize local resources with the aim of creating specialty products that generate a steady cash income.

Nakayama instructing the production of persimmon tannin (Photo: Minako Nakayama)

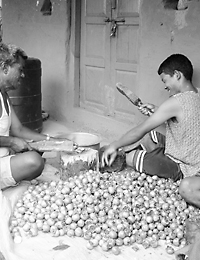

A scene of processing astringent persimmons (Photo: Minako Nakayama)

A woman working on a backstrap loom (Photo: Minako Nakayama)

Next Page

Next Page